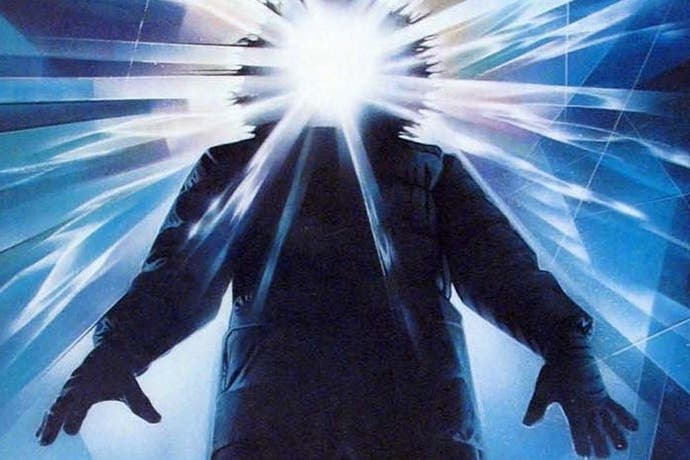

The making of The Thing

Fear knows this place.

The Thing was, and remains, a potentially enthralling, if hazardous, video game license. The movie harnessing a fascinating collection of themes (fear of the unknown, fear of disease and an exploration of man's basic distrust of man) and merging them with a grizzled, yet realistic collection of characters and some suitably nauseating special effects. And it may well have been a box-office flop, but there's no doubting that John Carpenter's film has one of the best cinematic endings ever: exhausted and emotionally drained, the remaining characters, MacCready and Childs, sit within the burning ruins of their Antarctic research station, almost too shot to care whether the other turns into the eponymous creature or not. "Why don't we just... wait here for a little while... see what happens?" mutters MacCready slowly, resigned to whatever fate is in store for him.

Viewers were left to draw their own conclusions, the downbeat denouement suiting the film perfectly. Some 20 years later, with Universal looking to resurrect some of its back-catalogue in order to explore potential videogame adaptations, a more defined answer as to what happened next began to take shape.

British developer Computer Artworks was formed in 1993 by artist William Latham. Joining the company in 1999, specifically to work on the bold mutation-based Evolva, was artist and game designer Andrew Curtis. When Universal began searching for companies to develop their idea of a game based on the cult horror movie, Evolva unsurprisingly caught its eye. "They approached us and asked if we'd like to pitch for the licence," says Curtis, "so we started re-skinning a level of Evolva into an Antarctic base with a freaky thing-beast at the centre. There wasn't much more to it, but it was enough to get the job."

Curtis was soon assigned to lead designing duties with Chris Hadley handling production, Diarmid Campbell lead coding and Joel Smith the lead artist. The initial concept from Universal was clear: the game should continue from the end of the film. "And let's be honest, The Thing's cliff hanger of an ending was too tempting not to explore anyway." smiles Curtis.

Production of The Thing began for real in the winter of 2000 with Computer Artworks compiling some impressive yet challenging design plans. The team gelled from the start and were determined, following Andrew Curtis' lead, to make a game that was not only exciting to play, but also ground-breaking. The first level, set at the scene of the movie's conclusion, was a superb start. "I really liked the way the game began," says Curtis, "as it was all about tension building through environmental storytelling and unveiling the gameplay mechanics." Already aware of how the technology would restrict their open-world plans, the team had devised the exposure meter. Wander too far around the outside of the camp for too long and a bad case of frost bite would soon be the least of your worries.

But despite the movie's genre, The Thing was to be no Resident Evil go-it-alone survival horror. "We always planned The Thing to be more action-horror," says Curtis, "and having had some experience in squad-based gaming with Evolva, it seemed right to have the game as squad-based so we could support the core ideas of fear, trust and infection. It was more about the tension of not knowing what was going to happen next - was the guy next to you gonna try and shoot you, go insane or morph into a freakish beast with thrashing tentacles?"

"When we started working on The Thing, the PlayStation 2 and Xbox had just been launched and I think we made the mistake of believing the hype."

Diarmid Campbell

One of the original ideas was that the player would take every surviving non-player character they encountered to the end of the game. "That was of course very naïve as it caused huge problems with the squad command menu and dynamically balancing the encounters and resources required for the NPC." says Curtis. The compromise the team implemented was to remove certain NPCs at scripted moments and this led to even more complications, as we shall discover shortly.

Meantime, with the design template in place and the script taking shape, coding began. The central idea to the game would be the weaponisation of the thing, with inspiration drawn from movies such as Aliens and Invasion Of The Body Snatchers to other video games (most notably Half-Life), and conspiracy stories such as Area 51.

After a period adapting Evolva's systems to work with the new engine, Diarmid Campbell became lead programmer on The Thing, working hand-in-hand with engine designer and coder Michael Braithwaite. They were both soon battling a complicated concept with the technology of the new consoles The Thing was destined for.

