A Valley Without Wind Review

Not a fan.

It's the future! Or is it? And an apocalypse has sundered our world, but also time itself. Or has it? And evil overlords plot the world's downfall (again?), but that's OK, because benevolent, talking crystals safeguard humanity. Except humans are extinct. Um.

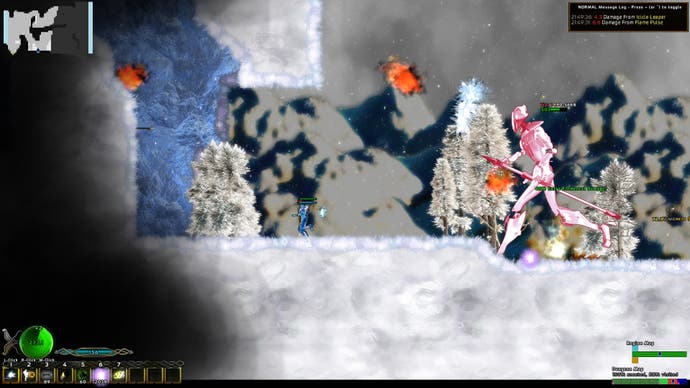

Arcen Games' A Valley Without Wind is a platformer with a randomly generated world, but you'd be forgiven for thinking it had a randomly generated plot, too. The above isn't even the half of it.

Within this scratched CD of a reality you control a "Glyph-bearer", or spell caster, with the (comparatively) simple task of improving your own, private settlement of people. 10 minutes, or an hour, or 10 hours spent with A Valley Without Wind will see you doing the same thing - jogging off into a wilderness of platforms, enemies and missions that has seen no human hand in its creation, and dragging items home to craft new spells, buildings, powers or items that'll propel you back into the world with yet more vigour.

That plot quickly fades into insignificance. The appeal here is in picking your way across a scrapyard of surfaces, plunging into dungeons, dropping rapidly to the lowest room like a ball in a pachinko machine, and emerging with that Brilliant Boulder or Mechanical Macguffin you've had on your shopping list (customisable via the game's "Big Honkin' Encyclopedia") since forever. Using the right spell for the right enemies lends a certain satisfaction, too. Dispatching bats, sea-monsters and robots with swift clicks of the mouse sees their life-force swooping into you, recovering your health with each kill.

If I had to make a comparison in a hurry, I'd say... Terraria slept with Super Metroid, but the baby was so profoundly ugly that they hid it under the stairs, only to spend years listening to it growing madder and larger down in the dark, surviving on a diet of waterlogged back issues of the New Scientist.

The madness of A Valley Without Wind cannot be overstated. Neither can its visual and audible ugliness. You might flee into a rural house to escape a rhino whose sprite is clearly a composite of real-life photography, only to find that inside that tiny house is an endless chamber of floating crates with a couple of air elementals hanging around as if they were waiting for a bus. It's actually the exact kind of surrealist nonsense I'd have liked to surprise me occasionally in Minecraft, but with the unexpected problem that here, it seems dull.

Part of that is down to A Valley Without Wind's unlock system, in which the majority of the game's content is released into the wild once you've shown good behaviour. Kill 100 robots and you'll start encountering a new type of monster. Complete three Boss Tower missions (basically, dungeons that go up rather than down) and Stealth Assassination missions (dark dungeons where you have to locate and murder a boss) appear across the world. Reach level two of a desert dungeon anywhere in the world and a new crafting ingredient, some igneous rock, will begin spawning.

It's bizarre. I've never encountered content drip-feeding that feels this much like an actual drip before. Rather than letting players push forward or laze around as they see fit, you're always peering up at the dispenser and watching each globule of moisture form, becoming disinterested in every single scrap of game design before a new bit plops in.

But mostly, A Valley Without Wind struggles to surprise you because your unique, computer-crafted world feels computer-crafted. The magic of Diablo or Minecraft is that those generation engines are fine-tuned to spew out a world with actual atmosphere. Here, you're exploring platforms, inclines and pits, staircases and lakes, which never snap together in anything resembling a consistent world.

When you encounter a barren labyrinth inside a shed, or a tower with a room that contains a 200-foot-long flue of still water, or a cave full of shortcuts that are too small for you to fit through, it doesn't feel like a mystery, it feels like a glitch: shoddy craftsmanship by your lazy computer. Speaking of craftsmanship, the game's solution for levels which end up being player-unfriendly is to give you a supply of hundreds of wooden platforms and crates your character can spawn en masse like some frightening psychic carpenter. That this, rather than a grappling hook or jetpack, was the developers' solution should give you a hint about the glassy mentality behind the game.

Once you accept, grudgingly, that the enormous world you get to leap your way through isn't particularly interesting, all that's left is for the platforming to hold your attention. Which it does, but without any interest in whether it's doing a decent job, the way paper technically holds most of a Subway sandwich before you ultimately can't tell where the paper ends and the sandwich begins.

There's a strong argument that the most important aspect of a platformer is how your character moves: the minutiae of momentum, weight and feel. Edmund McMillen has said that with Super Meat Boy, they didn't start designing a single level until they had a character who was wonderful fun to send careening around the place. By comparison, your protagonist in A Valley Without Wind trundles about competently, but with no anima, no nuance, no recoil or weight from any of your spells and, most horribly for a game with very vertical levels, no mantling animation. If you leap at a cliff and don't get clean over the lip, you'll rub against the top before sliding back down. What you've got here is low-fat margarine on the cold toast of level design.

The best thing that can be said about the whole package is that, like health-conscious toast, for all my whining there's nothing actively repulsive about A Valley Without Wind. Games that have this much wrong with them tend to take whole days off my life expectancy in the form of raised blood pressure, but I drifted contentedly through this one with the kind of stupefied satisfaction I get from doing the hoovering. Which is sort of what I was doing - hoovering up Upgrade Stones and armour, precious gems and machine parts, then emptying out my bag back in the settlement to shape into more dusty content.

If there is a poignancy to A Valley Without Wind, it's that you really are playing through a post-apocalyptic world, just one that's failed creatively rather than ecologically. The designers were too ambitious, built to high, and you're free to explore what's left.

You're trekking across blasted landscapes that might have been interesting, talking to scattered characters that safeguard the surviving flickers of personality. And slowly but surely, through your hard work, you're unlocking content. Monster by monster, feature by feature, you're reversing the apocalypse, always threatening to summon an interesting game out of the ether. Truthfully, though, that game will never appear. This world is doomed.