A whole new world and exactly the same one: prescient world-building in Only Forward

Silent all these years.

Hello! Welcome to a new semi-regular series (we're aiming to do one a month but who knows right?) in which we'll be looking at world-building, the art of creating interesting settings, and talking to the people who do this stuff for a living.

Games have a rare power to take us to new places, but they share world-building with many other art forms and disciplines. Alongside video games, we're also going to be investigating books and films and architecture and anything else that seems worth exploring.

Today Chris Donlan's been re-reading the gloriously strange novel Only Forward, and talking to its author, Michael Marshall Smith. It's a lovely book, and we're going to try our best not to spoil any of it.

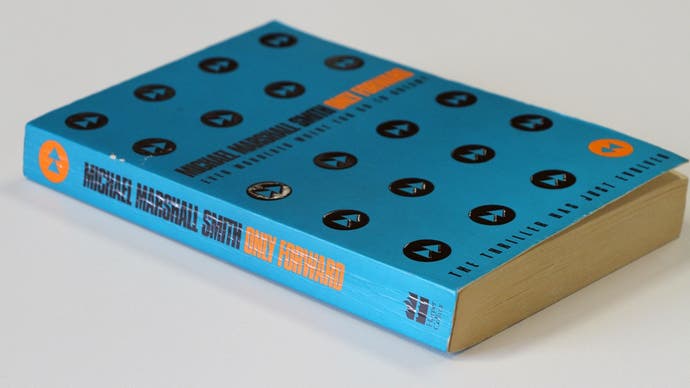

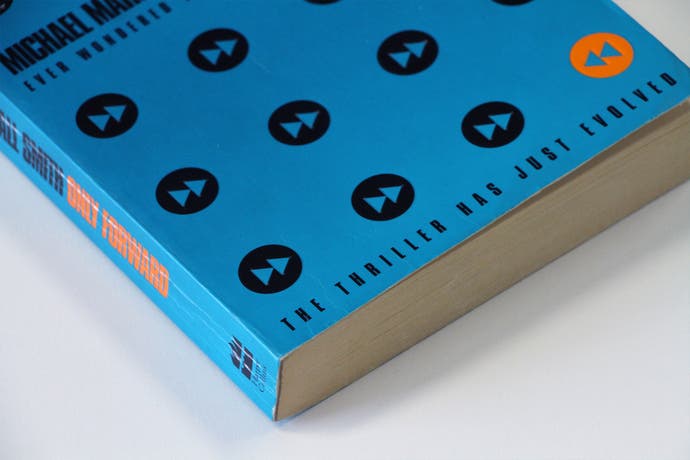

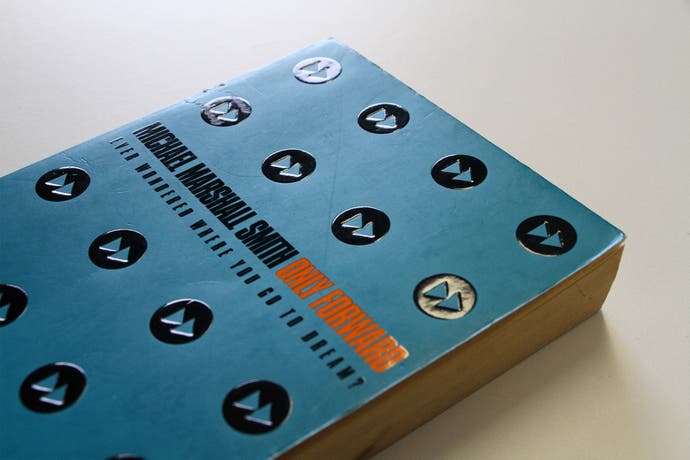

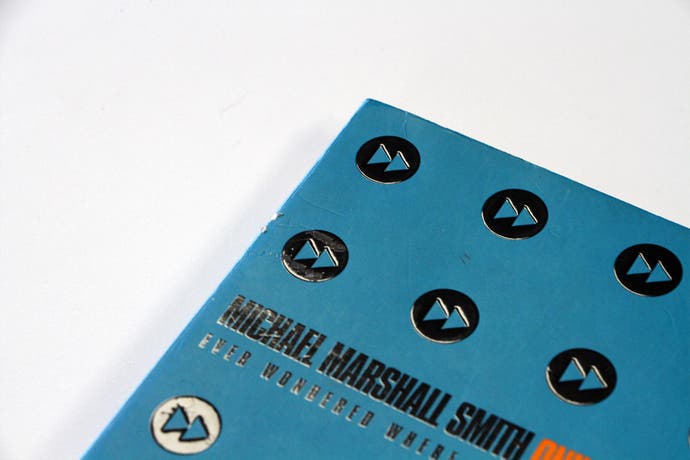

Only Forward, by Michael Marshall Smith

When winter comes around, and Chicago sets its railway tracks on fire, I'm not the kind of person who settles in and starts googling sunny holiday destinations on comparison sites. Instead, I track down a very specific list of strange locations where I might like to live one day, and try to select a new favourite.

