Retrospective: Baldur's Gate 1 and 2

Baldungsroman.

I've really set myself up for a fall this time. It's just not that I have to tell you how much the Baldur's Gate games meant, or still mean, to me. It's not just that I have to explain how they're tied to key events in my life, or that even now a single sound, quote or strain of music can still take me back. It's that I have to communicate my depth of feeling without making you think that I am a madman. A crackpot. A total nut.

I bought the first Baldur's Gate on a whim. I was bored and sad and working the most god-awful accounting job that you could imagine, a job where our boss was one of those co-ordinated paperclip neat freaks that we now make office comedies about. Baldur's Gate came in a glossy box, spread across five CD-ROMs and accompanied by that most decadent of luxuries, a fold-out map. It was retail therapy.

I didn't imagine it could live up to its hype. I'd long since lost interest in the PC's role-playing games, which had become either tedious dungeon crawls, spreadsheets of magic items or action-focused bash-'em-ups. Baldur's Gate, I imagined, would be another distraction. Most importantly, it would contain no sums, no invoices and no purchase orders. I was not prepared for it to have an incalculable influence on my life.

A few years of relatively spiritless role-playing meant I knew how the cack-handed 2nd edition Dungeons & Dragons rules worked. I rolled the game's dice. I built a character. Then, I found myself standing outside the door of a Tudor-style inn, the wind brushing the trees and birds singing as the most beautiful music I'd ever heard in a game began to play. I stepped through the doorway. I spoke to the innkeeper.

"MY 'OTEL'S AS CLEAN AS AN ELVEN ARSE," he bellowed.

Everything after that is a blur. I don't remember how many evenings I rushed home to throw myself into that game, to lose myself in its beautiful depths and to let it paint smiles across my face. I was rapt, in awe of its production quality, of its gorgeous rendered backgrounds, its enormous playing area and its seemingly endless hidden treasures. I had never seen a game with such a detailed and yet such an open world, a world where you could literally wander off the beaten track into the whispering, autumnal and often deadly woods.

Adventure was everywhere, with quest treasures begging to be seized, plot threads waiting to be grasped, my travels taking me from the haunted hilltop ruins of a mage school to the wyvern-infested caverns under a forest a-scuttle with giant spiders. It didn't even matter that the central plot was a convoluted introduction to a sinister secret, because it was just one story among so many that this game was waiting to tell me. Baldur's Gate rewarded me every time I exercised my curiosity, showing me that, whether I could handle it or not, adventure was not only waiting for me around every corner, it practically hung in the air like morning mist, so drenched was this world in danger and magic.

Adventure lay at the end of the forest path, was scrawled across the headstones of a forgotten grave, was hidden in a gurgling waterfall, was even found behind the painting on the wall - and the overconfident explorer soon learnt that one misstep could take them through a secret door into the kobold-infested sewers, the opulent tomb of a cursed and long-forgotten sorcerer, or even on to another plane of existence.

Through all this, it sang to me with its sweeping, vibrant soundtrack. By the late 90s, and particularly after Grand Theft Auto and Command & Conquer, I was aware that video game soundtracks were improving no end. But Baldur's Gate was the first I found truly cinematic, with music grand enough to match the game's vision and ambition.

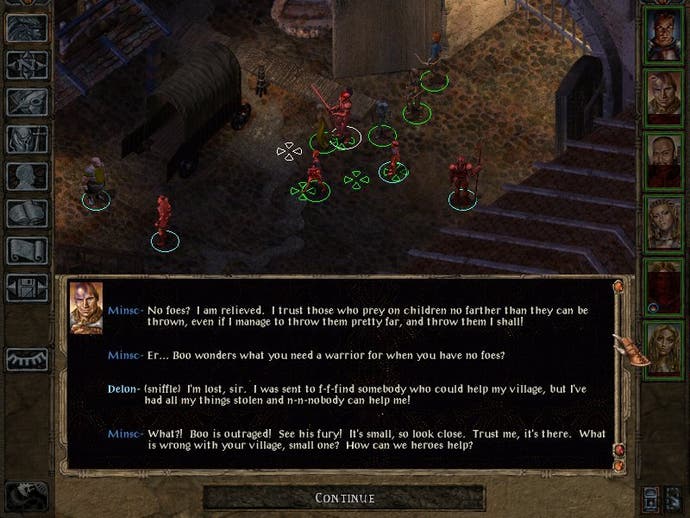

But most memorable was its wit. The time was yet to come when all video game dialogue would be performed by voice actors. The Baldur's Gate games came just before this and, with Planescape Torment, represented not only the last of the text-heavy roleplaying games but also the most literate, demonstrating some of the wisest, savviest and often funniest writing ever seen in any video game.

