How a young Iraqi programmer tried to adapt Gilgamesh, the oldest surviving hero story

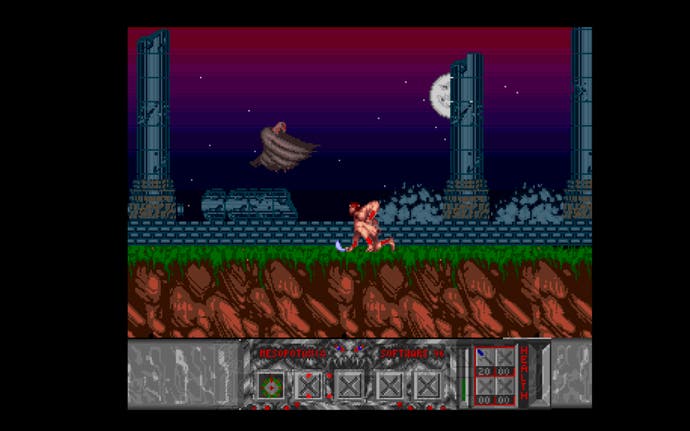

Amiga classic.

The world's oldest surviving work of literature begins and ends with a wall: the rampart of Uruk-the-Sheepfold, great city of ancient Mesopotamia. "View its parapet that none could copy!" reads Andrew George's English translation. "Take the stairway of a bygone era". Uruk's wall is the crowning achievement of Gilgamesh, warrior-king, wanderer and cosmic nuisance. When we meet him in the poem he is terrorising his own subjects, brawling and womanising like only a 17-foot-tall demigod can. So the gods make Gilgamesh a rival to keep him busy: Enkidu, "offspring of silence", a beastman moulded from clay. Having fought each other to a standstill, the pair become friends and go on bloody masculine adventures, ransacking a holy cedar forest and slaughtering the Bull of Heaven, a creature whose very breathing causes earthquakes.

Then, tragedy strikes. Outraged by these antics, the gods decree that Enkidu must perish of sickness. Gilgamesh is distraught at the loss and the accompanying revelation of his own mortality. Forsaking his throne, he embarks on an arduous search for Úta-napíshti, undying survivor of an apocalyptic flood, to learn the secrets of eternal life. He races the Sun itself through the netherworld, and crosses the Waters of Death to Úta-napíshti's home. But the immortal man cannot help him. "You fill your sinews with sorrow," he warns. "Bringing forward the end of your days." He offers Gilgamesh a plant that can restore youth, if not avert death, but the plant is stolen by a snake - the origin of the snake's ability to shed its skin. The king returns to his kingdom in despair. But in the final lines of the "standard" edition, he takes consolation in the spectacle of Uruk's inimitable wall, enclosing the text as it does the city, symbol and guarantor of his everlasting fame.

The epic of Gilgamesh is the blueprint for generations of heroic narratives: as macho and gruesome as Homer's Iliad, as intrepid and mournful as the Odyssey. Its subject matter is varied and vivid: prostitution, dream rites, dismemberment, the baking of bread. But above all, it is about fear of death. "It's something I think should be studied in all elementary schools around the world, as one of the first pieces of literature where human beings start thinking about these questions," says Auday Hussein, founder of R&D and consulting company Mesopotamia Software, who is completing a PhD in archaeology at the University of Heidelberg. "Who am I? Why am I here? What is in my power? Where is my limit?" The character of Gilgamesh - likely a real king, probably not 17 feet tall - has been copiously adapted and reinvented since European archaeologists began translating the epic in the 19th century. But the epic itself is relatively unknown outside the realm of academia, overshadowed by the hero fables of younger civilisations. "It's deep philosophy that we had 5000 years ago," Hussein goes on. "And nobody wants to talk about it - it's scraped under the carpet."

