Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes

Can MGS make a decent case this long after the original Shadow Moses incident?

Direct remakes are a peculiar breed. They're not the same as the "re-imagining", a category into which some of the best and worst games of the 21st century have fallen, and yet they're obviously not sequels. With videogame remakes, this oddness is compounded by differing formats, saddling us not only with the worry of whether the game stands up to its progenitor and similar titles of the day, but also the question of who if anybody is likely to buy it, not to mention why? Quite a pickle - albeit in this case a deliciously absorbent one overflowing with the creative juices of gaming luminary Hideo Kojima, and one that cleverly inherits a lot of its sequel's enhancements...

One man's war on terror

Playing through this for the first time though, such questions are clearly unimportant. Far more pressing questions like "who the hell is that blonde guy?", "why is the camera so bleeding awful?" and "eh?" will dominate the mental landscape. Metal Gear Solid, you see, is a game driven or rather dictated by a central yarn about terrorism in Alaska, which gradually unravels as you take control of anti-terrorist extraordinaire Solid Snake and try to infiltrate a nuclear disposal facility, which has been taken over by your former comrades-in-arms and could be used in launching a nuclear weapon. And, put simply, although there's a decent amount of a great game underneath, there's very little point taking the plunge if you're not prepared to watch it as much as you play it.

Back in 1998, MGS was a game unlike almost anything that had come before. It had looks, mechanics and movie-like production values at a time when such things rarely made it into the same box as one another, and since then it has influenced many games in a multitude of different genres. As a result of this its impact today is less groundbreaking than previously, but it's still largely unrivalled in terms of storytelling whimsy, even by enormously cinematic games like latter day Final Fantasy titles. It also remains a distinctly enjoyable yarn about terrorism and genetic manipulation, and perhaps does a better job of tapping into the cultural zeitgeist than it did in those pre-9/11 days, back when we weren't technically "at war" with one issue and arguing with French scientists about the other.

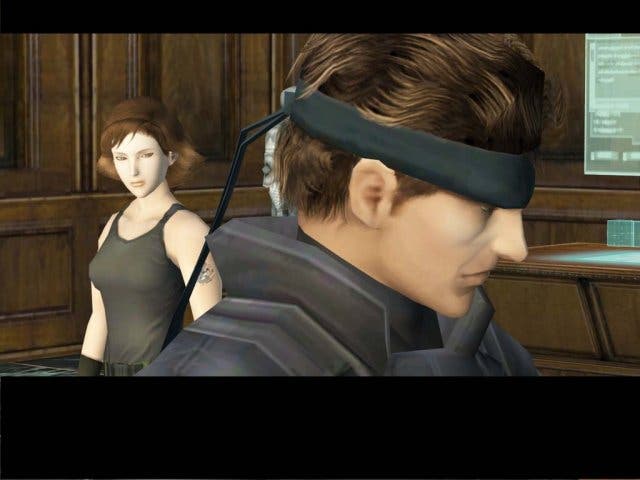

Even at that it's still a hugely enjoyable conspiracy to get involved in, and it's a tale filled with subtlety, borne out over several hours of cut sequences (hence the two disc format) and a great deal of codec conversations (a sort of radio system that all the key players get involved with). It's riddled with moments of genuine and deliberate humour, too - often well delivered by the re-recorded voice acting team - not to mention brimming with more emotive dialogue, and if you allow yourself to be drawn in by it and take it all seriously, it's a reasonably affecting tale about the important things in life and love, rife with clever misdirection and heart-wrenching plot twists.

Son of Sons

Underneath the reams of dialogue and slick presentation though, there is a core game element, much of which will seem very familiar now thanks to the original MGS' success. In other words, it's been pillaged for inspiration by virtually every stealth-action title in recent years, and plenty more besides. But while familiarity may breed contempt, there are still enough moments of genius spread throughout it, and the style, pacing and execution are well worthy of applause even six years later.

