Are loot boxes gambling?

Crate escape.

Sin City is the global capital of gambling. Casinos with colourful chips, well-postured croupiers and automaton pensioners plugged into slot machines. At first glance it might not seem sinister, but strip back the glamour and Las Vegas paints a sad picture - its denizens cogs in a billion-dollar machine fuelled by potentially addictive gaming. The novelty of the place can hide its true intentions.

That seediness might be hard to detect on the surface of many video games, but replace the roulette table with a Candy Crush wheel and the similarities become clearer. Think about how many times you've paid real-life money in a game for the chance to win an item you really wanted. Was it a nice Overwatch skin? Perhaps it was a coveted Hearthstone card. How many times did you not get the item you wanted, then immediately bought in for another chance to hit the big time?

Loot boxes are a virtual game of chance, but should this commonplace in-game feature now be considered real-life gambling?

Loot boxes have been shrouded in controversy ever since they started popping up in our favourite games: FIFA Ultimate Team, Team Fortress 2, Overwatch, the list goes on and on. Whether you know them as chests, crates or card packs, they ultimately serve the same purpose - loot boxes require you to pay real-life money in exchange for a randomised item. Some items improve in-game performance, while others are merely cosmetic. Either way your chance to get something rare is minimal, and it's likely you'll be encouraged to dip in again and again and again.

While some accuse publishers of money-grabbing by forcing loot boxes into video games, others feel they provide an unfair advantage, which is perhaps more troubling. Take Shadow of War for example. When Warner Bros announced in August the action adventure would feature time-saving loot chests that have the chance to contain XP and gear and orcs, fans reacted in anger. Who wants to shell out more cash on a video game that already costs at least £40?

Other players, and Warner Bros itself, argued the loot boxes were merely an option - you don't have to buy them if you don't want to. But is it really that simple?

Like real-life gambling, loot boxes appeal to our deep psychological need for reward. Psychologist and behaviourist B.F. Skinner researched something called the variable ratio schedule, a reward system typically used by casinos, which sees a person rewarded at varying times. So, if someone does a positive behaviour, such as buying a loot box and opening it, they could be rewarded the first time. They're then not rewarded again until the sixth box they buy, then the third after that, then the 10th and so on.

"Whenever you open [a loot box], you may get something awesome (or you may get trash)," video game psychologist and author Jamie Madigan says. "This randomness taps into some of the very fundamental ways our brains work when trying to predict whether or not a good thing will happen.

"We are particularly excited by unexpected pleasures like a patch of wild berries or an epic skin for our character. This is because our brains are trying to pay attention to and trying to figure out such awesome rewards. But unlike in the real world, these rewards can be completely random (or close enough not to matter) and we can't predict randomness. But the reward system in your brain doesn't know that."

Skinner found this schedule resulted in people performing the positive behaviour more than any other schedule, even when rewards were no longer being given. This technique sounds familiar to the probability ratio in loot boxes. If developers are implementing this 'schedule' on players, does that mean they are using this psychological trick to prey on our psyche and encourage us to buy loot boxes, much like casinos do with gamblers?

Though casinos and loot boxes are technically similar, there is one major difference - a casino can leave you empty handed, while you're guaranteed to get something out of a video game loot box.

"Buying [loot boxes] puts them into the same category of packs of Pokémon cards or baseball cards," says Madigan. "Unlike gambling in a casino, you're going to get something out of that pack. Maybe just not the thing you wanted."

Madigan makes an interesting point; why haven't we had this same debate over Pokémon cards, football stickers, Yu-Gi-Oh cards, Pogs or Kinder Eggs? They work the same: you pay real-life money for the chance to get something you want. Kinder Eggs and football stickers may be cosmetic, but having better Yu-Gi-Oh or Pokémon cards gives you a competitive edge on your opponent. So what makes loot boxes potentially akin to real-life gambling, and these items not?

