Arcadeware - A Glance Through The Coin Door Of History pt. 2

Silicon beneath the surface.

Grey areas

While it's not particularly apparent to the gamer on the street, most of the big companies have attempted to bring the two distant realms of videogaming - the arcade and home console - closer together. Easily the most famous of these (and closest to achieving this holy grail of videogame systems) was SNK's much lauded Neo Geo console. Incorporating a system practically identical to Capcom's CPS-1 concept (only with considerably more flexible hardware), arcade addicts and the richest of the rich kids could play the same games by the coin, or by the TV.

In 1994, Capcom attempted to compete directly with the high-end Neo Geo, and its CPS Changer system was released. Although the "CPS" part shouldn't be confused with the actual arcade hardware from a few years hence, the concept was essentially the same - arcade comparable games (in both quality and price) for your front room. The Changer system could only really be categorised as a failure, but the principle behind it and JAMMA compatible technology were sound, and had the gaming tastes not shifted toward in-depth home computer titles, Capcom might still have been a hardware contender today. It's also the reason the CPS Changer is such a collector's commodity today, so keep an eye out for a tasty, "R@RE" catch.

This attempted bridging of the two gaming worlds wasn't unidirectional, of course. During the mid '80s Nintendo attempted, quite successfully, to put its extensive NES development to coin-fishing good use. The PlayChoice-10 was an attempt to reinvigorate the arcades by changing the way gamers paid for their entertainment, yet it also adopted the advice previously bestowed upon the entire industry by JAMMA.

These arcade machines housed a modified version of the console hardware which contained ten (equally modified) NES games. Instead of buying three lives, a credit would get gamers a set amount of time in which they could play any of the ten built-in games as many times as they liked. For a short while, this alternative method of buying time at an arcade machine proved popular (particularly in the fading light of American videogames) and took another step toward finding the nexus between domestic and commercial game systems.

Of all the game companies, however, Sega has remained consistently devoted to a cross-industry philosophy - repeatedly forging a middle ground between the two realms when creating its games.

Empire of the ages

The Model 1 hardware was designed with the help of a team that would become aerospace manufacturer, Lockheed Martin. The test software for this new 3D capable architecture - a formula one racing simulation - proved so popular with Sega employees it was released as Virtua Racing in 1992, and the extra dimensional revolution began. Game developers had dabbled on and off with three dimensional graphics for a long number of years, but up until this point none had known such realistic gameplay as the newly christened "Virtua" series. With the addition of Virtua Fighter to the Model 1's limited catalogue, 3D arcade games were proven effective in inside of a year, and 2D graphics became an unacceptable expense to the addicted gamer.

Being prohibitively expensive, the Model 1 system brought very few games to the arcade, but its purpose as a field test for the viability of 3D development and investment had been a resounding success, and the Model 2 quickly followed in 1993 to become one of the most popular and exciting pieces of arcade hardware ever seen.

With no less than five graphics processors squeezed into its sophisticated frame, the Model 2 could shift 300,000 polygons around the screen at lightening fast speeds, and the sudden scope for 3D games became a tremendous enticement for game developers. Immediate classics flooded from Sega and repeatedly dazzled gamers with not only their unbelievable graphics, but their unparalleled ingenuity and superior gameplay. Virtua Fighter 2, Virtua Cop, House of the Dead, Fighting Vipers, Manx TT Superbike and one of the highest grossing arcade games of all time, Daytona USA, were all a result of the Model 2's outstanding abilities.