What a list! There's Eastedge, down by the sea and very handy for unusual trips. There's NatSci, a place of geeks and lab coats and clean rooms, where everyone is an inventor. There's Red, which some people say is a hellhole and other people argue is just very intense. There's Fnaph, sweet Fpnaph, where everyone believes that the soul is shaped like a Frisbee so they try to bounce about as much as they can and fling themselves into heaven.

I learned about these places in Only Forward, an English science fiction novel from the mid-1990s. Only Forward is set in a place called the City, a metropolis that seems to reach out in every direction and cover an entire country. The City is divided up into neighbourhoods, which work a little like separate states. (It's probably best to think of the whole thing as being analogous to Spain and its system of asymmetrical devolution, in which various communities have differing degrees of autonomy.)

Crucially, Only Forward's neighbourhoods are organised around the interests of their inhabitants. Stark, the novel's protagonist, is a fixer of sorts who lives in Colour, for people who are "heavily into colour," and where the streets colourmatch the locals' clothing. The plot quickly takes him to other neighbourhoods like Sound ("so named because they don't allow any"), Action Centre, which is for people who really like doing things and absolutely have to be busy all the time, so much so that they keep moving the buildings around for no good reason, and Stable, which is so intensely private that it does not allow else anyone in or out.

(Only Forward eventually lures its readers out beyond the City, incidentally, but I'm not going to get into that here, largely because I don't want to rob anyone of one of the most luxurious slow-prickling reveals in any novel I've read.)

Even if Only Forward wasn't an absolute favourite of mine, I would probably still remember it for two things. Firstly, the City is one of those ideas that is so bright and appealing, pitched with such a lovely topsy-turvy logic, that it can't help but escape from the pages of the book and flock and gather in the world around you. I have lived with the City, in the best sense, in the 20 years since I first read Only Forward.

Secondly, the book offered, at the time I first read it, a peculiar kind of freedom. It conjured a sense of the sheer go-anywhere, think-anything potential of fiction so overwhelming and pure that it made the world around me seem brighter and sharper. What a book: not only is the setting so good it invades the reader's own world, it also seems to hint at the untameable power of writing itself. How does it do it?

It turns out that the City arrived almost fully-formed. "I dreamed it," says Smith when we chatted over email in January. "It's a very long time ago now, so I can't remember how much of it came from that one dream, but I do recall waking from sleep with a vision of a compartmentalised world. I'm pretty sure Stable was in the dream, but along with the suggestion of others, too."

At the time he had this dream, Smith was writing horror short stories, and so he didn't immediately think of the City as something he might be able to use for fictional purposes. "But the vision - and the atmosphere - struck with me," he tells me.

Once Smith had decided to turn his dream into a novel, I'm fascinated as to how he started to fill in the rest of the city. Where did the other neighbourhoods come from?

They came from everywhere. "Some were bits of satire on the way the world was then," he explains. "Action Centre for example. Others were just whims. Some were simply me reaching into my head and seeing what came back in my hand."

On this last point, it's not hard to see elements of Smith's own life and preoccupations in Only Forward. He has written extensively about cats in his other books, for example, and so the neighbourhood Cat, which is inhabited purely by cats - they also keep the place nice and tidy - seems particularly personal. Equally striking is Royle, a once-bijou floating town now empty and polluted. A haunting kind of testimony, I presume, to Smith's friend, the writer Nicholas Royle - or Nick "The Bastard" Royle as he is listed in the acknowledgements. Is world-building like this often a kind of veiled self-portraiture?

"I think there's definitely some truth in that," Smith says. "Every creative work is - or should be - personal, and to a degree political. It involves choices - even if they aren't conscious - about what you include, and what you don't: from that comes an inevitable sense of weltanschauung."

The world is becoming more and more like the City every day

Over the years, one of the things Smith's book has started to make me think about is the way that the things people make - even the imaginary worlds hidden in books - still have to travel through time like everything and everyone else. Only forward, I guess. Re-reading the novel in 2019 I'm struck by how much of his wonderfully odd idea now seems prescient. We may not live in communities where the walls change colour or where busybodies are always moving the buildings around when we're not looking (truth told, I'm not one hundred per cent on that last part) but it's hard not to look at the internet and see the City growing quickly online.

