Aliens versus Predator retrospective

Game, over.

"If it bleeds, we can kill it," mutters Arnie in the first Predator movie. Part of me wishes I could find a better line from the extensive canon of these sci-fi titans to bring you into this Aliens versus Predator retrospective. Something more intellectual, more profound. But to do so would be dishonest to the 12-year-old me who first played AVP in 1999. First and foremost and above all else, Aliens versus Predator is a game about blood.

Evidence for this is easily come by. There are four types of blood liberally spilled in Rebellion's 1999 offering of this most-rebooted of franchises. There's the acidic drippings of the Xenomorph, the fluorescent green life-fluid of the Predator, the strange white liquid that gives life to Weyland Yutani's synthetics, which I've always enjoyed pretending is milk. And of course, the familiar crimson that flows through our own veins and arteries.

Rebellion has always demonstrated a peculiar talent for portraying violence in an almost hypnotic fashion, more recently witnessed in its Sniper Elite games. But AVP's sanguinity has more about it than simple shock factor. It's also practical, systemic, symbolic. Kill a Xenomorph and it'll burst like a grenade, spraying deadly acid in all directions. It makes them a hazard to be avoided as well as a threat to be battled. Tag a Predator with a pulse rifle round and the bright green trail it trickles behind will lead you right to it, useful when fighting an enemy who is often invisible. Human blood, meanwhile, is little more than an aside, while flesh and bone serve as sustenance for the Xenomorph, or a prize for a Predator.

Point being, AVP is a cleverer game than it appears, and this extends beyond bodily fluids. Blood may be the subject, as 12-year-old me knew all too well, but it isn't what makes AVP interesting, as 26 year-old-me rediscovered just last weekend.

Story-wise AVP keeps it simple. As an alien you're tasked with defending the hive, and later infiltrating a shuttle bound for Earth. The Predator is searching for a fellow hunter being experimented on by Weyland Yutani. The Marine is simply trying to stay alive after becoming isolated from his squad at a research station on LV-426. It's a series of objectives loosely connecting the locations you visit. The only time another character speaks to you (or if you're the Predator/Alien, about you) is through one of the wall monitors scattered through the game, which transmit recordings of costumed Rebellion employees hamming it up in endearingly terrible fashion.

You soon find yourself clinging to these moments of poorly-acted human connection like a shipwrecked man to a piece of driftwood, because the rest of the time you're so desperately alone. Even playing as an insect made of knives or a weaponised Rastafarian, open conflict is best avoided. The Predator is clumsy and its weapons aren't designed for a stand-up firefight, while the Xenomorph needs to get in close to do any damage.

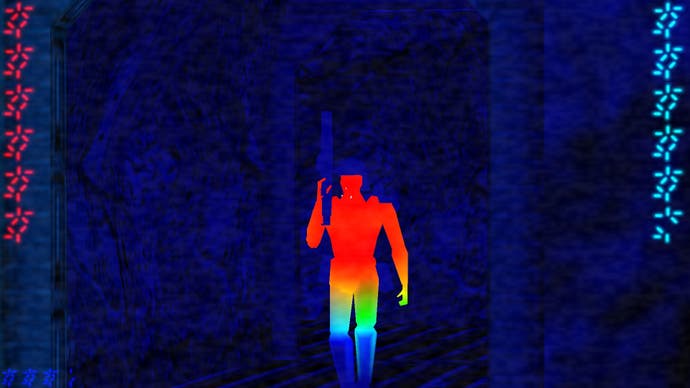

To gain the advantage, you need to use the majestically designed levels. The Predator's missions frequently offer high vantage points from which, using your various vision modes, you can watch terrified Marines hesitantly trying to seek you out. Meanwhile, the Xenomorph's ability to effortlessly scale walls and ceilings enables Rebellion to dispense with conventional level design logic and build pathways using all three dimensions.

These missions are a sequence of dizzying spatial puzzles constructed from looping ventilation systems, claustrophobic crawlspaces and honeycomb hives. They make you feel like such an intelligent little critter, encapsulating the films' portrayal of the Xenomorph as a beast that cannot be contained. They'll always find a way in. They really do come out of the walls. What's also interesting is how the level design changes to accommodate the enemy you're fighting. This is particularly the case with the Predator. Those high vantage points give way to long, straight corridors when the primary antagonist switches from Colonial Marine to Xenomorph outbreak.

