Somewhere in the multiverse exists a timeline where Mr Do! is as iconic as Mario

Crystal baller.

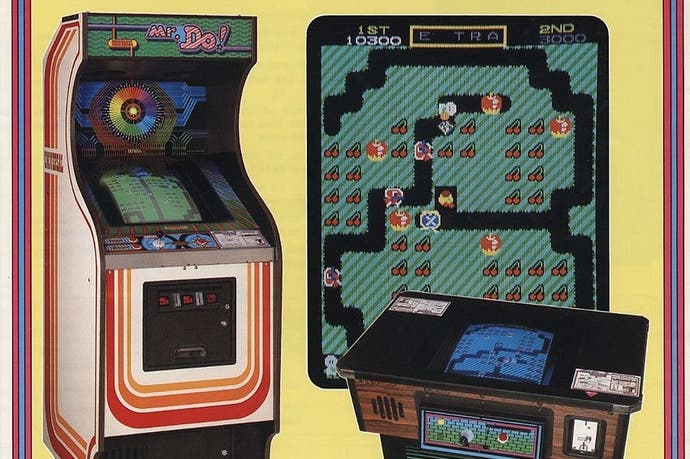

My best friend buys his first arcade machine. Secretly, I'd hoped this might be a mid-life Time Crisis, or at the very least an Operation Wolf. But it's simply a careworn upright cabinet, an entry-level fixer-upper. An eBay description would most likely describe it as "generic", although that doesn't feel like the right word to describe the sweeping, if slightly puckered, blue and yellow side panel art, even if the marquee signage says, simply, "VIDEO GAME". (It's a Ronseal-esque sentiment stealthily undermined by an oversized "O" that resembles the Death Star.) This cabinet looks bashed and slightly battered, its authentic vintage confirmed by a control console designed to accommodate an ashtray. In short, it looks pretty much perfect.

Open it up, turn out the guts and the wiring is a cat's cradle crossed with a dog's breakfast, but it works. The ageing CRT screen may need 10 minutes to warm up before it really gets going but it delivers an appreciable window of optimum clarity. After that, things get warm and fuzzy, but that's not the worst way to relive formative arcade experiences. What is truly special is the ROM that comes pre-installed, a treasure trove of selectable titles from the formative age of coin-ops. It feels rather like a vintage Now! That's What I Call Music compilation, with essential smash hits from the early 1980s bulked out with some intriguing also-rans and nearly-theres. For every Do You Really Want To Hurt Me? there are one or two Happy Talks.

The capstone is the inclusion of Donkey Kong, an opportunity for my friend and I to relive our shared appreciation of The King Of Kong, the remarkable 2007 documentary that quietly adds a Paragon/Renegade metagame to the original title. Now, no matter how you progress on each credit, it seems to ask a moral question of the player: in real life, are you a Wiebe or a Mitchell? For the most part, it feels like I am neither, because I cannot make any substantial headway with Donkey Kong, even with access to more credits than ever before. Twin Galaxies referee Walter Day can put his feet up; there will never be the need to announce a potential kill screen coming up. But this beautiful machine remains a gateway to quality time with Qix, Bombjack, Zaxxon - all holy relics of gaming. Even on a slightly wonky CRT monitor, it feels like a privilege, a luxury.

The game that takes an uncontrollable hold over me is Universal's 1982 hit Mr Do! - and rarely has an embedded exclamation mark seemed so appropriate. The now-defunct Universal were early adopters of remix culture, co-opting elements of Pac-Man and Dig Dug and combining them into something both garish and sublime. Mr Do! is a brave harlequin, often mistaken for a clown, whose name makes him sound like a motivational speaker. He's a proactive agent provocateur armed with a lethal, ricocheting crystal ball, a fearless sapper crawling through a network of deadly tunnels, locked in endless subterranean combat with famished dinosaurs. I previously played carefully cloned versions of Mr Do! on the Commodore 64 and SNES, but he somehow feels more potent, more self-actualised on his native arcade turf, the original gangster of scooping up cherries and pushing golden apples around.

During marathon sessions of arcade Do!-ing, the visuals start to warp and smear, and similar distortions seem to affect parts of my brain. I begin to perceive an alternate timeline where Universal's plucky mascot, not Mario, went on to become the most beloved video game character of all time. In the early 1980s, there was really nothing to separate them - they were both drawn from the same pool of crude pixels, both have-a-go heroes placed in impossible situations. Mr Do! was initially the dude with more agency, allowing the player to choose when to unleash their crystal ball down tunnels for maximum benefit. Mario's automated Donkey Kong barrel-bashing hammer seems clumsy in comparison.

And yet, for all Mr Do!'s inherent vim, it was Mario who would overcome the initial hurdle of not even having his name in the title to become iconic. The forgotten harlequin can perhaps take comfort in the fact that his debut stands up even after three decades. It's a deceptively chirpy collect-em-up with submerged layers of engaging tactical depth. There are at least two ways to complete each screen - tunnel around and collect all the cherries while avoiding dinosaurs, or forget the fruit and focus on defeating your opponents, either by zapping them with your enchanted weapon or crushing them under a golden apple. The crystal ball is powerful but zags off at unpredictable angles. It also operates on a timed recharge that can leave you unexpectedly defenceless during vital confrontations.

As tunnelling progressively opens up the playing area, there's a greater danger of being overwhelmed. But through tactical scoring - or scooping up the treat that materialises in the centre of the screen once all the dinosaurs are deployed - you can trigger a secondary game state. Your opponents are frozen in place, and one of the E X T R A letters from the top of the screen invades the level, preceded by three powerful apple-chomping heralds who zero in on your position. Zap the roaming character and the dinosaurs unfreeze, but you're a letter closer to an extra life.

Collect an entire block of cherries in one unbroken move and, as well as the satisfaction of completing an ascending scale, you claim a bonus score that might be just enough to trigger the other game state. These interlocking mechanics lead to strategising on the fly. Veteran players gauge the optimum time to try and bag an E X T R A letter, and attempt to control the environment through tactical tunnelling and golden apple manipulation. All this is soundtracked by an endless chiptune loop of the Infernal Galop from Jacques Offenbach's 1858 operetta Orpheus In The Underworld. More commonly known as "the can-can", it's an earworm both addictive and infuriating, completely of a piece with Mr Do!'s upbeat outlook.

In the accelerated arcade culture of the 1980s, Mr Do! did go on to head his own mini-empire of titles, including Mr Do's Castle, a platform romp with rickety, moveable ladders that also features on my friend's compilation ROM. It's fun but a little finicky, and lacks the charge of the original. There would be two more Mr Do! games, both unloved, although the durable E X T RA mechanic would recur in Rod Land, the too-cute tale of two fairies repeatedly bodyslamming antagonistic wildlife with their ensnaring wands.

By now, I've played Mr Do! so much, it feels like there are no secrets left. I've even satisfied the bewildering conditions that trigger the random appearance of a special diamond that warps you to the end of the level. I've gone deep enough to discover that there are ten levels that simply repeat. And yet, even though the cabinet is wired up for free-play, there is still one penny left to drop, something that has been staring me in the face for hours. After the first level, each subsequent screen layout is modelled on the number of the level, right up to a big fat zero with a Zorro slash through it for level 10. It's an elegant marriage of form and function that has quietly existed for 30 years without me noticing, belatedly made headsmackingly obvious in one vertiginous moment. That's when I transcend and fully claim my arcade birthright. I am Mr D'oh!