Alan Wake 2 review - incredible style, overbearing writing

Horror show.

I saw a stray tweet floating around last week - someone complaining that we've entered an era where most modern entertainment is now designed to be "smart" and "interesting" instead of "good." I wasn't sure what to make of this at first because personal taste is a wild and unpredictable creature that doesn't always obey logic. I also don't think "smart" and "interesting" and "good" are mutually exclusive concepts, or even especially helpful. It isn't possible to make a piece of art that withstands "the test of time" because it discounts the social and cultural context it was produced in - I am not going to run screaming out of a theatre because I think a real train is coming at me through the screen. But Alan Wake 2 is the perfect means to break down this smart and interesting vs. good sentiment, and in this way, it is perhaps the most important game of the year.

The latest Remedyverse adventure is an ouroboros of concepts born of the idea that complexity and complication yield the same result. If Alan Wake 2 was a painting, it would be Saturn Devouring His Son, except that Saturn and his offspring are both Sam Lake; it's a spectacle of postmodernism beaten into the ground by Alan Wake-shaped clubs, to show you it knows exactly what it's doing as both a piece of art and a commercial game and a story. It wants you very much to know that it is metatextual, that it understands the peculiarities and conventions and general disaster craft of writing. The first Alan Wake game, which I partly enjoyed but dropped off because it was a little too heavy-handed with its "my first book of metaphors" approach, already did this in 2010, and the obviousness of its writing is part of its whole concept. The Alan Wake of 2023, while still concerned with the same themes, is an entirely different creature.

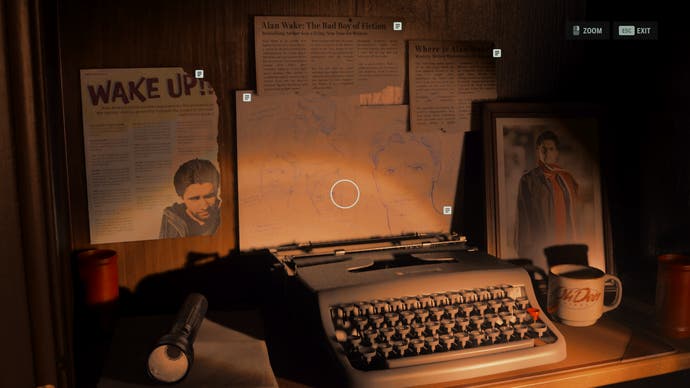

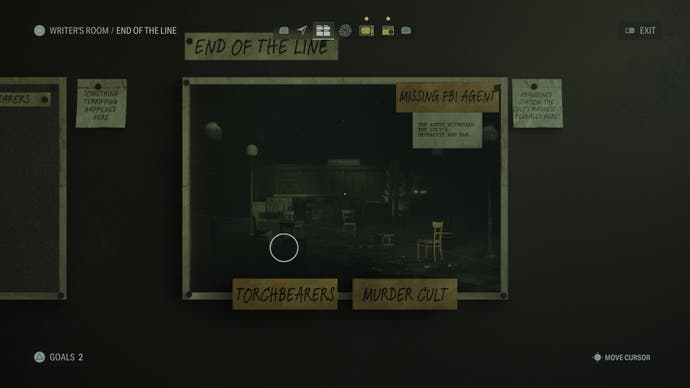

It's been thirteen years since best-selling author Alan got trapped in a creepy lake that isn't a lake. Arriving in Bright Falls are FBI agent Saga Anderson and her partner Alex Casey, who hates sharing a name with Alan's famous fictional detective. This is a role played by Remedy's creative director and game writer Sam Lake, a constant presence to underline the fact that autofiction is the backbone of the Alan Wake narrative. The feds are investigating a series of strange murders that seem to be related to the missing Alan, who ends up reaching out to Saga from his otherworldly jail. Gameplay switches between Alan and Saga as they explore Bright Falls and its surroundings as well as The Dark Place; Alan reworks story drafts in his Writing Room to reshape his prison, and the suspiciously intuitive Saga uses her "Mind Place" - her version of a mind palace - to organise her thoughts, analyse clues, and make deductions.