It was irreverent, referential, self-aware, sarcastic and charming in equal measure, its words animating its characters and world as beautifully as its music and its visuals. It told the stories of embittered slaves, eccentric explorers, half-mad magicians and poor Maple Willow Aspen, who simply wanted to avoid any more tree-related taunts. The game was as full of jokes as it was adventure, its puns and pranks as much a reward as experience points.

My late teens had me trapped in a soul-crushing job in a nowhere town, losing all my friends to universities across the country. It was the toughest time of my life, and sometimes the saddest. My life had stalled when suddenly, thanks to that whim, my imagination was lit up as if by a flamethrower and my creativity returned. By chance, Baldur's Gate also helped me to get to know one of my best friends and it returned me to tabletop roleplaying. As much as any book, it also inspired me to write, even to write about video games professionally. Perhaps most important of all, I think it helped keep me sane. I told you I wasn't a crackpot.

When its sequel arrived two years later I would've been happy with more of the same, but Shadows of Amn was like a fine wine, richer and darker, while even more grandiose in its scope and themes. It took the Dungeons & Dragons formula to its logical conclusion, painting adventuring parties not as wandering heroes for hire but as lonely bands of damaged people who repeatedly witness death and suffer loss, roaming the lands together as rootless, surrogate families. The game's vaunted romances, where non-player characters would grow closer to the player and which prefigured those of Mass Effect or Dragon Age, all told stories of terrible loneliness and hurt, while other characters carried forth from the first Baldur's Gate had also suffered great harm.

The game was as much a coming-of-age story as it was an adventure. Both the player and their companions gradually came to understand the true nature of the protagonist, someone wrestling with a growing awareness of their heritage and with a fear of what they might become, even how they might harm those few close to them, their fellow travellers. Mirroring this, its environments became ever more sordid and unpleasant. Its cities were grittier, its crypts murkier - and, eventually, it took its players into the fabled Underdark and even the many hells themselves, regions where it became all too easy to feel at home.

It wasn't simply that these locations were more dangerous, it was that they were darker, grimmer and had ever more sinister implications. They were a metaphor for your own descent into the darkness within and a far cry from the first game's pastoral, romantic and homely beginning. All this coming of age, with its discussion of power and responsibility (and clumsy romance), was oddly familiar to a young man coming to the end of his teens (and united with his girlfriend of the time by a love of the first Baldur's Gate).

And if the first game inspired me, the second overwhelmed me. It outclassed its predecessor in every aspect, making its locations larger, its writing sharper and funnier, and adding an astonishing amount of content ranging from countless bizarre creatures to talking swords to a whole, richly detailed, you-might-not-even-go-there underwater city. My adventuring party became more animate and articulate, reacting to me, to each other, to the world about them, and doing so with the voices of accomplished actors that included David Warner.

Warner dominates what is not only my favourite moment in the game, but my favourite in any since. A guided tour of a spellcaster's asylum, a haven for the magically afflicted, is almost one long, indulgent and interactive cut-scene. As you and your party walk from cell to cell, being introduced to every inmate by a stern and indifferent Warner, the game presents an increasingly bizarre cavalcade of characters, each more affected than the last. A small girl claims she can change shape and also see behind the "masks" that others wear. A mentally unstable woman sees the true nature of reality and, for one terrifying moment, reveals it all to you.

While Baldur's Gate set my inspiration alight, its sequel forever changed the way I looked at roleplaying games, at the characters within them, at how they do (or don't) solve their problems. At the climax of Baldur's Gate 2, my adventuring party took a moment to speak with me, to reflect on all that we'd done together and to tell me how they felt about me. It caught me entirely off-guard, a moving moment with a horrible sense of finality, as if I'd never have another chance to speak with my companions again. No video game had ever engaged me like this before.

No games since have made me search as hard, laugh as much or feel quite so spoiled, and I like to think they may still have one or two stories left for me. To this day, I'm still delighted to tell the tale of the moment that Baldur's Gate 2 suddenly and dramatically broke the fourth wall with the arrival of the stereotypically teenage adventuring party of Tim Goldenhand. Those bickering, fledgling adventurers, speaking as if sat around a table role-playing, concocted the most naïve and telegraphed attempt to betray my character before, without warning, reloading the game to undo their failure. Yes, reloading.

Some might say that BioWare has come far in the last 12years, that the Baldur's Gate series was a splendid role-playing debut - but I don't think the studio ever left those games behind. They've become the foundation upon which all its other titles have been built and their influence still echoes down the years. For me, BioWare's best work is that which most closely reflects its first two role-playing games - and it has failed somewhat wherever it has strayed from them.