Final Fight retrospective

Not so fast, Mike.

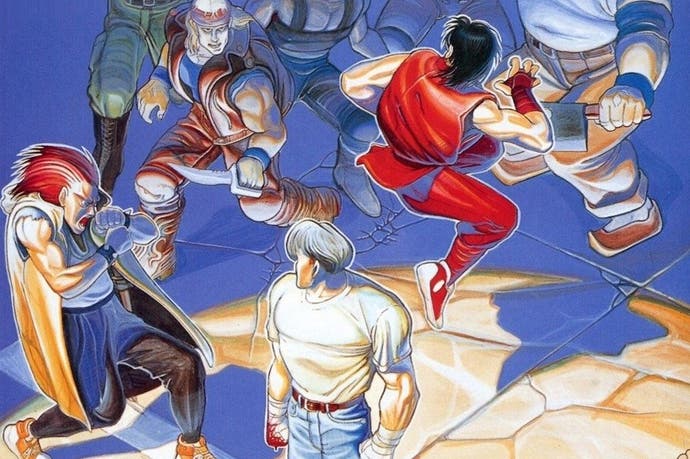

Like so many Capcom classics, Final Fight is a pop-culture archetype, its opening backstreet belt a nostalgic incendiary for arcade goers of the 90s. That distinct credit jingle, those copper rusted oil drums, that telephone booth, that basement warehouse, that beef sirloin inside a pillar of car tyres... and sun-kissed, blonde-dreadlocked Damnd busting through a wooden door and heckling you with his ferocious smoker's cackle.

It's still plain to see why it was ahead of its time. Street Fighter 2 may have guaranteed the fortunes of Capcom, but even in the wake of Makaimura, Bionic Commando and Strider, it was Final Fight that first cemented it as a force to be reckoned with. It was a larger-than-life offering, technically advanced for 1989, visceral and visually supercharged, and, contrary to the complex dynamics of the aforementioned, won audiences by virtue of its relative simplicity and dramatic cinematic qualities.

If you can accept that the scrolling beat-'em-up is married to a specific point in arcade history, Final Fight has barely aged. Ported to just about every console on the map, it's a model for the genre: its sprites bold and beautifully drawn, its collision detection boasting a tautness of unmatched precedent. Competing developers turned out copycat software in droves, but none could match Final Fight's inimitable snap: the feel of its punch volleys and the raw discord expelled from the CPS1's guttural sound chip.

All three characters are uniquely balanced, with experts having put Mike Haggar's cumbersome brawn, Guy's martial art zip, and Cody's tactical strength through rigorous testing. With Guy a good start for novices, the hulky Mayor's strength is a commanding force when governed by specialist handling. Cody's knife-wielding capabilities benefit in close-quarter combat, striking the best all-round balance.

The audio sampling is magnificently heavyweight. Fists whip through thin air like passing subway cars and connecting blows sound like wood cracking beneath the wheels of a lorry. The music is a strong assembly of dark, braying synth over an arrangement of troublesome beats, stressing the game's gritty and violent affectation. Elaborate perhaps, but still one of the arcade's most gratifying aural expositions.

In your bid to save Jessica from the clutches of Belger - the disabled mastermind behind the corrupt Mad Gear gang - you traverse Metro City's trashcan strewn sidewalks and graffiti dyed concrete, a stand-in for the mean streets of 80s New York. Subways, underground fighting arenas, and the now customary mansion infiltration are all present and correct: trends previously established by the likes of Technos' Renegade, but given new life by Capcom's exceptional art division.

The backgrounds and extravagant sprites are rendered with confident brushstrokes and embossed with the kind of vibrant palette work that went on to typify everything the company did thereafter. From the velvety tones of West Side's cosmopolitan backstreets to the rising sun of the Bay Area, it accurately captures the gang warfare vogue of the era.

Above all else, it fits like a glove to play. Our heroes plod forward with purpose, volleys of iron punches locking enemies in brief combos before sending them sailing to the floor. You can flex your dynamic arsenal with intuitive ease, fly-kicking and throwing punks into one another with a rhythmic tempo and a satisfying rumble of bodies. In addition to the various knives, drainpipes and katana that happen to be strewn all over the sidewalk, your basic move set is surprisingly limber.

Jump in with an overhead knee, execute two standing punches into a grab, followed by two knees to the gut and a tidy throw to take out anyone milling behind. Since grab moves deliver heavy damage, it always pays to get in close, but it's down to the player to decipher the threat each enemy poses, their resilience, and how best to handle different group formations. When it all gets too much you can gamble away a small portion of health by unleashing a roaring 360-degree special attack, powerful enough to bat off entire crowds.

For the hardcore player a one-credit run takes a lot of dedication. Capcom, aware of the game's superiority, was also clearly conscientious of its earning potential. Where Double Dragon is a good example of a short, fairly easy beat-'em-up to learn, Final Fight is comparatively drawn out and unrelentingly difficult.

From a business perspective, a compelling and engaging coin-op with highly addictive qualities is the perfect bait, but in today's climate of PCB ownership - that being the original 90s arcade hardware - credit-feeding invisible change is a monotonous and deflating exercise. Compared to earlier stages, where you pound your way through moving train cars, flaming factory gangways, underground fighting dens and rising city lifts, Bay Area and Up Town are static pressure cooker challenges of incoming knives and fists: a war of attrition through acrobatic Poisons, blocking Axls, headbutting G.Oribers and clotheslining Andores. These final two areas become either climactic tests of skill under limited credit conditions, or a tedious grind for indifferent continuers.

Like so many arcade games, Final Fight really only fulfils its potential when properly mastered. By learning to dissect every inch of its six stages, the beauty of its design work comes to the fore. Capcom's cash cow aspirations are partly to blame for it being one of the hardest games in the genre, boasting a strict management system that requires constant herding of enemies and precision strategies on bosses like Sodom and Rolento. It's no mean feat to keep finishing punch combos with over the shoulder throws while being primed for Wong Hoo sprints and Hugo piledrivers - and even then Capcom injects flying knifemen and Molotov cocktail brigades into the mix to really throw a spanner into your organisational strategies.

Those who have snatched a one-credit clear have acknowledged an element of unpredictability, recently admitted by director Akira Nishitani in a tweet as being an intentional random element that produces an "unlucky pattern". Exemplifying this thinking, the final stage is as much a battle against curt business ethics as it is a glorious onslaught of enemies - but there's no doubt its purity endures twenty-three years on.

Beyond mechanical machinations, Final Fight's nostalgic weight is almost equal to its technical accomplishments. Wrecking some poor stranger's car in a sadistic bonus game has never been captured with such award-winning black humour, and kicking a wheelchair-bound man through a skyscraper window remains one of gaming's most poignant examples of political incorrectness.

Whether or not it's a masterpiece or a masterpiece tarnished by heavy-handed commercial enterprising is an eternal dispute. Either way, it still manages to feel like one. In terms of historical value, however, it's priceless.