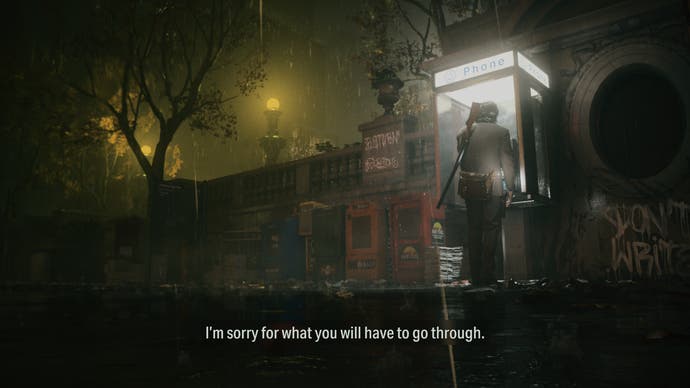

At its core, the Alan Wake 2 experience is like driving home in heavy rain as an adult and receiving calls from your mother every minute saying "be careful, the roads are wet!" while the car, the LED road warning signs, and your eyes all tell you the same thing. It is an exquisitely produced, gorgeously visualised, lovingly acted, remorseless onslaught of self-awareness and overt signposting to show the player exactly how stories are told, who tells them, and the limitations of genre; in horror, as Alan will remind you many, many, many times, there are only monsters and victims, and the ending must fit the genre. Nobody plays an Alan Wake game for nuance - laughing along with the tropes is part of the fun - but nobody wants to have someone whispering the whole movie into their ear at the cinema, even as a bit. "I can't believe I'm awake," Alan says in the final chapter without even needing to smile and wink at the camera. It's all an extension of the same themes as the first game - a pastiche of familiar devices, conventions, and self-aware metatextual references that shine a spotlight (pun intended) on the trials and tribulations of staying in control of your own narrative.

Where Alan Wake 2 is great is in its excellent synthesis of the original game concept with Control's incredible art direction and style; this sequel is undoubtedly a vast improvement. It's general knowledge that Alan Wake and Control share the same universe - they're bound together by a web of concepts and characters and objects that appear throughout all the games in various forms. There's a neat parallel between the importance of structure and cohesion in writing (Alan Wake), and the importance of organisation and taxonomy in a byzantine reality-defining institution (The Bureau's Oldest House). Both are concerned with moulding reality, whether that reality is fact or fiction, and when Alan Wake 2 leans into this overlap to examine fiction-making within the framework of Bureau research, it feels like we're going somewhere new and exciting.

Like the first game, it's Alan Wake 101 to understand that darkness is not your friend, but close-quarters combat against shades under these conditions can be frustrating. This new Alan Wake horrorshow takes full advantage of AAA's ongoing love affair with photorealism to maximise high-fidelity paranoia when navigating through shadows and dark spaces (and not just as a wink-wink double entendre as "shadow" is the Bureau's word for the Dark Presence).

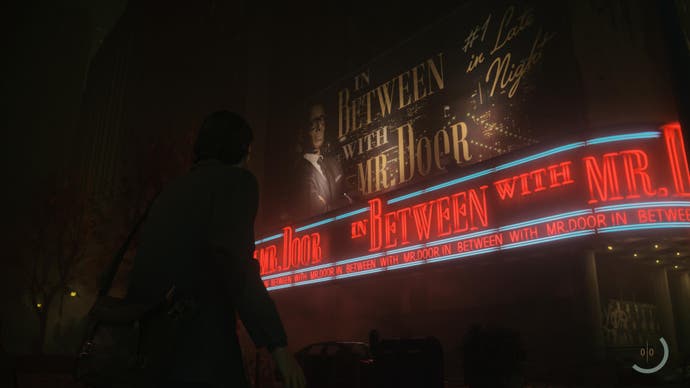

Saga follows a more or less straightforward detective trajectory - explore, examine, and retreat into the Mind Place to arrange her case board; she also collects oddly predictive manuscript pages and uses a Control-style weapons system that involves collecting said pages. Alan, while in the Dark Place, must out-write his nemesis by finding new scene inspirations in his environment - ideal settings like abandoned train stations and old-school cinemas that form the bread and butter of hardboiled detective fiction. His light mechanics, which help shift the reality around him and rewrite his own story, are some of the most satisfying portions of the game; the Writing Room is where he combines suitable scenes with different plot elements to push the story along. It quickly becomes clear that what Alan does affects Saga's world, and vice versa. Saga's journey, presented as the more materially "real" one, feels a lot meatier in combat; my go-to combo was the revolver and sawed-off shotgun, throwing in the odd crossbow shot when I unlocked the "magnetic pull" arrow upgrade.

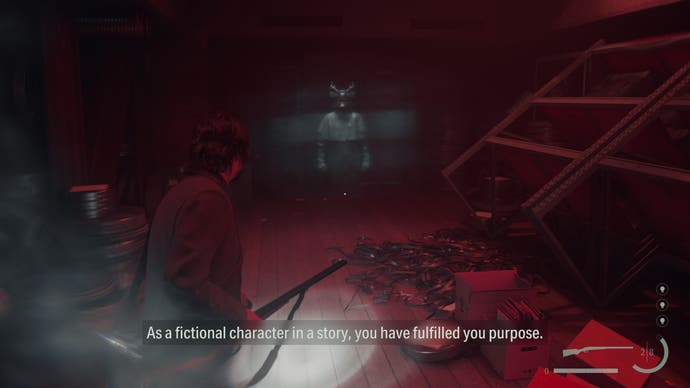

There are very few moments of reprieve from the constant metaleptic commentary, but the game and its increasingly superfluous exclamations ("The story is changing reality!" isn't shocking anymore after six hours) don't ever want you to forget you are playing fictional characters struggling to make sense of their own construction. Accordingly, there's a much greater sense of horror to this ordeal than the previous game - to understand yourself is an inherently horrifying experience. Alan's death screen, for instance, takes a delightfully grotesque page from old-fashioned slasher movies, and there's a conscious parallel between deconstruction and dismemberment as a means to enlightenment.

