Amarantus review - a superb visual novel that gives you revolutions within revolutions

Revolt text.

I seldom feel like completing a game's story twice, even when a single run only lasts 3-4 hours and I know I've left mountains of stones unturned, but Amarantus amply justifies starting afresh. It's not just that a second playthrough gives you the chance to know characters in different ways - seducing him rather than her, or perhaps both at once; alienating an old friend while forming an unnervingly close bond with somebody who, last time round, threatened to kill you if you let your ideals get the better of your empathy. Nor is starting again just about uncovering what's really going on with the wider plot, with multiple playthroughs introducing people and backstories that exist initially as shadows, dancing between the lines of the prose and in the delicacies of character performances.

Amarantus is a tale of political revolution, but revolution can also mean repetition, and repetition is crucial here, not just in terms of learning and "mastering" this glorious visual novel's small, rewarding assortment of choices so as to reach the Best Ending, but also in the growing resonance of recurring scenes that explore "recurrence" as a theme. Starting again isn't simply about learning what you missed, and making less-terrible decisions. It's about learning what it means to start again, though it's hard to say more without spoiling things.

That's my grandiose armchair-Walter Benjamin reading of Amarantus, anyway. You can also play it purely for the joy of hanging around some brilliant, damaged-but-not-broken people, having ill-advised sex, getting into ill-advised fights, and doing various other silly things that always make for a gripping adventure. There's every kind of emotion at work in this game: desire, joy and bitterness, explosive anger or sadness and scenes of throwaway kindness or sparkling wit or believable mundanity.

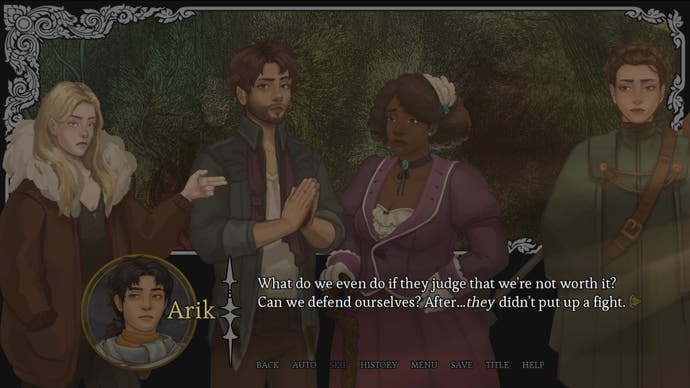

The game follows a small band of unusual suspects who are trying to overthrow a tyrant, Lord Caudat, against the backdrop of a forever war with a country overseas. You play Arik Tereison, whose dissident parents are arrested by Caudat's goons during the prologue, and who promptly sets off to the capital city for retribution. Much of the story is about deciding what kind of revolutionary you want Arik to be - a public usurper, a voice of reason striving for a bloodless transfer of power, a knife in the shadows - while reckoning with the reality that he is no kind of revolutionary at all. He's a brash 20-something with no plan beyond getting some payback, and minimal experience of political organising, let alone things like sword-fighting or palace infiltration. His role is less to become the hero of the resistance, though that's an option if you make certain decisions, than to serve as a source of narrative momentum.

It's just as well, then, that he has some really supportive and forgiving friends - or at least, driven and tenacious allies - who hail from all levels of the game's understated fantasy society, and who bring their own moral codes, experiences and communication styles together with heaps of baggage and yearnings you can satisfy or frustrate or talk your way around - achieving a different, but complementary understanding of that person every time. These characters are smartly distinguished both in terms of the writing, which strikes a balance between modern English dialects and arcane flourishes (there's a pronunciation glossary that actually has a bearing on the plot, rather than being a cute appendix), and the game's lush collection of 2D character postures and expressions.

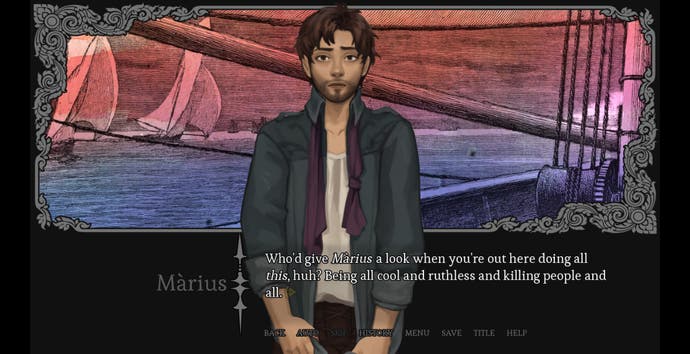

Arik's closest friend is Mireille: conciliatory, responsible, extremely rich. She has a way of pushing her hand forward at waist level that can express both sisterly concern and passive aggression. There's also her tearaway brother Màrius, who is puppyish, slender and self-deprecating, with surprising reserves. Where Mireille always appears grounded, resting on her cane, Màrius can't seem to work out what to do with his arms during chit-chats. He tangles them round his head, wrings his shirt tails or presses his palms together like an eager pastor - a gesture that gives the game some of its funniest moments.