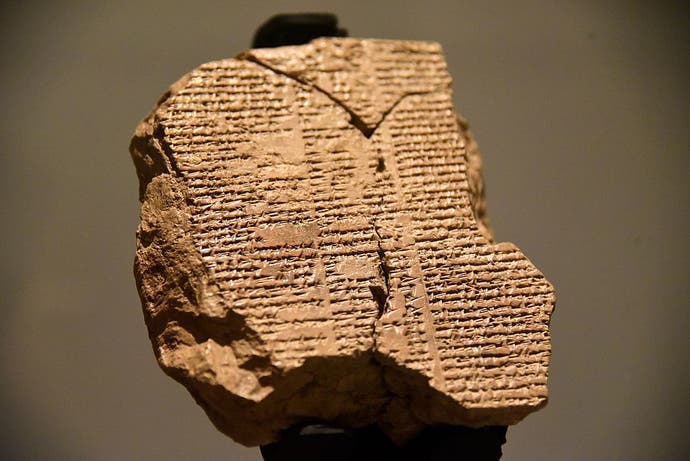

Part of the reason for that may be the text's incompleteness. It consists today of dozens of fragmentary clay tablets of cuneiform writing, mostly Sumerian and Akkadian - a collection of episodes and perspectives from many authors, written and rewritten over thousands of years. The recovery of those tablets has been complicated by more recent acts of bloodshed and conquest. What was once Mesopotamia has become the territory of Iraq, together with parts of Iran, Turkey, Syria and Kuwait. The first Gilgamesh tablets to be translated were among thousands of artefacts taken from the region in the day of the British Empire. Subsequent US-led invasions have at once damaged historical sites and precipitated a bustling illegal trade in archaeological finds: the latest Gilgamesh tablet to be translated was purchased from smugglers in 2011.

Auday Hussein cut his teeth as a programmer and designer in this later, troubled period. He grew up in Baghdad, a few hours drive north of the site of Uruk, during the reign of the tyrannical Ba'ath Party. Armed with a passion for both Mesopotamia and programming, Hussein once sought to develop an Amiga adaptation of Gilgamesh's legend. It's tempting to characterise this project - itself a fragment consisting today of one playable region - as an assertion of his cultural identity in the face of foreign incursions and plundering. But that's not how Hussein sees it. "I think, in today's world, the word 'identity' is an archaic one. I might have more in common with someone in Japan, Nigeria, France, Honduras, etcetera, than I might have with my neighbour next door." For Hussein, Gilgamesh transcends individual cultures; he is everybody's forebear, driven by the most fundamental of anxieties. "I want to share this with others, just like I want to share other things like the Iliad or Greek philosophy - all these things that I'm proud of as a human being."

Hussein took his first steps into programming at the tender age of 12, when Iraq's home computing market was in its infancy. His first computer was Microsoft and ASCII Corporation's MSX - the birthplace of Metal Gear, localised for Arabic markets by Kuwaiti company Sakhr Software. "The Iraqi government at the time had some kind of contract to import a massive number of these machines to Iraq," he recalls. "And I was one of the luckiest people there [because] my dad bought me one of these things. The first time I saw it, I couldn't believe it. Because my mom is a programmer, she worked with the Fortran language, and when I went with her to work, the computers were like big fridges with punch cards and tapes. So when I got this little keyboard that's called a computer, I thought: that's the computer? It should be a room!"

Hussein experimented with coding his own games in BASIC - he has a lifelong love of racing simulations, albeit qualified in later years by awareness of the environmental impact of car travel. But he soon found that his ambitions exceeded the language's capabilities. "It's very slow, it doesn't have access to the graphics and all these things." He gravitated to assembly and machine code after discovering the MSX Zen programme, often relying on reverse engineering to make progress in the absence of proper guidance. "I had to do some tricks using the instruction book from BASIC to force the system to show all the different instructions. And from there I learned how to use it by trial and error, because there was no access to these materials in Iraq, and nobody there knew at the time what machine language was - it wasn't important for people to go to that deep level of closer-to-the-metal programming."

Then came the Commodore Amiga, which began to appear in Iraq in the late 1980s. "I had a relative in the UK who sent me one. And with the Amiga, things started to change [for me]. It's a perfect machine." Unlike with the MSX, Hussein was able to get hold of books about coding for Amiga, and magazines such as Amiga Format - often bought by individual programmers during trips overseas and passed around as photocopies. "We got to the chipset level, we knew every single wire coming from this chip to that chip, and how you can control the hardware completely."

