How the Amnesia sequel's sausage was made

Jeffrey goes in-depth with A Machine For Pigs' scribe Dan Pinchbeck.

You may not know Dan Pinchbeck by name, but chances are you've heard of some of his games. The British indie developer made waves in the industry a few years back with his experimental Half-Life 2 mod, Dear Esther - a project Pinchbeck and his company The Chinese Room remade as a standalone release last year - and more recently he headed development on the divisive Amnesia sequel A Machine For Pigs. The Chinese Room's games are often characterised by their arcane prose, abstract storytelling, and an almost complete lack of conventional game mechanics.

It would be easy to imagine Pinchbeck as a snooty artiste. Instead, it may surprise you to learn than Pinchbeck is an extraordinarily approachable, modest man who put 170 hours into Just Cause 2 and argues that Doom is an under-appreciated gem of video game storytelling.

Speaking to Pinchbeck over Skype, it's impossible to bring up A Machine For Pigs without first discussing its most criticised aspect: it's simply not as scary as its predecessor, Amnesia: The Dark Descent. Why's that the case? Many of Pigs' harshest critics have attributed this to The Chinese Room nixing the first game's sanity mechanic that caused your character's vision to get blurry and imaginary cockroaches to crawl over your face and make skittering, crunching sounds in the back of your skull when gazing upon an enemy or staying in the dark for too long.

As it turns out, Pinchbeck was originally planning to introduce a new variant of this mechanic based around disease, but ultimately felt like players would inevitably find a way to exploit it - just as they did the first game's sanity mechanic. "When I was playing The Dark Descent, I figured out you could exploit the sanity mechanic pretty easily, and then it stopped being something that had a real function in terms of the experience I was having. It seemed like quite a lot of people shared that sort of feeling about it," Pinchbeck explains.

"When we first started making the game we were kind of looking at this and we originally had this other idea, a very early thing where it was all sort of based around infection and disease and rot and you were trying to find medicines to stay sane. But when we kept doing this we talked a lot about it with Thomas [Grip] and Jens [Nilsson] at Frictional, and we felt like we were pushing the player out of the world and into a different space where they were just worrying about their supplies. A key thing about this game is about that sense of immersion. If we're doing anything that's essentially damaging that, then we ought to not be putting it in there."

Despite this minimalist design philosophy, Pinchbeck maintains that he likes mechanics-based games, but only if the mechanics are justified. "We've been misinterpreted a bit recently as being this rabidly anti-mechanics company. It's not that," Pinchbeck states. "Initially it was a more mechanics-driven game. It really was a long conversation in the team and with Frictional as well kind of going back to scratch and going 'Well, why are they there?' [If] we can't really answer that question in a way which makes sense in terms of the overall player experience, then they probably shouldn't be there."

Okay, I tell him, but there wasn't much to take the place of these stripped out mechanics, which ultimately resulted in a less scary game.

Pinchbeck doesn't argue with this notion. "It's an easier game. There's no question about it," he says. "When we first started making it, it started off in this status where it was much more difficult. The puzzles were more obtuse, there were more enemies. There were maze sections in there originally."

So why scale it back? It's a complicated process of decisions that led to this conclusion, but the short answer is that Pinchbeck's main priority was for players to actually finish the game, something most didn't with its predecessor. "We really wanted to tell a story in A Machine For Pigs."

"The immediate problem is that if you really want to tell a complete story, and you want to get as many people through to the end of that story, then there's a massive contradiction. Because every time you do something that is really, really terrifying you lose a bunch of players. We knew that from looking at how The Dark Descent went. The completion on Dark Descent was so massively low."

While Pinchbeck remains extremely proud of his creation, he's also his own worst critic. "Looking back at Pigs, I think Pigs is too easy and too forgiving. It could have been a more difficult game and players would have had probably a bit more of a tolerance for that than perhaps we pitched it," he admits. "It comes down to 'is this game about an experience, or is this game about challenge?' Those are hard questions that you do your best to get right."

"We definitely made the decision that we wanted as many players as possible to make it to the end of this game, and if you make that decision your goal, then it does radiate backwards about the decisions you make about the difficulty of different sections of it. So I kind of defend what we did, but I'm not so arrogant as to say that we got it right 100 per cent of the time. There are places where it could have handled being harder."

"I can kind of hold in my head two or three fairly contradictory interpretations of what might be going on at the end of Pigs at the same time. I really like the idea that players tell their own story."

A Machine for Pigs might not be as terrifying as its predecessors, then, but it's got a mean line in gallows humour. Generally when horror games insert comedy it's of the fourth wall breaking, easter egg variety (something Frictional founder Thomas Grip has criticised in the past), whereas Pigs' comedy is more carefully woven into the horror. "To me it was quite important that there is a kind of black humour running through it. We always said there's this very serious kind of political thing that we're trying to say with this, but this is also sort of Victorian penny-dreadful novel. This is pulp. This is a game about a monstrous clockwork AI beneath the streets of London with monstrous pigs to do its bidding. You can't take that 100 per cent seriously."

"If it's just constant awful oppression you kind of get burnt out of that after awhile and you need to have sort of moments of lightness in there where you can kind of just go 'Okay, I can just diffuse a little bit through that," Pinchbeck hypothesises. "There's a little sign up by the pig nest basically asking them to stop f****** each other all the time. And it's just kind of really nice. Something like 'work together, sleep alone.' It's so silly, but it's so human."

Pinchbeck actually likens the humour in Pigs to an unlikely source: Austin Powers. "Every single time a goon gets killed it cuts away to the police rolling up outside a condo with like a mother with a baby and the police coming and going 'I'm dearly sorry. Bob didn't make it at work today.' It's such a brilliant kind of gag to have and there's almost sort of an element of that, of just going 'they're more than just pig monsters.' If we could just have a little glimmer of that in there, then something really interesting goes on."