Dr Mark Griffiths, Professor of behavioural addiction at Nottingham Trent University, has no illusions about the debate surrounding loot boxes.

"Loot box systems are gambling in my view," Griffiths says. Griffiths penned an academic paper that explores whether RuneScape's Squeal of Fortune and Treasure Hunter features should be considered gambling. He arrived at an unequivocal yes, not just because the mini-games meet the criteria for gambling set out in the Gambling Act of 2005, but because the bonds won from these mini-games have value outside of the game. (UPDATE: a representative from Jagex contacted Eurogamer to say these bonds can no longer be used for real-life services. Instead they can be used to purchase membership to the game itself. We've asked why this change was made and will update when Jagex responds.)

So why hasn't any authority called Jagex - or any other video game publisher or developer whose game includes loot boxes - out for encouraging gambling? Why hasn't a regulatory body placed an appropriate age-rating on these games?

Eurogamer asked the Gambling Commission whether it was looking into the issue of gambling and loot boxes in video games. We were told "esports and digital currencies have been a significant focus for us in recent years", with a spokesperson directing us towards a position paper published in March titled "Virtual currencies, esports and social casino gaming" - specifically, paragraphs 3.17, 3.18 and 3.20.

Currently, the Gambling Commission does not class loot boxes as gambling because, in its view, the items obtained from them cannot be exchanged for real-life money. This is an odd position, considering the vast number of third-party sites that let you trade in-game items or currency for real-money. Paragraph 3.17 of the position paper states: "Where there are readily accessible opportunities to cash in or exchange those awarded in-game items for money or money's worth those elements of the game are likely to be considered licensable gambling activities."

Paragraph 3.17 then goes on to describe loot boxes quite explicitly and compares them to playing a slot machine - though they still aren't gambling.

"By way of example, one commonly used method for players to acquire in-game items is through the purchase of keys from the game's publisher to unlock 'crates', 'cases' or 'bundles' which contain an unknown quantity and value of in-game items as a prize. The payment of a stake (key) for the opportunity to win a prize (in-game items) determined (or presented as determined) at random bears a close resemblance, for instance, to the playing of a gaming machine."

Paragraph 3.18 then clarifies that, even though loot boxes or crates or whatever resemble slot machines, loot boxes are not considered gambling unless they contain items with real-world value: "Where prizes are successfully restricted for use solely within the game, such in-game features would not be licensable gambling."

Luckily for video game publishers, this technicality provides a loophole. There's a reason you can't "cash-out" Steam wallet funds or FIFA Coins, even though you can use those funds to buy more games and in-game items.

Perhaps the most important part of the Gambling Commission's position paper, however, is in paragraph 3.20: "On occasions where serious concern exists under those criteria we are clear that primary responsibility lies with those operating the unlicensed gambling websites. However, we will also liaise with games publishers and/or network operators who may unintentionally be enabling the criminal activity."

In summary, loot boxes are in of themselves not gambling. But as soon as a third-party website gets involved, they are. But who's to blame for this unlicensed gambling? According to the Gambling Commission's position paper, it's the third-party websites who are to blame, but it'll have a quiet word with video game companies "who may unintentionally be enabling the criminal activity". It sounds a lot like the current legislation isn't best-suited for this newfangled video game loot box trend. Perhaps in this case, the law is struggling to keep pace with technology.

In recent months, as the furore around video game loot crates has exacerbated with the likes of Shadow of War, Star Wars Battlefront 2 and Call of Duty: WW2 all coming under fire for their microtransactions, some have called on video game regulators to step in. The organisations who rate video games should attach gambling warnings to these titles, critics say. But it seems unlikely this will happen until gambling authorities change the way they think about loot boxes.