As for the Marine, well, he's arguably the most interesting of all three. As a kid I always preferred playing the Xenomorph and Predator, because I was fairly timid and found the concept of inhabiting those creatures far more appealing than facing them down. This time around, I appreciated the thrill of the marine's vulnerability much more. Even the level design is against him, in stark contrast to the two extraterrestrial characters.

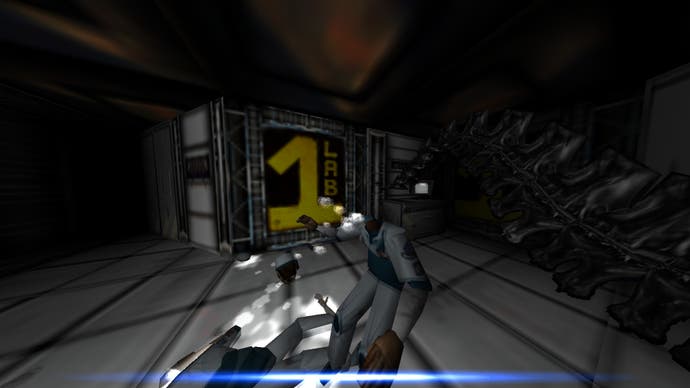

There's one mission in particular which highlights this, called Invasion. The player's goal is to navigate the atmosphere processing plant on LV-426, and turn five pressure valves located at different points in the facility, in order to overload the plant and thereby obliterate the Xenomorph infestation. The structure of Invasion is deliberately designed to disorient you, a twisting maze of corridors, elevators, staircases, gantries, pipelines, storage units and tunnels. Some areas of the facility only unlock after meeting certain criteria, while others are locked away as secrets that require shooting a specific light or perfectly timing a run to access. All the while you're constantly harassed by Xenomorphs, hissing, squealing, leaping at you from every possible angle. All of them potentially deadly should you let them into range.

It is by turns tense and intense, aided by the fact AVP plays so ridiculously fast. I actually found it off-putting at first, the way all three characters glide around the levels as though their feet are strapped to rocket-skates. I'm not alone - "Aliens versus Predator too fast" is apparently a regularly inputted Google search. But you get used to it, and then you realise how much the speed adds to the tension, knowing that if you aren't quick enough pointing your pulse rifle between yourself and a Xenomorph, you're facehugger-fodder.

Invasion marks the high point of the Marine's adventure, but the entire campaign is a fantastically frenetic and deeply atmospheric FPS. I recommend you switch off the somewhat obnoxious music, and leave yourself with the game's ambient sounds, punctuated by the tension-building bleeps of the motion tracker. In terms of audio-visual design, the game is still powerfully evocative despite its age. The lighting is employed with remarkable skill. Its hue, its positioning, its incorporation into play. You know when you enter a darkened building to turn the power on that, when the lights hum and flicker into life, they won't be the only thing energised by the pulling of that lever.

There's so much else I'd forgotten about in the years since I last played it, like how a Xenomorph will continue to come at you even when it's missing two limbs and a tail, while a severely wounded Predator will crouch down to initiate that devastating self-destruct sequence should you fail to finish the job. But it's a game that loves to surprise you. There was an instant toward the end of the Marine's final mission in which I was being chased toward a hangar bay by hordes of spitting-mad Xenomorphs. Backpedalling, pulse rifle rattling, I made it safely through the door with a sliver of health, and turned to see the ghostly silhouette of a Predator, the red light of its triangular laser-sight glowing in my direction. The creature held its fire just long enough for me to realise what had happened. 15 years on and the bastard game one-upped me!

As a series, critical favour has always resided with Monolith's sequel, probably because it is a more structured, more storied game. A perfectly valid viewpoint, but I prefer the immediacy of Rebellion's offering, the subtle design that supports the straightforward subject matter. It never needs to tell you what it's like to be a Xenomorph, a Predator, a Marine, how it feels to chase or be chased. Instead it demonstrates it to you through its manipulation of 3D space. It's a fitting coda to that pre-millennial style of FPS, short on narrative, big on display.

If you were disappointed by Gearbox's Colonial Marines, there's still hope - literally. The Classic 2000 version of AVP, available for just £3 on Steam, includes a Hadley's Hope multiplayer map which can be played solo or in cooperative multiplayer. See if you can survive longer than two minutes. Go on, I dare you.