One thing I found fascinating about Pigs was how open-ended its story is. Even after two playthroughs I'm a bit stumped regarding what actually happened in the plot. This is not a bad thing, In fact, Pinchbeck considers this obliqueness a plus. "One of the things that really interests me about writing for games is that games give you this amazing capacity to leave things open and have players tell their own stories, which is kind of what we do on a small scale with most games all the time anyway," Pinchbeck says. "When you play through a level you're kind of creating the story as you go, and it's usually book-ended with very, very, very closed story. You're invited to be incredibly creative and tell your own story, but it sometimes feels like you do all that stuff and then someone turns up at the end of it and snatches the keys out of your hands and goes 'Actually, I'll tell you what's happening.' That can be really disappointing.

"I'm genuinely really, really, really passionate about the idea of saying to people, 'your imagination is as strong as my imagination. You can tell as good a story as I can.'" he adds. "If someone comes out and says 'I've had a good experience and I think this is what's going on,' then every interpretation has equal validity to me. That's something that's really cool and really unique to games... I can kind of hold in my head two or three fairly contradictory interpretations of what might be going on at the end of Pigs at the same time. I really like the idea that players tell their own story."

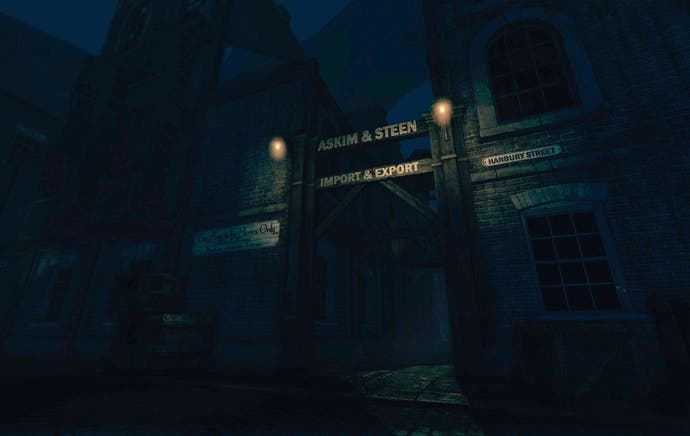

One reason Pigs can get away with its opaque storytelling comprised of scattered notes, sinister phone calls, flashbacks, and text-based journal entries is due to its overall surreal atmosphere. In a game set in a more convincing environment like BioShock's Rapture (or Columbia), it feels out of place to find the exposition stitched across several documents and audio diaries because who would record their innermost thoughts on audio then simply leave them lying around for anyone to find? A Machine of Pigs employs many of the same narrative tools, but its barren nightmarescape filtered through the protagonist's shattered psyche doesn't even attempt to emulate reality, so these typically cliched storytelling mechanics feel right at home with Pigs' extra layer of artifice.

Pinchbeck agrees. "A game is a contract between a studio and a player. You make a deal and you say 'if you take on board this stuff I'm giving you, then I promise you that you'll have a good time," he says. "If you make a game that's very, very story-based [and say] 'these are the rules of this story, these are the rules of this world,' if you do that confidently and honestly, then it doesn't really matter much whether or not the logic maps easily across the real world. Because you're laying out that contract, that position of trust, and saying 'this stuff might happen in this game. It's okay. We know what we're doing.'

"It's partially about projecting that kind of confidence to the players so they go 'Okay, I'm willing to go with you on this.' You're right that it's much easier for horror than with some other stuff, but something like Doom is just brilliant in terms of its storytelling," Pinchbeck states. "Because in its first 30 seconds it goes: 'Just know you're here. Demons are invading a space station.' It kind of goes, 'This is how this game is going to work.' And you don't go 'That's ridiculous!' You go, 'Yeah right, fair enough,' and you buy into it. And that contract is really strong throughout the game."

"Sometimes we get very, very, very caught up on the notion of immersion and saying 'everything is about immersion,' when it's kind of not. Like a game mechanic, it's a tool to achieve a good experience for the player. And sometimes that comes from being incredibly realistic and sometimes it just comes from saying, 'You know what? This is how it's going to be here. Just trust me. And if you trust me, I'll do my best to give you a good time.'"

I find myself in absolute agreement with Pinchbeck here. It's easy to appreciate games that toss living, breathing worlds to the winds to construct a more metaphoric parable. Games like Braid, El Shaddai, and Thomas Was Alone certainly come to mind, but we tend to forget that Doom - with its neon space stations, demonic foes, and glowing green death rays - is just as surreal, its setting just as uniquely tailored to the experience it's attempting to deliver. Pinchbeck seems to realise that even supposedly big, ostensibly stupid games like Doom are actually remarkably sophisticated. It's this potential for interactive storytelling that's led him to games as his medium of choice.

"We're really apologetic as an industry sometimes and we don't really have to be."

"I'm not really interested in writing for another medium at all. It's so exciting writing for games because you can tell different types of stories in a way that you just can't do in another medium. You can look at the stuff we're doing with Pigs, or [Dear] Esther, or Rapture now and go 'you could not realise this apart from in a game.' That's really cool. That's really, really exciting. It's why I get frustrated when people sort of say things like 'We should aspire to be more like this and that.' And I think 'no.' This is an amazing medium to work in because the opportunity for storytelling is so, so exciting."

"There are things that games can do that other mediums are very, very bad at doing," Pinchbeck says. "As a medium it's got real strengths and things that it's weaker at. Every medium has that. You don't go with a film: 'films are inherently not as good as games because films are not as good at implicating you in the action.'... This doesn't make it a weaker medium as a result. It just makes it different. We're really apologetic as an industry sometimes and we don't really have to be."