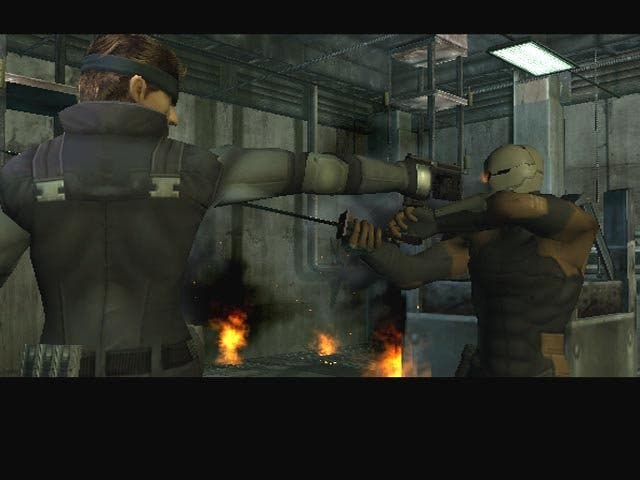

Part of that is down to some degree of inheritance from its younger sibling, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty. Originally Snake was capable of walking, running, crawling, leaning up against and peering round walls, fighting enemies hand-to-hand, sneaking up on them, shooting them from a distance, leaping over a few objects, and utilising a wide variety of high and low-tech gadgets. In the intervening period he's picked up a number of new abilities, and can now tumble into a crawl, target and shoot things in first-person (individual limbs on enemies, cameras, headshots, etc), make use of tranquiliser weapons (and shovel limp bodies into lockers), and hang from rails to evade detection.

With a couple of caveats (the use of digital rather than analogue control for general movement, for example), it's a system that works very well even with only minor refinements, and it means that the body of the work ahead of Solid Snake - sneaking through well-guarded areas without drawing undue attention, for the most part, and scouring the base in search of objectives - can be carried out without encountering too many unreasonable pitfalls. Allowing the player to continue from the last room entered is another decision that stands up today. Less enterprising sadly is the method of portraying the action from room to room.

Stuck in gear

MGS' camera generally frames the action from different static or panning "cinematic" angles that change fluidly as you move around the Alaskan facility. The problem with this system is threefold: one, even with the radar feature activated it means guards sometimes see you before you see them; two, the controls switch fluidly with the angle and this can cause you to lose your sense of which way is up (particularly aggravating when trying to evade things); and three, it means you often accidentally run into inconspicuous edges so that Snake sidles up against them, switching the camera again and sometimes causing you to panic and do something rash or unhelpful. In short, it creates an artificial layer of difficulty, and it's something that ought to have been addressed between 1998 and 2004. It is, after all, a bit much to expect us to continue putting up with a game where you have to guess where a tank is located during one particular section that crops up a couple of hours in.

On the whole though it's bearable, and you won't find yourself moaning about it all that often. Perhaps more upsetting is that for all his gadgets, Snake still can't seem to do more than string a couple of punches together in close quarters. With two key boss fights relying on the hand-to-hand mechanics, you'd think six years might have encouraged Konami, Silicon Knights or any of the other folks involved to change it a bit, but no. The re-shot cut-scenes full of noticeably Matrix-inspired acrobatic combat underline this shortcoming, and even if it's not a major issue it's still a little disappointing.

Then again, he does have a lot of gadgets. Solid Snake is unquestionably a very versatile charge, even by modern standards. Apart from his basic skills, he can also make use of complex tools like infrared goggles and mine detectors, but isn't afraid of relying on low-tech solutions like cigarettes (good for highlighting those IR beams, albeit with health repercussions), boxes for hiding under, and even magazines with raunchy centrefolds to distract guards. The best thing though is that many of Snake's tools and tactics are optional extras - you can quite happily make it through the entire game without holding up a guard to pinch his dog tags, for example, or hanging from a railing, and it's this sort of variety that gives you options in the game's tougher moments, not to mention incentive to replay it in the future.

We can rebuild you...

Fortunately few if any of Snake's enemies are capable of this sort of versatility, even if they do share some things in common with him on one or two levels [wink]. Guards here are generally of one cast, although they don't all dress the same, and like their counterparts in MGS2 they will react to a glimpse of you, a loud noise, or the sight of a fallen comrade. When they come looking they're quite attentive, too, even going so far as to search lockers, boxes and through open doorways if they're actually on alert. On the other hand though, they also fail to follow you through doors that involve a short loading delay, and fail to spot you if you're over a certain distance away in the same room. Granted, these are quirks that you generally appreciate when it comes to making actual progress, since it's often difficult to shed the guards' attention by conventional means, but still we'd be fools not to cite them as some manner of flaw.