"When we started working on The Thing, the PlayStation 2 and Xbox had just been launched and I think we made the mistake of believing the hype," says Campbell. "And we assumed they could basically do anything we could imagine." The Thing's design allowed for hundreds of man-sized things swarming over the terrain, homing in on the player. "When Michael did some calculations, he said: 'Hmmm, well we might manage three'!" grins Campbell, "And I vaguely remember Andrew Curtis not being particularly impressed..." (We're pretty sure Campbell is euphemising here...)

Nevertheless, most of the features planned by the design team made it into the final game. At the centre was a ground-breaking fear, trust and infection model that was vital if The Thing was to maintain a thematic connection with the movie. Fear was represented by the squad mates' reaction to the conditions around them; lead a nervous soldier into multiple stressful situations or expose him to one blood-spattered wall too many and an unpleasant end was in store for either the unfortunate soldier, the player, or both. "The fear system worked but it was a bit simplistic," remembers Curtis. "Keeping your team sane was a matter of avoiding corpses, blood stains and darkness; but it did produce some great reactions from the squad mates. Some of them were quite rare like the electrocution suicide." Getting your team to trust you was merely a matter of protecting them and/or keeping them well stocked with ammunition; unfortunately the system for infection didn't work quite as well, limited by technology and the template of the game itself.

"NPCs could be infected in battles with the aliens or by being left alone with an infected squad member," explains Curtis, "but sometimes we had to script an infection to remove an NPC from play due to technical and design constraints." Curtis admits this was a 'big mistake' with many players inevitably feeling cheated as fellow soldiers, tested moments earlier and proven genuinely human, could suddenly sprout more tentacles than a Japanese restaurant and attack the player. Diarmid Campbell also recalls the conflicting infection concept.

"The infection system was conceived as a simulation that had the capacity to play out differently each time you played the game, leading to potential replayability. However, the game was also very story-led with set-pieces that required specific characters getting infected at certain times. These two aspects were constantly pulling in different directions. I think we ended up with a slightly messy compromise with good story elements and a genuinely new mechanic but also some logical inconsistencies which, ironically, became glaringly obvious if you played the game more than once."

A simpler and more cohesive technique was the photo-realistic faces that adorned each character. "We just photographed all the development team and then made models out of them," explains Campbell, "so the face textures are just modified versions of the photos we took." As a result, a large section of the development team actually star in the game with Andrew Curtis playing a medic named Falchek and even an uncredited John Carpenter featuring as the scientist Dr Faraday.

Yet despite its faults, a cluttered, unwieldy GUI and a control scheme caught between the past (single-stick control) and the future (twin-stick), The Thing connected with many critics and a significant audience. "Innovation was important to us as a studio," says Curtis, "and we wanted to create a truly unique experience, much like we did with Evolva. I do think many players genuinely engaged with the fear, trust and infection ideas and at the time many NPCs in other games were little more than mobile turrets." Computer Artworks' aims were vindicated when The Thing garnered its fair share of positive reviews, made a decent amount of money and even gained the team a Game Innovation Spotlight award at GDC 2003 in recognition of their outstanding creativity. And they were already contracted to supply a sequel to Universal; good times seemingly lay ahead.

"Some things in it were clunky, excuse the pun, and a bit broken in places, but I think we did enough to keep the fans happy."

Andrew Curtis

"We were very pleased with the game's performance and the majority of the reviews. We all believed we'd created something good, maybe even great." says Curtis. Campbell concurs and adds this about the sequel: "We had the contract in place to make the sequel and were pretty excited about it. We had a very cool prototype of 'dynamic infection' and some really imaginative thing 'burst-outs'. I particularly liked the one where the person would split in half and their top half would jump to the ceiling and start swinging around like an orangutan with his intestines turned into tentacles!" he grins. So it sounds like the sequel would have been awesome - what happened? "It was heart-breaking when Computer Artworks closed but it was a familiar story unfortunately," says Curtis gloomily. "We just grew too quickly, taking on a lot of projects including The Thing 2 and an Alone In The Dark sequel." Sadly, The Thing 2 never progressed much past a proof of concept demo that focused on the team's determination to solve the scripted infection issue.

Notwithstanding The Thing's failings and the closure of Computer Artworks, Andrew Curtis has nothing but fond memories of the time. "I'm immensely proud of the game. It was great fun to make and a lot of the team agree it was one of the best projects they've done. Sure, some things in it were clunky, excuse the pun, and a bit broken in places, but I think we did enough to keep the fans happy and I still meet people today who enjoyed it, which is brilliant!"

Campbell agrees. "When I started work I was a bit of a gaming purist - the mechanics were everything. But I learned with The Thing that characters, story and mood can be just as important. I also learned the value of a strong visionary lead. I found Andrew to be infuriating, stubborn and impossible at times, but I also feel he was most responsible for the success of the game. The Thing is flawed, no doubt, but I'm still incredibly proud of what we achieved."