So now when I think of the City, I can't help but think of the little rock pools of Reddit, say, with these tightly bundled communities each drawn together by their focus on one enchanted, dazzling thing. One of Smith's earliest stories is More Tomorrow, a horror story of sorts based around bulletin boards and the early internet. Was he thinking of this kind of online phenomenon when he was writing Only Forward?

"Over the years, many people have pointed out to me that a device I describe in the novel sounds remarkably like an iPhone," says Smith. "A very long time before even the forerunners of such objects existed." He considers my question. "No-one's ever observed to me before that the idea of neighbourhoods was also prescient in its way, but I guess you're right... "Rock pools" - that's exactly right. But I've always been aware of the fact that the internet was going to be both a whole new world and exactly the same one. That we'd end up replicating our niches, and possible digging ourselves deeper into them because of the apparent freedom from censure the Internet confers."

Outside of the internet, I wonder if Smith ever sees things in the real world - such as it is - that makes him think of his neighbourhoods? I can't help but be reminded of the Action Centre and their endless hunt for grim efficiency whenever I see someone in the office drinking Huel, for example.

"They're out there, all over the place," he agrees. I don't think he's talking about Huelers (but they are). "Religions, cultures, countries, sub-cultures, the difference between Northern California and Kansas, the people who hate Starbucks and insist on going to the indie coffee shops where they don't roast the beans long enough.

"The world is becoming more and more like the City every day."

Ultimately, I think the thing Only Forward is prodding at - and it's far too skilful to whack you around the face with it - is the dangerous allure of insularity. Some of the city's strangest neighbourhoods show clear signs of people growing more and more isolated, and towards the end of the book, Stark, who has seen more of the city than most, talks about how sad it is that nobody really roams much. Nobody leaves their comfort zone.

Smith mentions this when I ask which neighbourhood he'd want to live in himself. (I've started to fancy Babel, recently, which is a giant tower for people who want to live up high.)

"I think it would have to be Cat," he says. "But the real point of Only Forward's world for me would be the ability to explore, and spend time in all of the neighbourhoods. To revel in the strange and very pleasing zone between reality and virtual."

The drawer book

The real and the virtual! I've been wondering, while re-reading Only Forward this past week or so, just why the book seems to have such a sense of possibilities to it. Why I read it and I get excited about the things fiction can do.

I think the answer is partly to do with the city itself. And I think it's partly to do with trousers.

When we first meet Stark in Only Forward, he's recovering from a hangover. A client calls and after finding his phone - he's been playing around with the gravity inside his apartment, and everything's a bit of a mess - he's summoned to the Action Centre and told to dress appropriately. He runs his clothes through a special device called a CloazVelet (TM), but the CloazValet (TM) is broken, and instead of smartening him up, it turns his trousers "from black to emerald with little turquoise diamonds." On the way to the Action Centre, the colourmatching neighbourhood really struggles with these trousers. "The streets thought about it for a while," Stark explains, "then decided matt black was the ideal compliment for my outfit. Some of the streetlights were picked out in the same turquoise as the diamonds on my trousers too, which I thought was kind of a nice touch." Pages later, Stark gets a lovely message from the computer that runs Colour. It tells him how much it had enjoyed working with his trousers.

It's a tiny thing, but it's one of hundreds of tiny things, all nice comic touches which stop the action for a few seconds just to add to our sense of the world and make it richer. When I first read about the CloazValet (TM), I loved the fact not just that here was a gadget in a sci-fi book that I actually wanted, but here was a gadget in a sci-fi book that was malfunctioning, and in such an interesting way. It makes Stark seem cool and freewheeling for going along with it, cool in a way that feels very real. And it makes the world feel more real. The CloazValet (TM) is just one bit of broken tech, too. The device Stark has been using to mess with the gravity of his apartment dumped everything on the floor when it ran out batteries. That's futuristic and retro. TM.

There are two things I particularly love about this stuff. Firstly, it's writing that itself is very writable. It's hard not to read about the gadgets in Stark's world without thinking of them in your own world, or thinking about other gadgets Stark might know about that we don't. And it's also so lightly done. I was dazzled at the time that Smith was creating a future not out of huge political movements and massive spaceships, not out of asteroid mining and people building shields around the sun. He was building a future out of jokey asides. I was twenty at the time, or thereabouts, just out of university and venturing, on a good day, about as far as the kettle and a box of Asda Red Label tea or whatever it was. I went to the cinema a lot because my friend worked there and could get me in for free. As such, my own world was built out of jokey asides. Suddenly, there was a sense of potency to this stuff, a sense that fiction could be off-the-cuff, detail-ridden, built of things that seemed cheerily throwaway in the best sense.

When I ask Smith about the kind of breezy potential I found in his book - almost as if he was imagining things while he wrote and dropping them in as he went along - he really surprises me.

"Actually," he says, "that's pretty much exactly how it was.