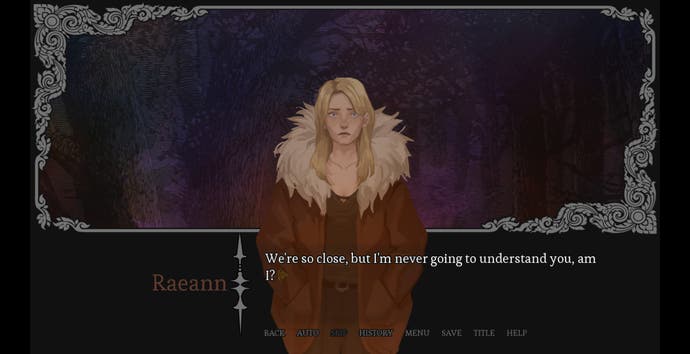

Màrius has a thing for Raeann, a flinty and sarcastic street urchin whose capacity for side-eyeing the player is exceeded only by her capacity for spontaneous violence. She's the character I worried about most, during my first run, but in certain ways, she's even more vulnerable than Màrius. The guardian of the group is the towering Major, an older, wintry mercenary whose hands are mostly visible when she's saluting or hefting a rifle, and whose soft gaze is awash with memories of war and tragedy. There are other characters as significant as these - including one whose, shall we say, unique degree of intuition turns the group dynamic upside-down - but I won't spoil their introduction.

Play consists of conversations with some or all of these characters, set against superbly sketched and embroidered backdrops that, together with a magical guitar soundtrack and some lovely ambient audio, immerse you in forbidden woodlands, echoing stone halls and the creaking chambers of a ship. Within these florid, breathing spaces, the cast move and act with an expressivity you rarely see in photorealistic blockbuster games.

Amarantus does quietly amazing things by way of deceptively simple questions of tempo and framing and narrative context. Characters move across the screen, look outward at you or each other, step into the foreground or hang back in the corners, speak with different cadences, and talk over each other believably (there's no voice-acting, but I don't think the game needs it). Far from feeling like evidence of limited development resources, the repeated poses and gestures become mannerisms that read differently depending on the situation. A simple source of intrigue is that you'll typically talk to several people at once, and it's always worth halting to trace each person's reactions - the Major closing her eyes wearily while Raeann jabs a finger at Màrius and Mirielle glances at you for direction.

You never have much say over the nitty-gritty of these scenes, and Amarantus is better for it. Only at sparing intervals does the game offer you a choice, and all the choices are Big Choices, including the ones that seem perfunctory. Who should you ask to train with whom? Who do you send to a nearby town? What exactly do you plan to do with Caudat, when you encounter him? Which budding romantic relationships do you encourage, and whose trust do you betray? The thrust of the plot remains the same, regardless of your decisions - you'll head to the same places in the same order, and as far as I can tell, there are no premature Game-Overs. But the decisions you make greatly affect how characters respond in subsequent scenes, which in turn shapes Arik's own trajectory as a would-be Che Guevara.

The small number of decisions available to you also allows Amarantus to exist easily, comfortably in your head as a piece of stage machinery. I can remember every step I took along the way in each playthrough, pretty much, and make immediate connections between choices and outcomes, even when they're squirrelled away in the detail of conversations.

As such, the game also gives you a ready grasp of the knottier philosophical questions that inform, and are informed by your relationships with individual characters, as you go about hunting down Caudat. Replaying the tale feels like reassembling a broken watch, to me: I know where the critical workings are, and the more I put them together, the better I understand what they're for. It feels like a well-defined structure I can participate in, for all my lack of control over the minutiae, where many genre fantasies often drag on forever and lose you in the weeds.

Starting over inevitably means you'll have to re-read a lot of the prose, of course, though Amarantus has a history function that lets you warp around the timeline. Repetition also exposes the game's slight overreliance on concluding exposition: a lot of hints and speculations come to a boil in the closing moments, and while the story is sort of about developing a portrait of your adversary even as you forge Arik into a potential usurper, much of Lord Caudat's characterisation happens rather late in the tale.

But the knowledge you obtain from completing the story once, together with those new people and elements during repeat playthroughs, also brings fresh import and texture to the script. Random thoughts, slight changes of expression and even silences or the pacing of the dialogue text, gradually reveal their relevance from run to run, as though you'd found the hidden catch in a puzzlebox that causes it to open magically in your hands.

And then there's that theme of recurrence. There are spaces and moments in the game, viewed initially with simple curiosity, that develop haunting implications during your second visit. They don't merely add to the story, but encourage you to step away and view this revolutionary fable as part of a tradition of narratives about power and its overthrow. I've referred to Amarantus as a watch and a puzzlebox, but in this sense, it's more of a cage: an elaborate, revolutionary but also reactionary framework, within which you and your long-suffering friends must carefully position yourselves, lest it make your choices for you.