Another flaw is the issue of slowdown, which is particularly irritating during the ascent of a communications tower late on and intermittently intrusive elsewhere. On the whole though it's worth it - to look back on the original MGS now is to look upon a rather ugly game, and by dragging the game up to MGS2 standards Silicon Knights has done us all a real favour. Characters are very well modelled, and startlingly believable in cut sequences (even if the facial animation, facial shadowing and, um, "hair mechanics" aren't always up there with the rest of the body), while increased geometry detail, some nice particle weather effects, higher polygon environments and better texturing mean it's a much more enjoyable view of a game that would look hideously low-resolution by modern standards.

Backing up the visuals is an incredibly stirring soundtrack and a range of sound effects and voice acting that cement the game's reputation as a solid example of largely seamless storytelling. The voice acting deserves particular note. It may be a little hammy on occasion (and a couple of minor parts appear to have switched ethnicity since 1998), but characters like Ocelot, Campbell and the inimitable Solid Snake himself continue to sound just right. In a game that delivers as much in hands-off exposition as it does in tangible involvement, strong voice acting makes a big difference.

Tale of two serpents

Perhaps surprisingly though, since the game's release in 1998 its storytelling has become the subject of criticism and even derision from some people, most of whom will complain that it drowns out what is otherwise a very enjoyable game for the sake of revelling in the director's fantasy. That the game is over in between eight and twelve hours the first time through (depending on your skill and the difficulty level, and with only a slightly different ending, some stealth camo gear/bandana/clothing extras to look forward to on replays) perhaps backs that up. But that view doesn't wash with us.

Sure, Metal Gear Solid is not what a lot of people will expect coming to a "stealth-action" game, it's not the sort of game that stands up to repeated play in the same way as something more formulaically brilliant like Splinter Cell, and it is guilty at times of failing to differentiate between key facts and peripheral info during conversations, but there's an old argument that says you wouldn't give a football game to a reviewer who hates sports, and similarly you wouldn't give a Hideo Kojima game to somebody who doesn't enjoy soaking up a good story. If you want to criticise the strength of that story, that's up to you, but it's our job to tell you what we think of it, and we found it engaging, emotional and rewarding, if unabashedly long-winded.

What's more, without Kojima's intractable whimsy we wouldn't get to enjoy the game's key strength: its willingness to play by its own rules. This is no mere game of three levels and then boss fight, or anything of the sort. It isn't afraid of throwing multiple boss fights at you in succession (albeit with a pause to save, natch), of torturing you, or forcing you to change the way you play in order to compensate for lost radar or tools. It's home to some true variety - you'll fight an Indian in a tank, a sniper, a helicopter, and plenty more besides - and some true genius. Psycho Mantis, one of the terrorist ringleaders, seems worthy of particular mention here for offering a genuinely post-modern take on the classic videogame boss encounter (and rejigged somewhat since the PSone days to please existing fans, too).

So, no, we're not going to use this as an opportunity to join the merry bandwagon and lay into Metal Gear Solid for being what it is. Our criticisms are clear and well documented already. Otherwise our only other slight concern is the straightness of the port. While Capcom's Resident Evil remake reworked key sequences to scare you in new ways, often playing on your expectations with a clever bit of misdirection, Twin Snakes does nothing of the sort. That's something newcomers won't have to worry about of course, but old hands may view as a missed opportunity.

Remains Solid

All of which brings us full circle to the question of rating the remake. Newcomers? Buy it if you think you can handle a game that's as much a story as it is a game. It may take you half an hour to pick up (hint: take a chance where Splinter Cell has taught you not to), but it's an experience that you will cherish for a long time to come, full of characters you'll care about and want to follow in the future. Better yet, these are characters you can follow immediately by picking up Metal Gear Solid 2 on PS2 Platinum, or MGS2: Substance.

As for those of you who cherished the original game? This is the best pair of rose-tinted spectacles money can buy, and a good alternative to the anti-climax of seeing how a once-cherished favourite has aged. If you only have a fading memory of the game you once loved, playing The Twin Snakes is akin to watching an old movie and seeing it the way your mind's eye remembers it, complete with technical improvements you couldn't even imagine at the time. It's an experience that we don't often get to appreciate as gamers or otherwise. On the other hand though, it's also another £40 to spend, and that may play a role in making the decision for you, particularly if you have a solid recollection of everything that once unfolded so magically on a tiny little portable TV in your bedroom.

As for us? Well... Let's just say we're content to live for ourselves on this occasion.