Alien retrospective

In 8-bit, no-one can hear you scream.

There have been just four entries in the Alien franchise, not counting the incoherent fanwankery of Prometheus or the comic book nonsense of the Predator crossover movies. Of these, only one - James Cameron's excellent 1986 sequel Aliens - features an emphasis on gunplay and shooting.

Compare and contrast. There have been, by my reckoning and once again ignoring any Predator-related versus matches, around 18 games based on the Alien series. Of these, almost all feature lots of gunplay and shooting. Gearbox's Aliens: Colonial Marines at least has an excuse, based as it is on Cameron's allegorical war movie. Alien 3, a movie which rather pointedly featured no guns whatsoever, spawned an arcade game simply called Alien 3: The Gun. Such is the one-track mind of the games industry.

It wasn't always this way though. Way back in 1984, Ridley Scott's original movie got a remarkably faithful adaptation for various 8-bit home computers. Taut and tense, it's best described as a survival horror strategy game, where you guide the various crew members of the Nostromo around the confines of the ship, trying to evade the vicious xenomorph prowling the corridors and ducts.

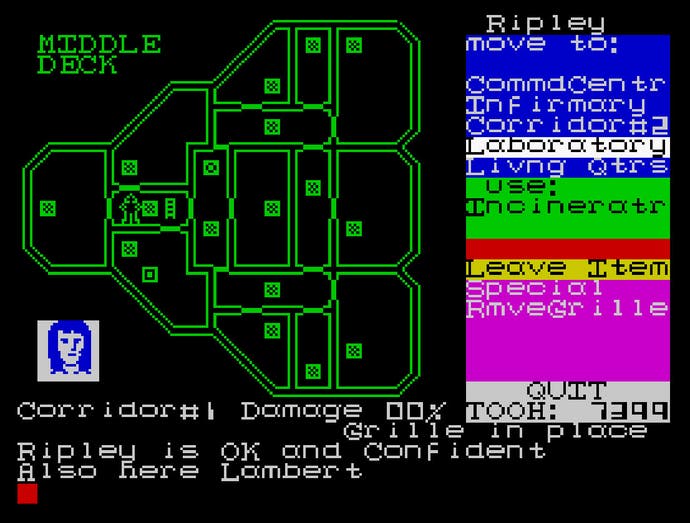

There's certainly not much to get excited about in the visual department. A stark top-down map of the Nostromo is your playfield, with basic stick figures representing the human occupants. A crudely formatted menu, with many of its options confusingly abbreviated to fit the available space, occupied the right hand side of the screen. From here, you could switch control to any of the surviving crew members and tell them what to do.

Your options were limited, but always logical. There were only a handful of usable items, but each was worth grabbing. A tracker pings out a warning if the alien is nearby. A couple of incinerators are your only defence against the creature - useful in an emergency but of limited use for a head-on assault. A fire extinguisher proved handy should the alien find its way into a vital system and start causing damage. There's even a catbox so you can catch Jones the cat, who pops up in random locations. It was a claustrophobic sandbox, where you could enact your own plan for survival.

Or at least you could try. Despite its threadbare appearance, Alien featured more than one innovative feature and one of these was something called Personality Control System. This meant that each crew member displayed basic emotions and personality traits, broadly in line with their character in the movie, and these would inform their response to your commands. For example, Lambert, played in the movie by Veronica Cartwright, is nervous and easily spooked. In the game, if things get too intense, she might refuse to move into the next room or enter a duct.

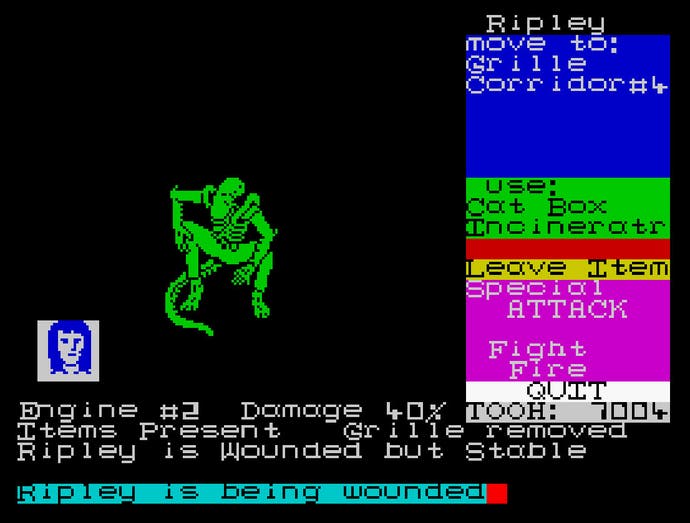

Make no mistake, this was - and still is - a creepy and scary game. The alien itself only appears as a looped animation, triggered whenever a crew member is in the same room as the beast, but its presence is felt throughout the game. With such basic visuals, the game instead turned to sound to crank up the tension. As you moved around, you would hear doors opening in other areas of the ship, or the sound of duct grilles being removed.

Played in isolation, these cheap 8-bit squawks and farts are meaningless, but in the context of the game it was a terrifying reminder that the alien is not only close by, but on the move. It's a simple trick, but a monstrously effective one, creating a mood of sustained panic and trepidation from the most rudimentary ingredients.

That, in itself, was pretty advanced stuff for 1984, but Alien had more tricks up its sleeve. This was a pioneering open-ended game, and one that wilfully deviated from the source material to keep you on your toes.

While most movie games stick slavishly to the script, Alien was a little engine of "what if?" fan fiction thanks to its random elements. The alien would hatch from a different crew member each time, and the identity of the treacherous company android would also shift from game to game. There were also multiple endings, with a variety of ways to defeat the alien and survive to enjoy the journey home. You could follow the script, set the Nostromo to self destruct and blast the alien out of the airlock before jumping in a shuttle. Or you could corner it and use your incinerators to kill it, at great risk to your crew.

The end of the game would offer a summary screen and a competence rating, judging your leadership skills and detailing the fate of each crew member, the Nostromo and the alien itself. It may be that dashing captain Dallas died immediately, host to the chestburster rather than hapless Kane. Ripley might fall to the slavering jaws of the alien, leaving Parker and Ash to team up against the monster. In the most unlikely - but tantalisingly possible - scenario, everybody would survive and the Nostromo would continue its voyage intact. All were possible, making it a game with near limitless replay appeal.

More than just an enjoyable trinket from a more innocent time, Alien remains a fantastic gameplay experience, the clunky graphics the only element that really betrays its age. Even played today, some thirty years on, Alien is still enormously impressive and it's little surprise that programmer John Heap would go on to explore the potential of flexible narratives and interchangeable casts even more ambitiously in the classic isometric adventure Where Time Stood Still.

What impresses most is that Alien managed to be so surprising, creative and effective even while being developed under the yoke of a major Hollywood license. A game-of-the-movie that manages to do justice to the spirit and tone of the source material while allowing players to completely rewrite the story on the fly? That's a remarkable achievement, regardless of the decade. If the imminent arrival of Colonial Marines has got you hungering for interactive xenomorph action, you really should fire up an emulator and give it a try.