At this stage, Iraq had also developed "a big community of programmers and hackers" bolstered by state-supported youth clubs, which offered programming courses, lectures and competitions. "That was one of the few successful things that the old regime in Iraq [did], which as you probably know was not the best regime to be under - it was a dictatorship, really harsh and cruel. But it did a couple of things here and there that were good and successful, including importing computers and [establishing] these youth centres. Of course, after a while they become too political and everybody had to leave who was actually curious about programming."

His enthusiasm for racing aside, Hussein had long wanted to make a game about ancient times. While learning English as a schoolboy, he had pored over UK-published Ladybird books with their luxuriant depictions of Roman, Greek and Islamic history. "When I got into programming, the first thing I thought about aside from racing was how to bring that passion for history into games - how can you recreate these worlds?"

As a young student, Hussein collaborated with a friend, Rabah Shihab, on the Amiga game Babylonian Twins, a joyful platformer set in Babylon in 576 BC. Remade and released for iPhone in 2009, the game includes gorgeous portrayals of old Babylonian landmarks such as the blue-tiled Ishtar gate. But Hussein wanted to go even farther back, to where Mesopotamian literature began. "I'm a big fan of the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer - they are fantastic, I've read them in so many versions and I know all the characters in every scene. I'm going to tell you here, Gilgamesh is deeper - it's not as exciting, it's not as Hollywood-ish, let's say, it doesn't have as much action, but it has philosophy and it's deeper. It's like, the man who thought he was the master of everything."

His plan at first was to recreate the entire story of the standard Gilgamesh epic, all the way from the warrior-king's salad days to the grief and hardship of old age. Working as designer, programmer and art director, he enlisted a university friend, Ali Aboud Al-Gaffari, as artist, and a high school friend, Mahir Hisham Al-Salman, to create the music. Shihab lent a hand by sharing tools he had written for Babylonian Twins. "Like the editor, for example, it's a tool he used to design the whole background. That took lots of work, and he did the whole thing - I just took it from him to make my game."

The trio worked around the clock to fit the project in alongside their studies. "We had two Amigas between the three of us, no hard drive, we had to swap discs," Hussein says. "I programmed at night and the artist worked through the day. He didn't have an Amiga so he came to my home and worked on my computer while I was doing other things, planning and stuff. And at night when he left I took all his art and tried to program it into the game, till the morning. It was that circle."

Al-Salman had access to his own Amiga, but perfecting the game's sound effects was still one of the project's biggest hurdles. "Nobody knew at the time how to make actual proper sound effects. So we had to improvise. For example, the sound of a waterfall - we turned the faucet and put something over it to spray the water out and make it a bit noisier. For the sound of fire we just put some oil in a pan and started overheating it, almost causing it to smoke. And then with sampling we managed to get some nice lava and volcano effects."

Developing a game in the aftermath of the Persian Gulf War was no mean feat, as Rabah Shihab's interviews about the creation of Babylonian Twins attest. Iraq's infrastructure, once an object of envy across the Middle East, had been devastated by coalition bombing. The economy was in shambles and electricity supplies were precarious. But in the end, the greatest challenge Hussein faced when adapting the epic of Gilgamesh was doing justice to the intricacies of an incomplete and enigmatic text.

In the first part of the "standard" edition of Gilgamesh, the king and Enkidu set out to pillage the gods' own cedar forest on Mount Lebanon and slay Humbaba, a monstrous guardian set there by the god Enlil. Even taking into account the decayed state of the tablets, Humbaba's form is eerily undefined. He is "a man who must not be looked on", says Enkidu, whose "voice is the Deluge". His body is cloaked by seven "auras" or "terrors": in the 2011 tablet recovered by the Sulaymaniyah Museum and translated by Professor Farouk Al-Rawi, these are described as Humbaba's "sons", with names like "Typhoon" and "Screamer".

