Agatha Christie was a great games master

Spoilers.

This piece contains spoilers for The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

I read my first Agatha Christie book over the weekend - The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which I gather is actually a pretty stupid place to start as it's seen as being one of her best. Where to go from there? I wanted to read a bit of Christie in part because we'd just binged the cheerful pantomime of the Branagh films. Mostly, though, I think something had been put into my head when I read Stuart Turton's luminous mystery, The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, a few years back. Christie felt like a locked door, behind which a deeper understanding of what Turton was up to awaited. This is true, I think, but there's much more to it as well.

What surprised me the most - and I appreciate how stupid it sounds to be surprised by this - is how much of a game Roger Ackroyd is. It seems dumb to read a mystery novel and discover that there's something the reader can actually solve in there, but in my defence, the mystery novels I've read until now don't really bear that out. I don't read Chandler or Hammett or Mosley to solve the plots - I read it for everything else the plot allows for. With these writers, it feels like the plot exists to give the characters a reason to stay on the page being fascinating or illuminating the themes and preoccupations of the work. If all of Christie is like Roger Ackroyd, the reverse is true for her stuff. Everything in the book - characters, settings, tone of voice - is there to serve the plot itself. Roger Ackroyd is a book that exists purely to be solved.

A game! And with two billion books sold, this must make Agatha Christie one of the most successful game designers of all time. But why does her writing work so well as a game? If you're a fan of Christie, be aware that everything I'm about to say is pretty obvious. But if you've never read a Christie before, hopefully I can convince you to try one out.

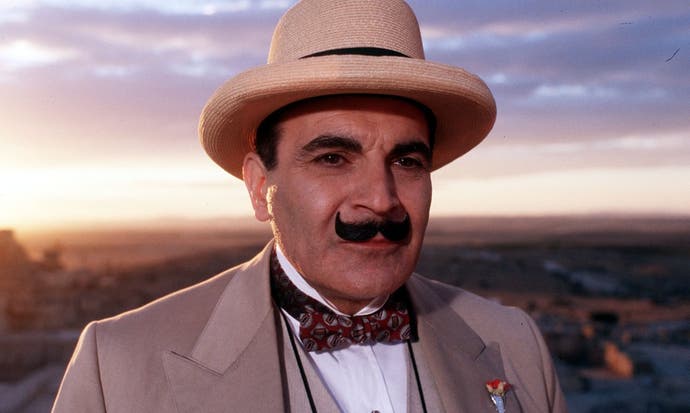

I'm going to spoil Roger Ackroyd in a bit, but for now all you need to know is that it's a fairly classic mystery set-up. A landed gentry type in a small community is bumped off in a mysterious way. Poirot is in the neighborhood where he's retired to grow marrows - this aspect may not be super classical I guess. And then over time everybody linked to the guy who was bumped off is revealed to have a more complex relationship than was initially apparent.

Let's get the obvious reason why this works as a game so well out of the way. Christie is surprisingly honest. She doesn't hide clues from the reader or bring them out - as far as I could tell - only at a late stage. All of the pieces needed to solve the mystery seem to me to be within the reader's grasp from a very early point.

On top of that she employs Poirot as a sort of games master. In Roger Ackroyd Poirot is only sort of the main character. Rather, the Watson-type, a local country doctor who narrates the book is probably the protagonist. Poirot is instead a sort of object of fascination a la Holmes - how does he work? What's he thinking? But he's also a classic GM: he talks to the narrator and, through doing so, he guides the reader's eye to certain aspects of the case and states and restates certain problems that must be solved. He keeps things going and gives readers and players certain puzzles to worry away at. Classic GM stuff.

But there's more, I think. And it's this extra coaxing to play the game that really marks Christie out as a master, I reckon.

Firstly, everyone in Roger Ackroyd is well aware of detective fiction as a genre and is versed in its mechanics. This doesn't mean it's a sort of 1920s Scream with self-reflexive jump scares and references out the wazoo. What it means is that everyone in the book is primed to see a murder as a puzzle to be solved - they're suspects, but they're also players.

And then the thing that really seals it for me: Poirot isn't just a detective. He's a famous detective. So the moment he turns up, everybody basically understands that they're in a work of detective fiction and they become even more open in their desire to get this thing solved, to obey the rules of the genre, and to play the game. Not for nothing, I reckon, that one of the book's best scenes takes place as suspects discuss clues while playing a few games of Mahjong. Games within games. Not bad!

I said I was going to spoil Roger Ayrkroyd, but I at least have a reason. If you don't want this book to be ruined, stop reading now.

As you probably don't need me to tell you, Roger Ackroyd is famous in mystery circles because it's the one where the narrator actually turns out to be the murderer. It's a sort of double challenge for Christie and the reader to pull off together. I knew this going in, and so the book had kind of a double appeal to me - or rather the whodunnit, which is always relatively compelling, became how-is-she-going-to-do-it, which I found irresistible. How is Christie going to conceal the fact that the person telling the story and framing events is also the person who the plot revolves around? And can she do this without cheating?

She did it without cheating, I reckon, although a closer reader than me might have spotted something I missed. (I assume I missed a lot.) And she did it so capably in part, I would argue, because as much as Christie is a novelist - the bestselling novelist in history - she's ultimately a game designer, and game designers have to work with these kinds of problems all the time.