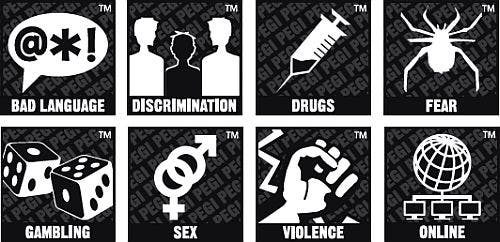

"Loot crates are currently not considered gambling: you always get something when you purchase them, even if it's not what you hoped for," says Dirk Bosmans, from European video game rating organisation PEGI. "For that reason, a loot crate system does not trigger the gambling content descriptor."

PEGI's gambling content descriptor warns players a game "teaches or encourages" gambling. A game gets this descriptor if it contains content that simulates what is considered gambling, or they contain actual gambling with cash payouts. Bosmans doesn't believe the latter exists on the current consoles. As for the former...

"It's not up to PEGI to decide whether something is considered gambling or not - this is defined by national gambling laws,” Bosmans says.

"If something is considered gambling, it needs to follow a very specific set of legislation, which has all kinds of practical consequences for the company that runs it. Therefore, the games that get a PEGI gambling content descriptor either contain content that simulates what is considered gambling or they contain actual gambling with cash payouts.

"If PEGI would label something as gambling while it is not considered as such from a legal point of view, it would mostly create confusion."

The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), which rates games in the US and Canada, echoes PEGI's view. Its stance is loot boxes are not gambling because they guarantee players receive something.

"ESRB does not consider this mechanic to be gambling because the player uses real money to pay for and obtain in-game content," a spokesperson for the ESRB tells Eurogamer.

"The player is always guaranteed to receive something - even if the player doesn't want what is received. Think of it like opening a pack of collectible cards: sometimes you'll get a brand new, rare card, but other times you'll get a pack full of cards you already have.

"That said, ESRB does disclose gambling content should it be present in a game via one of two content descriptors: Simulated Gambling (player can gamble without betting or wagering real cash or currency) and Real Gambling (player can gamble, including betting or wagering real cash or currency). Neither of these apply to loot boxes and similar mechanics."

Ukie, the trade body for the UK's games and interactive entertainment industry, perhaps unsurprisingly supports this position. Ukie CEO Dr Jo Twist tells Eurogamer loot boxes "are already covered by and fully compliant with existing relevant UK regulations".

"The games sector has a history of open and constructive dialogue with regulators, ensuring that games fully comply with UK law and has already discussed similar issues as part of last year's Gambling Commission paper on virtual currencies, esports and social gaming," Twist continues. "The games sector also takes its responsibility to players, particularly children, seriously and employs various parental controls across all devices that can prevent unwanted in game purchases."

It seems PEGI and the ESRB's hands are tied - for now. Bosmans says PEGI is aware of the increasingly vociferous debate surrounding video game loot boxes, and is keeping an eye on developments.

"We are always monitoring such developments and mapping consumer complaints," Bosmans says.

”We see a growing need for information about specific features in games and apps (social interaction, data sharing, digital purchases), but the challenge is that such features are rapidly becoming ubiquitous in the market, yet they still come in very different shapes and sizes."

It seems we have now reached a breaking point in the loot box debate. YouTube, video game websites and forums are alight with complaints and streamers are yelling enough is enough. There's even a petition calling for the UK government to bring in tougher regulations regarding the use of loot boxes in video games. At the time of publication it had over 8500 signatures. 10,000 are needed to trigger a response from government.

But what can be done? Currently, loot boxes are not considered gambling. But the Gambling Commission is taking a closer look at gaming, PEGI is keeping a close eye on the situation and PR disasters around loot boxes are sure to impact video game sales. The wheels are turning on this one. Perhaps it's only a matter of time before the law has a change of heart, and video game developers, mindful of protecting the millions of pounds loot boxes make for their shareholders, will be forced to adapt.

Eurogamer contacted several developers and publishers for comment on the issue of loot boxes. Most failed to respond. Those who did declined to comment. Here's the list: Blizzard, EA DICE, Psyonix, Cygames, Daybreak Games, Bluehole, Jagex, Warner Bros and Valve.