"I am a lamentably freeform novelist to this day," he continues. "I try to plan, and there have been a few books where that's worked well for me. For the most part, however, I tend to start with some characters, a basic underlying idea, a few plot points, a sense of atmosphere, a voice... and that's it.

"'Breezy potential' is exactly how it felt when I began Only Forward. I'd never written a novel before, and I knew (or believed) my first attempt was very likely to remain unpublished. The 'drawer book'. I had a voice in my head - the first-person voice of Stark. I'm not sure where that came from, though to be honest it's not dissimilar to the way I think a lot of the time (or did then: I'm older now). I had the idea of the neighbourhoods.

"And that's... about it. I told myself it didn't really matter as the book would never see the light of day, so I could write whatever the hell I liked and have fun with it. Like a training exercise. I was certainly not expecting that it'd end up being published, at least when I started."

This stuff gives the book a tone which I still feel is very unusual for science fiction, and I've always wondered how much of that was intentional. Stark was wonderfully recognisable to a reader living in England in the 1990s - his jokes and his thought processes were something I could entirely understand. I think that's why the more fantastical elements of the book feel so convincing: it's a light, disarming tone. It's still pretty refreshing. Was it there from the start?

"The voice did just kind of arrive," Smith tells me. "The last book I read before start Only Forward was The Night People, by Jack Finney. Although the voice and tone of that short novel are nothing like Only Forward, I think it probably inspired me to believe that a very direct first-person narrative could work.

"And yes, Stark is very much a man of 1990s England - which is what I myself was at the time. Again, I think this probably a function of my telling myself to have fun, be myself, and give myself no other constraints. I'd read a lot science fiction in my teens but it'd been a long time since I'd looked into the genre. I'd got into horror instead, and a horror writer is what I considered myself at the time. The ideas for Only Forward kept insisting they wanted to be written, however, and so I decided what the hell, go for it. The fact that I was writing into a genre with which I was relatively unfamiliar, and felt no allegiance to, doubtless gave me yet another layer of freedom. I'd previously made a half-hearted start at a horror novel and it wound up sounding like a poor impersonation of Stephen King. Writing SF (or something like it) meant I was heading out into the unknown by myself.

"I didn't know when I was writing that this kind of voice is relatively rare in SF," he admits. "I have since come upon something like it in a few places - the lighter side of Philip K. Dick, Cordwainer Smith, and of course there's Douglas Adams, of whom I was a huge fan in my teens - but it's not something most people try to do. It also ended up with hints of some of my other favourite authors of the time, I guess - Raymond Chandler, PG Wodehouse, Kingsley Amis. A first novel is bound to be like that, I suspect. A roadmap of how you got there with, you have to hope, a strong dose of yourself as well."

God walks through the room

Towards the end of our chat, I ask Smith if there's a sweet-spot between being readable and writable in terms of this kind of world-building - in terms of what you write down for people in terms of the way the society is structured, say, and what you leave blank for them to imagine. And how different is world-building in a novel compared to something like a movie or a game?

"I've always been a great believer in leaving space for God to walk through the room," Smith says. "In the sense of not crowding the reader's imagination, over-specifying, but letting them do some of the work. This isn't (purely) out of laziness. It's like that idea of uninflected images in film-making. Present one image, then another - let the viewer/reader fill in the gap. Doing so will make them part of the process, and let it feel far more personal and real to them.

"People tend to get obsessed with "rules" on the movie side. And in books to a degree, too. I tend to like to put down a few evocative things, and trust the reader to make their own reality out of it."

What I make of it is pretty simple. Books are weird. And maybe world-building is inherently weird too. There's a huge imaginative force in Only Forward - if I've been thinking about the neighbourhoods for the last twenty years, I'm pretty sure I'll be thinking of them for the next twenty - but the delivery of the book's ideas is so important too.

Chatting to Smith I've realised that the key to why its world-building is so singular and so refreshing is probably found in the reason the tone is so disarming. Smith had a plan, but he also allowed himself to surprise himself as he wrote. The fact that he would allow any idea that struck him to find its way into the city if he felt like it - some neighbourhoods are satire, some are references to his friends, some are just funny notions - allows the book to have this panoramic sense of potential, a sense that anything could happen within its pages.

At the same time, the fact that all these ideas that struck him came from his own head in the first places gives the thing a coherency and sense of identity and structure that ensures that the whole thing is in no danger of fragmenting into its various glittering pieces. If in doubt, only forward.

Next month we'll be visiting Ellen Raskin's Greenwich Village townhouse for an insight into what makes one of Manhattan's most storied addresses so special. And yes we're writing this here so that we actually have to do it now.

Thanks, as ever, to Paul Watson for the book photography.