"How do you depict that?" says Hussein. "How do you get the shape of Humbaba? We tried to work on that first. And everything that we came up with, or the artist came up with - I don't know, it just felt very simple, very one-dimensional." The developers also struggled to picture the mighty Bull of Heaven. "Is it a winged bull? Some people depict it as a winged bull, but it's not. Is it a bull with a human head? We don't know. Is it just a gigantic, angry bull? How big is it? So we tried also with that, and I wasn't satisfied, to be honest."

For Hussein, faithfulness to the subject matter was paramount. "I didn't want to take too many liberties, right? I value the work I'm making a game about more than my game." He confesses to worrying a little about the more cartoonish aesthetic of Babylonian Twins. "It took the Mesopotamian archaeology and style in a very comic direction. At that time I was not very happy with it. Now I look at it and I understand it, I think it's fantastic because that's what we need to do - we needed to simplify things for the audience in a creative way, not in a cheesy way."

More significantly, he came to feel that to visualise the epic was to travesty it. While the text includes some wonderful descriptive passages - the 2011 tablet offers a luminous account of Humbaba's cedar forest and its raucous birdlife - it leaves much to the imagination. "Once you try to put it into some kind of drawing, I think it loses a lot," Hussein argues. "So I was discouraged by everything we tried to make." (It should be noted, of course, that translating the text into English entails plenty of compromises. "Akkadian is a complex language that has its own features," Hussein points out. "Also, Babylonian poetry has its own style and structure. The modern English translations try to write the sentences in proper English style, and I think much of the original poetry is lost with that. I would rather focus on keeping the essence of the original poetry, even if the English is broken.")

With these considerations in mind, Hussein eventually decided to depart from the source material and create an original game, albeit one heavily influenced by Mesopotamian art. "I didn't want to give myself too much liberty, I was very worried about doing things like that. So very quickly I decided, you know what, I'll give myself the freedom of making a game without having to worry about being dishonest to the story." The shift of direction proved invigorating for Hussein's small team. "We said, you know what, let's just forget about this story. Let's just do whatever monsters we want. And then once I said that, I just got the most beautiful art I can think of from that artist - the creativity, the animation, it's fantastic."

The game as it exists on Hussein's hard drive today has the working title "Kingdom of Death". It's a 2D platform adventure with a musclebound, sword-wielding hero and a vast menagerie of monsters spread throughout intricate, cavernous environments. It takes inspiration from a multitude of non-Mesopotamian sources, including Shadow of the Beast, Zelda and David Joiner's 1987 RPG Fairy Tale Adventure, and is "more free, more open" than the Gilgamesh narrative, with puzzles that pull you deeper into the setting.

The puzzles are linked to cuneiform inscriptions on background surfaces (fortunately for the non-Assyriologists among us, the game provides English subtitles). "In one place, it tells you even the darkest places could give you a hint about something. What does that mean? Okay, so I need probably to go to some dark place and light it up. Where do I get the light? You have to think about it. it's an adventure game - when I grew up, I used to play games like that all the time." Hussein's account of the game's introductory section puts me a little in mind of the open-ended boss structure of the Dark Souls games. "There's five big bosses in this level you have to fight who hold the entrance to the Kingdom of Death, or something like that, " he says. "We didn't put it directly in words, but the theme is that you are in the underworld and trying to get out. We tried to make it a bit more abstract. It's up to you to imagine what's going on."

If Kingdom of Death is a more "generic" game, in Hussein's words, it still channels something of the Gilgamesh epic's atmosphere of horror and desperation. One of the Kingdom of Death's guardians, a dragon, is defended by his own offspring. "You'll fight the sons and they'll both get killed. And then the boss comes in. And although he's supposed to be your enemy, he's still a creature and he still has emotions. He's terrified by the death of his sons. He gets really angry and sad at the same time."

Beyond the underworld's threshold, there were plans for a magnificent temple environment, decorated with enthroned statues and carved lion's heads exuding rivers of gold. But this, alas, was not to be. "The project took much longer than I wanted it to take and by the time there was a fully playable level, the Amiga platform was dead and the prospect of publishing the game was fading out," Hussein says. "At the time PS1 was just out and seeing the 3D graphics of Tekken made it clear that while I've been stuck in my cave making this game, the world [has] moved on and the Amiga is no more."