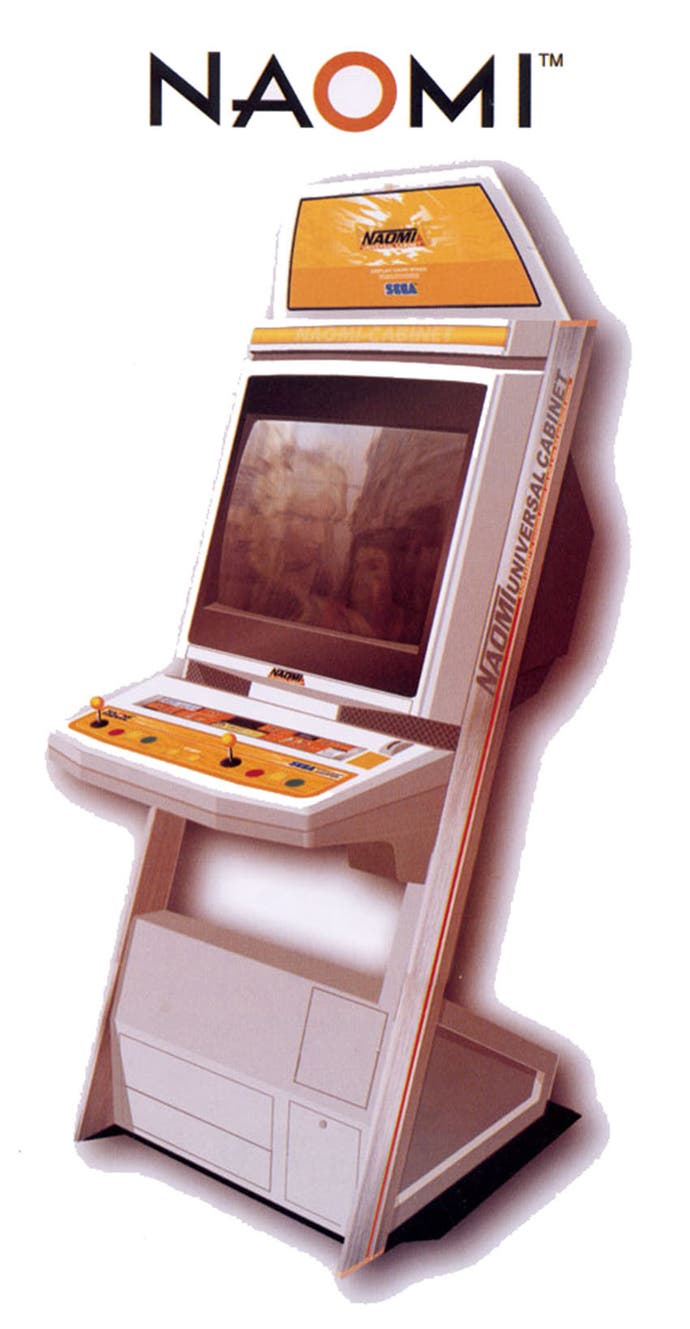

While Sega never followed Capcom's or SNK's lead in trying to bring hardware of this calibre into people's homes, it did revive Nintendo's concept of using console technology to power arcade games. Despite its cult status, the Dreamcast console never survived the stiff competition in the home market, though its arcade based sister, NAOMI (a tenuous abbreviation of New Arcade Operation Machine Idea - although it's also a rather fitting Japanese name meaning "supreme beauty"), saw a significantly more prestigious lifestyle.

Essentially the same hardware as the ill-fated console (only with lots of extra memory), NAOMI is just as well remembered for making a bold move to remodel the tired shape of arcade cabinets as it was for the games it carried. The sleek, skeletal design and inherent adaptability of the system which took a great many pointers from JAMMA (and was even released through the Association's official channels) made it the perfect platform for the new age of three dimensional graphics.

But after so many years in development, Sega wanted to make sure it capitalised on the NAOMI project fully, and employed a mass production system to bring the cost of the hardware to an absolute minimum before licensing it out to third party designers. NAOMI was the closest machine to ever become an industry-based console system, with its raw processing power and extreme flexibility making it the longest running arcade platform ever used. And since the control boards were capable of being cascaded (with enough room inside the saucy NAOMI Universal Cabinet for up to 16 parallel processing boards), the technology has remained capable to the present day and is still seeing new games being produced.

As we look back over the rhyme and reason for success and failure in the arcades, it seems inevitable that the system will continuously unbalance itself. Software is what attracts the gamers and their trousers full of loose change, but it's the constant struggle to develop, maintain and afford the hardware that delivers that vital code. At times, this remarkable hardware has been in too short supply and we, the players, have queued for ridiculous lengths of time for a few minutes of rasterised indulgence, while at other times the sheer scale and complexity of a dedicated cabinet has left no room inside the arcade for the seasoned gamer.

Even now, however, rumours bubble beneath the surface of this fraught industry about Xbox 360 powered arcade machines and though we might be suffering the longest, driest famine ever seen in the commercial videogame world, the turbulent and fickle history of arcade hardware proves it can all change with a bit of well applied silicon.