Unsurprisingly, Remedy's Control branding is everywhere - not just the obvious bits of geometry and lighting design - in the form of stylized projections and silhouettes and title cards and literal shifts in perspective. It's a logical adaptation of the moody X-Files vibe we got in Control to match AW2's pulpy detective settings, where Alan watches his most feted creation, Alex Casey, do his best Raymond Chandler. There are lavish setpieces and beautifully moody lighting and infinity mirrors/screens and ambitiously choreographed cutscenes; there are also collectable videos, which are some of the best parts of the game. If there's one thing we can all agree on, it's that Remedy knows style; Alan Wake 2 is, from a production viewpoint, a visual masterpiece, polished to a fine sheen by the unfailingly excellent Matthew Porretta and top-tier ensemble voice work. Every trope is beautifully executed - the gifted detective with a subpar home life, bumbling smalltown cops, cryptic backwoods folklore, the legend of a "cursed" piece of art, longtime partners comfortably moving in perfect sync, a payphone in a silent city that rings only for you.

But perhaps a game that repeatedly asks "where do stories come from?" is what we deserve in an age of unprecedented franchising and multiverse-mashing and revolving doors of reboots. When it comes to recycling without revelation, Alan Wake 2 has studied the blade. It wants you to know that it is aware of its own medium: that games are a unique hydra of technology, cinema, theatre, music, hypertext, architecture, and so on, and that Alan's magical metatextual adventure hinges on the player's participation as a reader but also a writer (the game will remind you, of course, that the writer is also the reader) working within a preset narrative. Alan Wake 2 is acutely aware of its lineage - it is a game that will launch a thousand lists about every piece of art and literature and film that came before it - and it'll surely dominate discussions about game narratives for the foreseeable near future. Most importantly, the player must understand that the story of Alan Wake 2 can only be told through the interactivity of games. But the metanarrative is only fascinating if you've never paid attention to these things before, which is hard because the game spells things out for you at every step of the way.

Alan's plot board and scene element mechanics is a meta-commentary on how everything is possible because nothing is original, and that you can't make something out of nothing. The game is consciously episodic in format, structured and styled like a streaming show to be consumed in designated portions. I cannot emphasise how much this matters when you're playing a game that reminds you of its own fictional conceit every few minutes, as if it's expecting you to have forgotten everything during a commercial break for tampons. Even when the Control-flavoured story portions hint at a new and genuinely interesting external point of interest, ultimately all roads must lead inward to Alan Wake, and by extension to Sam Lake, who very pointedly can't be untangled from his role and function as creator, character, and literary device. It's a bold move for a creator to plop themselves into the story as multiple characters wearing one face, but even bolder to assume people need their hands held to understand that masks and layers have been a foundational part of art since the beginning of time.

Is it unusually smart for a writer to demonstrate that they understand the influences and inspirations that have shaped their craft? Is it automatically interesting to have this self-awareness hammered home, even on purpose? Does it make it smarter or more compelling to amplify both of these concepts to the point of madness? Remedy fails to do anything groundbreaking with any of these things besides show and tell, but it does, for better or worse, make Alan Wake 2 the most extra game about writing ever made. If Sam Lake's intent was to make players as conscious as possible of the spiralling parallels between game narratives, the drive for self-improvement built into game systems, the exceptionalism that only one person can get the job done, and the writing process, he has done so ten times over with the finesse of an H-bomb with his face on it.

Alan Wake 2, at least for me, is ultimately a spectacle to be studied and dissected into bite-sized pieces about a very specific type of writing and writer; it's aimed sincerely and squarely at avid lovers of "I got that reference" bingo who don't need Alan Wake 2 to do anything besides be Twin Peaks The Return meets The Dark Half with all the worst impulses of David Foster Wallace and a protagonist very consciously styled like a mid-life crisis Donnie Darko.

The culmination of this approach is a game that feels designed to hit all the right cultural touchpoints without offering new insight or real bite of its own, besides "it knows what it is, with citations." And to its credit, Alan Wake 2 accomplishes its goals with verve and polish. But its narrative choices feel like a defence mechanism to validate its own derivativeness, even with the full knowledge that it has done all of this on purpose. It is not the first game to iterate meaningfully on the concept of loops, and it won't be the last, though it does marry its structure seamlessly with the writing process and the writer's ego, which will certainly feel monumentous for some. But action games are didactic by nature - we all must learn from tutorials and mistakes in order to win. The problem is winning in Alan Wake 2 feels like completing a beginner's course in media literacy - a beautifully presented one, but also one that doesn't reveal anything you couldn't figure out on your own.

A copy of Alan Wake 2 was provided for review by Epic Games.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)