Hussein left Iraq after graduating university, teaming up with his old friend Rabah Shihab to found the award-winning Dubai-based multimedia consultancy Cosmos Software in 1997. In the decades since he has racked up credits at game developers across the globe, including EA, Relic Entertainment and Slant Six, and is currently working with Klei Entertainment in Vancouver on a port of Don't Starve.

He still entertains hopes of completing the Kingdom of Death project, though he cautions that it would need to be reworked to suit prevailing standards of difficulty and accessibility. "I just fired the game up on an Amiga emulator on my Mac, and played in God mode, and it still took me about two hours to finish. It was freaking hard!" But in general, Hussein feels that his days as a designer - and a player - are behind him. "I was a gamer on Amiga and MSX, and once Amiga was gone I never played games at all. Although I've been working in the games industry for 35 years or so right now, my work was always very technical, very close to the metal. I've been a consultant since 2008, working freelance contracts, I've never worked full-time for any company since then. And I when I take a contract, the first thing I do is tell them I don't want to be involved in gameplay. Tell me what the game's about, show me the the technology. I'll understand."

The exception is Hussein's part-time passion project Impulse GP, a WipEout-esque hoverbike racer with ecological themes, which released on iPhone 5 in 2015 to much acclaim. Created over four years, the game is a technological masterpiece, made from scratch with no third party components and running at 60 frames a second. It certainly reflects the ingenuity and dedication Hussein displayed as a rookie programmer in Baghdad, with a custom-made “Trackmaster” course editor that allows for speedy design and testing. "I had designers and artists just bringing their art from Maya or any other application that makes 3D objects and importing them into this tool, and then start just paving their track along the line - they just draw the line and the track goes on, they can twist it and do everything in a very easy way. You can basically design a whole track within a couple hours, with all the environment around it and everything, and you can actually play the game in Trackmaster while you design it."

Hussein's love of Mesopotamia, meanwhile, has found an outlet beyond games: he completed an MPhil in Assyriology and Archaeology at Cambridge University in 2019. His PhD focusses on the palace of King Sennacherib in the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh. "Part of it was destroyed by ISIS, and I'm trying to document the history of that palace," he explains. "To connect the archaeological evidence that we have from the last 200 years of excavation, with the description that the king himself wrote from Mesopotamia 2700 years ago."

Which brings us back to Gilgamesh's account of Uruk-the-Sheepfold, the triumphal work of architecture that will carry his legend into eternity. The obvious irony of his declaration that Uruk's great wall is beyond imitation is that we only know about it thanks to copying, recreating and rewriting. The Gilgamesh epic is no single, self-sealed artefact but a work-in-progress aggregate of texts in different languages, painstakingly transcribed and iterated upon from century to century. Following his rediscovery in the 19th century, the king has outgrown both Uruk and Mesopotamia: he lives on in operas and Japanese visual novels, in ferocious arguments over the influence of Úta-napíshti on the Bible's Great Flood story, in North American environmentalist fiction, thrash metal music and superhero comic books. While it is no longer a retelling of Gilgamesh's adventures, I think of Hussein's project as part of this lineage of adaptations - all pursuing the same, abiding questions and desires in very different times and places.

It's important to give these variations a source, however, and to understand how they reflect a hierarchy of cultures shaped by geopolitical power. While he feels that Gilgamesh's story is larger than any one society or identity, Hussein would like Mesopotamian art and literature to receive its due alongside the more celebrated and disseminated works of civilisations such as Ancient Greece. "Some of them get the first page, the cover page all the time," he says. "Like Egypt, Rome, Greece - in all periods, it's those three civilizations. Everything else gets pushed into the background. And sometimes justifiably! It's not that Mesopotamian civilization is better or worse - once you try to put it in these terms, you just lose any credibility, because there's no better or worse. The world is a continuous series of developments in different places, and things pop up here and there. There are always people in different parts of the world developing something, and being creative."