Anodyne 2: Return to Dust review - Zelda and Psychonauts combine in a bewitching formal experiment

Inside out.

I haven't seen sunsets like this since, oh, 1996. Explicitly modelled on the look and feel of 3D PS1 and N64 games, the island setting of Anodyne 2 is like a version of Hyrule Field engulfed by the coral reefs of Square Enix's Chrono Cross. It's an exquisite recreation of a lost period in videogame landscaping, from the aliasing on the waterfalls to the smudgy paintings of distant environments that serve as portals to other areas. For all its pristine historical specificity, however, this realm is host to a creeping decay - the Nano Dust, an enigmatic force that infests the minds and bodies of New Theland's residents, giving rise to (or at least, revealing) strange anxieties and desires.

Which is where you come in. You play Nova, a silver-clad, spiky-limbed agent of recovery hatched from an egg by the Center, the island's unseen creator and overseer. Using your ability to shrink to microscopic size (which involves a faintly mystifying, but pleasing, rhythm-matching minigame), you must teleport into each New Thelander's soul and clear the blight from their inner workings with your vacuum gun, vanquishing odd fancies let loose by accumulated Dust. You'll then offload this Dust at a containment facility in the game's one city, Cenote, where it can be used as energy to push back the island's Dust Storms and expose new areas. It's in the act of shrinking that Anodyne 2 plays its ace: curled up inside each character's psyche is another, older kind of game, a beautifully wrought 2D mosaic dungeon in the spirit of Link to the Past.

This is industry history defined not as the heedless march of technological progress, but as the rings of a tree - hardware constraints, design conventions and aesthetics traditions wrapped around one another. Except that's far too static a metaphor: Anodyne 2's achievement lies with how it goes beyond even the brilliance of its generation-switching conceit to embrace a universe of shortform experiments. In the process, it also creates scepticism for the ethic of symmetry and authorial control represented by the Center, as Nova learns to perceive the Dust in a less fearful light. The game's overarching fable is quite straightforward, for all the mildly terrifying theoretical flair and self-reflexivity of its writing. It is a coming-of-age tale, about learning to live with life's ugliness and uncertainty for the sake of life's beauty and surprise.

As in the old Zelda dungeons, each inner world is its own little bespoke, Polly Pocket confection of props and stories, resting on some simple recurring concepts: locks and keys, treasure chests and checkpoints, gates that won't open till all enemies nearby are slain. Many of them also harbour a boss whose defeat yields a Top Trumps-style collectible card you'll use to expand your Dust storage facilities and progress the story. Like Kirby, Nova can hoover up hostile critters, which range from Dragon Questy slimes to exploding kamikaze snowmen, and spit them out as projectiles to destroy otherwise indestructible threats or interact with out-of-reach objects.

From these bare beginnings, Anodyne 2 finds its way to some ingenious and startling places. There's a vast spectrum of tones and genre precedents in play: one moment you're roving a vaguely solarpunk apartment complex, fetching commissions for a fashion designer, the next you're adrift on a sugar-pink purgatorial ocean redolent of both Dark Souls 2's Majula and Spirited Away. Some dungeons hinge on a particular puzzle gimmick: a mad science lab, for example, in which another character mirrors your movements in a neighbouring room. Other setups are more grandiose: there's a medieval fantasy kingdom with a delightful faux-Beethoven score (the game's soundtrack in general is sublime), where you'll quest for pieces of magic armour to un-petrify a prince.

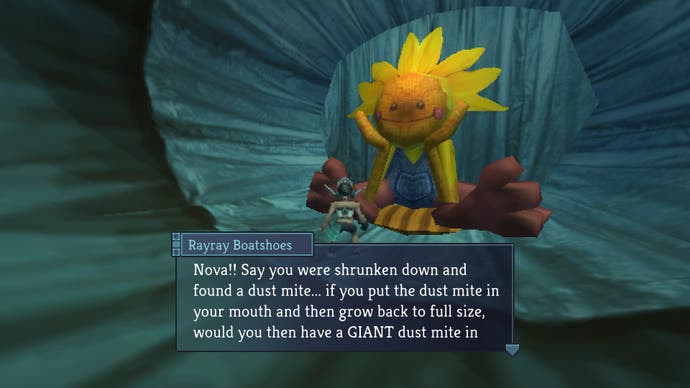

As Anodyne 2 evolves, it puts its own two-world structure under pressure. Sometimes, travelling through a person's psyche takes you somewhere else in the overworld. On reaching a certain area, you also gain the ability to travel inside creatures inside other creatures, winding back the game's art direction still further, from 8-bit consoles to the days of the ColecoVision. These formal explorations are of a piece with the whimsy and relentless, bruising self-referentiality of the writing, which calls to mind the artier variety of leftist Twitter feed. There are jokes about, for example, whether the Ancient Greeks painted their statues, and Shakespearean jesters seldom being as foolish as they appear. There is a surprising abundance of poetry, from free associative verse in database entries (consider: "Bicalutadmide tricks and porridge twicks, snap the marketing research into delectable crisplings") to the kind of breathy, bloody love plaints you get at open mic nights in London's East End.

Above all, though, there are countless jokes about videogames, including gags about 2D staircase tiles and the convention of darkening the screen during an inner monologue. Many of these send-ups are throwaway, but some of them have a larger purpose. There's an unlock later on, for example, which parodies corporate cults of innovation by subverting the classic mid-campaign gambit of adding collectibles to restore interest in a well-travelled world. The whimsy can be exhausting, but I never found it gratuitous - partly thanks to the sheer imaginativeness and often celebratory quality of the jokes, and partly because there is a poignancy to everything that cuts through Anodyne 2's cynicism.

This isn't "breaking the fourth wall" - it's not the complacent self-own of the blockbuster sequel gesturing to the hollowness of its conventions. The gags, together with the miniaturised stories about community and family that often frame them, are a means of defence against an uncaring universe. They are both consolations and ways of expressing anger, fear and sadness. This goes hand in hand with an understanding that the rules that comprise games (including those of Anodyne 2) are social scripts, a means of comprehending our relationship to other people and environments. As one character puts it at a critical plot juncture, "a card has power only if we all agree to its rules". To joke about those rules, then, is to offer up the associated social practices for reinvention.

The value of indie period recreations like Anodyne 2 is partly how they resist the chronology of obsolescence laid down by videogame hardware manufacturers. They might harken back, but they don't do so out of mere nostalgia. They are assertions of the validity of aesthetics and methods of structuring and interacting with a world we have been trained to perceive as outmoded - save, of course, for when we're being asked to pay through the nose for a remaster. Anodyne 2 suggests an artform coming into the fullness of its own expression, free to adopt techniques as needed to say something worth saying, without worrying about whether it looks "new enough" or conforms to genre expectations. It harkens back in order to look forward, sideways and within.