AI-in-space caper Observation is about haunting yourself

Alexa-terrestrial.

Observation is trying to do something very complex, and if I feel, at times, like it's failing, I'm also not quite sure what "success", in this case, might look like. If I did, I suspect my ideas about existence in general would be rather different. The work of Glasgow-based Stories Untold developer No Code, the game casts you as an AI, SAM, aboard a damaged orbiting space station around seven years from now. In casting you as that AI, it also marks the point at which SAM ceases to be SAM and becomes something... else, a hybrid of human and machine traits, the player's curiosity and clumsiness mixed in with the AI's hitherto automated systems and procedures.

You struggle awake in darkness, starlight slashing remorselessly across a cabin hung with dust and components as the station spins in the aftermath of a mysterious collision. A woman is calling your name, her terrified face bleached by what you realise, with a start, is the light given off by displays and indicators that are, in some sense, "you". Announcing herself as Emma Fisher, she orders you to accept her voiceprint and give her access to the station's network, so she can work out what the hell has gone wrong. The trouble is, her voice doesn't match the print from your databanks. This creates the first of many introspective dilemmas, as you wrestle with the tension between what your mechanical faculties are telling you and the ideas and biases you bring with you, as the ghost forced into this machine.

"You can see that it looks like a glitch. An AI would reject it," observes No Code's co-founder and creative director John McKellan. "But a human would say, 'well, she sounds trustworthy, so I'll accept her'." The question of whether Emma is who she says she is, in other words, is also the question of who and what you are. "We wanted to create this sense of 'I'm meant to be in the walls' - I feel like I'm in the walls, like I'm the system, but the point is that right from the get-go, that's not your role," McKellan continues. "You're being asked to do that, but feeling like that's not your job anymore." Emma herself begins the game unconscious of your turmoil; as far as she's concerned, any delays or wayward actions on your part are errors brought on by the collision. This lumbers you with an unspoken second layer of objectives, on top of unravelling the enigma of your own being: either playing along with Emma, so that she doesn't begin to mistrust you and heaven forbid, try to deactivate you, or finding ways to communicate that you are not the mindless bundle of algorithms she takes you for.

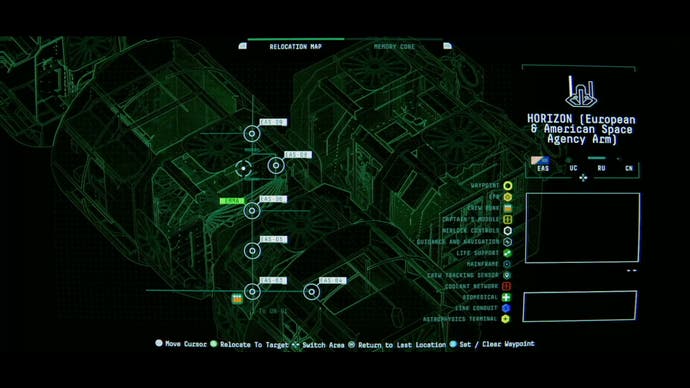

If all this is deeply thrilling, I'm not quite sure about No Code's reading of what a self-aware AI might make of itself - how it might visualise and operate its own senses and abilities. For all its vein of existential horror, and for all the gorgeousness of its visual design, Observation can feel rather workmanlike. It often plays like you are a nameless pen-pusher sitting at a bunch of monitors, hitting buttons, parsing feedback and triggering operations in the correct sequence. A rotating 3D wireframe hung with symbols gives you an overview of the station's modules. From there, you can switch to cameras within each module, panning the view to scan and interact with objects at Emma's instruction. Holding one button lets SAM say something about an object, such as a frozen door panel or a laptop containing a document you need to progress. The crackling, disorderly interfaces are a pleasure to dip into, readily recalling John McKellan's previous work on Alien: Isolation, but I often felt more like I was playing a more arcane hidden object game or dabbling with overwrought hacking puzzles in a Splinter Cell game, than engaging with the premise of a self-aware AI.

That said, the whole point of Observation, again, is that it's anybody's guess how such an entity might think, feel and behave. The game's interface and structure coalesce around a kind of eldritch blankness, the difficulty and perhaps, impossibility of expressing the transition from software to self-awareness. And if the game's visual design and puzzles occasionally feel like a pastiche of motifs and conundrums from less ambitious titles, it's also fond of throwing you off or hindering you, exacerbating the eeriness of its concept.

Naturally, the use of fixed camera perspectives sparks off memories of vintage survival horror games like Resident Evil. It means that both you and Emma - who you'll glimpse cruising through "your" innards in zero-G, which gave me a vague sense of revulsion - are at the mercy of line of sight. You're eventually given access to a floating spherical drone, which allows for full 3D traversal, but this is actually harder to work with than the stationary cameras. It's often difficult to grasp which way you're pointing, and the handling is purposefully woozy and erratic, suggesting an entity newly uncomfortable in its own skin. There are also bespoke interfacial puzzles that invite a bit of thought about you inability to read the code that comprises you, boiling it all back to an occult play of geometric symbols and audio patterns. One sees you dialling up and down the power of magnets in a newfangled generator, striving to bend a writhing knot of energies into a perfect circle.

There's also the sense of disconnection created by the architecture glimpsed through those fissuring camera feeds - it's as divided and incoherent as you are. As with Isolation's Sevastapol station, and as with the real-life International Space Station, Observation's setting is a rich cultural compound - the joint efforts of near-future European, American and Chinese space agencies, where the corporate chic of SpaceX rubs against the primary-colour nationalism of the 1960s Space Race, Apollo and Soyuz. This Frankenstein aesthetic extends to the interface, each screen the work of a different organisation - an intriguing rejection of the strongly unified, labour-erasing elegance that is today considered a hallmark of good game design. "One of the hardest challenges for me as a UI designer was to trying to make the UIs feel like they were built by different people," McKellan says. "It's not just one UI throughout the entire game. When you connect to the EFR, it looks and feels a bit different from other systems in the game."

Observation, then, is essentially a game about alienation, about finding your senses, functions and very physical structure placed at an unreadable remove or rather, rendered unreadable and alien by the very fact of consciousness itself, the inside-outside enterprise of self and other. You are not what you were, because there was no "you" to begin with. It's a beginning that sends questions spinning out in all directions, like debris from a disintegrating spaceship. Is it really helpful to think of the station as your body, when you are as lost inside it as the surviving crew? Then again, aren't we all somewhat lost in our own bodies, these strange, proximate things we think of both as ourselves and as extensions of ourselves, contraptions slaved to consciousness whose shadowy operations we take for granted till they run awry? During my 90 minutes with the game I sometimes felt dissatisfied with No Code's answers to these questions, but again, I'm as much in the dark about all this as SAM.