Arcadeware - A Glance Through The Coin Door Of History

Silicon beneath the surface.

The technology of our home systems is an open book, and one we always read thoroughly before making a decision on which machine to pour our thick, syrupy love and devotion upon. But arcades games had the unique fortune of being judged solely on the quality of their games, rather than the silicon that drove them. So let's take a look behind the coin door and see what electronic wonderlands could be found in yesteryear's arcade machines.

There are many among our bustling retro ranks that pride themselves on a grand understanding of arcade PCB's, wiring looms, control panels and power supplies, but the current climate of our emulation nation negates the necessity for such an expertise.

The truth is, more people are likely to tinker in the chest cavity of an arcade upright or the brain pan of cocktail cabinet because they're building a MAME cab, rather than repairing an old coin-op campaigner to its former glory. And, in many ways, it's difficult to argue that a cabinet, monitor and joystick aren't put to better use as an emulation control system rather than a single game museum piece. But as we all know, the retro gaming scene is one of mixed feelings and while we love to play those old games in as convenient a way as possible, we also demand a rigorously high level of authenticity.

So, it seems only fair that we take a brief respite from the ooo-ing and ahhh-ing over an online retro re-release and take a look at the machinery that provided so many hours of thrills and robbed us of so many 10p pieces all those years ago.

Discretion is the better part of valve driven circuitry.

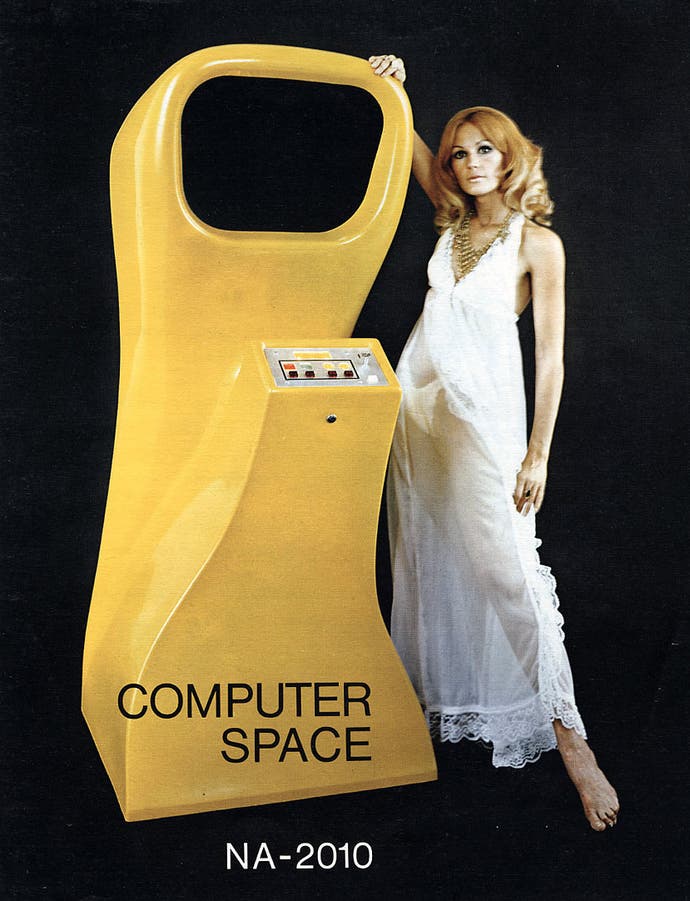

Our quest to uncover the value of an arcade machine's original innards is one which finds immediate purchase; particularly for any avid retro collectors enjoying a recent divorce and the extra floor space matrimonial unshackling brings. The original coin-op created by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, Computer Space, was built like so many game systems during that embryonic age - from discrete components.

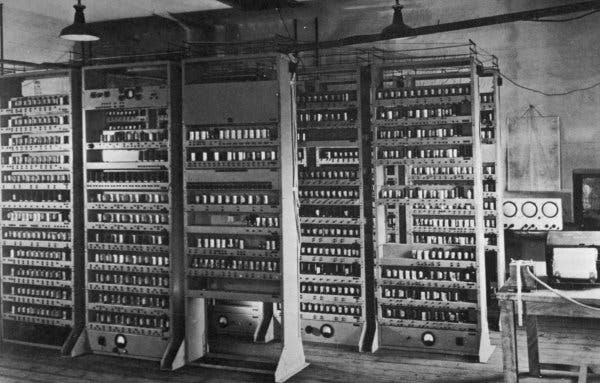

At this point, I should hold up my hand and admit I used to be an electronics engineer (albeit a disinterested and workshy one), so permit me the indulgence of putting a hoof in the nuts of jargon and perhaps bring those who've never interfered with electronics up to speed. "Discrete" electronics are circuits built using individual electronic components (transistors, diodes, capacitors, etc.). Naturally this takes up a lot more room (hence early computers looking like a sales showroom full of fridges) and limits the complexity such handmade silicon parts afford.

But there's a distinct problem discrete circuits bring to the nostalgia hungry retro gamer: they can't be emulated. Emulation - whether on your PC, mobile phone, PSP or MAME cab - relies on recreating the built-in software that ran your favourite arcade machine, but when that game was simply a result of an electron stream trickling through a cleverly designed pathway without any kind of artificial calculation along the way, we're stuck with approximations and mimicry. Therefore, Computer Space - a vital nexus in the history of arcade gaming - exists to this day only within its own fibreglass moulded universe.

In many ways, this makes it extra special (although the game kinda sucks ass), as locating an original machine and attempting to tweak 35-years of attrition from its potentiometers is the only way to recreate that chiffon-soaked scene from Soylent Green (that rhymes, and you know it does). The same goes for Breakout, Death Race and a host of other classic titles, so already we can see the importance of an unplundered arcade machine tomb.

Fortunately Pong came along to change all that, otherwise we'd each need a warehouse to store our game collections. It had a massive impact on the gaming revolution, as you already know, but the grey matter of that bat'n'ball beauty made an equally significant bearing behind the scenes. Including an IC (Integrated Circuit - a "chip" to you and me, which is essentially the same as a discreetly populated circuit board only the components are microscopic and therefore more efficient and in vastly greater numbers) in a videogame was a trivial and frivolous use of such crucial modern technology, but Bushnell's keen business eye saw the benefits from a great distance.

As we can today, since microchip's allowed software to be stored within the cranium of our beloved games - software which can now be surgically removed, cloned and implanted in all manner of new technological consciousnesses. The craze caught on quickly, and before long, the first Pong-on-a-chip device (General Instrument's AY-3-8500 IC, manufactured in Scotland) was being turned out by the thousand, providing the raw game mechanics for literally hundreds - if not thousands - of home and arcade variants on the electronic bat'n'ball theme.

This silent revolution was only noticed by the coin-heavy public by way of new and exciting games, though few gave a toss as to what manner of elastic-trickery was actually crafting these digital works of art. One fed the other, and as punters poured a cascade of silver into the games, developers shovelled profits into increasingly advanced technology and bigger, better titles. But there was a link in this chain that stretched and weakened every time another chip was added to the increasingly silicon-packed circuit boards: the arcade owner.