Dino Crisis is Shinji Mikami's forgotten gem

The game that time forgot.

"This isn't a joke, you idiot; we were just attacked by a big-ass lizard!"

It begins with a hair flick - the smallest and most quietly confident of gestures. After four members of an elite special ops team parachute onto a remote island in the fictional Borginian Republic, one turns to camera, pulls off their mask, and with just one toss of her scarlet locks, pronounces herself the heroine of this 90s blockbuster.

While less capable colleagues are being digested, Regina, hand on hip, is dryly quipping over an eviscerated corpse. From that moment on, you're never left in any doubt as to who's running this show.

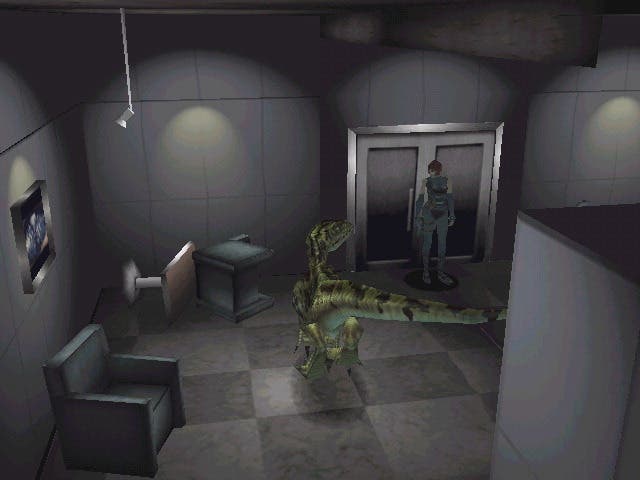

And yet, your very first raptor encounter can take more than eight shots with the 9mm Parabellum. If you try to run, the creature will immediately leap on top of you and try to pull your arm off. Few players walk away from that first encounter unscathed. It's supposed to shake you, literally and figuratively, and it does; anyone expecting enemies like Raccoon City's slow-moving and dim-witted undead won't be so quick to underestimate Ibis Island's usurpers again.

Released in 1999, one year after Resident Evil 2 and just a few months ahead of Resi 3, Dino Crisis' scripting was sharper than that of its creator Shinji Mikami's break-out series, but it was still nonsense, mostly - a toothsome mix of B-movie schlock and sc-fi technobabble. Whilst Resident Evil married a crumbling mansion with a clinical corporate laboratory, Dino Crisis combined future tech with an ancient enemy, selling itself as a 'survival panic' in contrast to Resi's survival horror. Not that Dino Crisis wasn't horrific. The loading screen carried the same warnings for explicit violence and gore that Resi did, but Dino Crisis focused more on maintaining pervasive unease rather than revulsion to keep players on their toes.

The game's signature Danger Events - quick time sequences that result in Regina's insta-death if you don't push enough random buttons quickly enough - exist to work you into a blind panic, reacting to primal instinct alone. These aren't mutilated, mindless, half-decomposed corpses you're dealing with - these are whip-smart, lightning-quick apex predators transported through time yet otherwise perfectly preserved. They don't evoke the kind of terror you feel when looking into the clouded, milky eyes of a bloated corpse, seeing your own mortality staring back at you; rather, these dinosaurs are intended to stir up unease. They're the superior hunters, and far more unpredictable than any zombie.

Whilst the original Resident Evil borrowed its claustrophobic atmosphere and props from classic Gothic horror cinema, Dino Crisis turned to summer blockbusters and adopted gadgets from 90s hacker films for its high-tech aesthetic. This is best illustrated in cutaway scenes with Rick in the facility security room, lit only by the green glow of a computer, his dustpans-for-hands deftly dancing over the keys as he works to decrypt some coded protocol. This style and setting is a clever plot twist in itself; as soon as Regina's government-issued S.O.R.T team (S.T.A.R.S had already taken the cooler acronym) crash land in an island forest, you're expecting some hunter v hunted game to play out amongst the darkened trees. But almost immediately, the action switches to the facility interior - where it's all fluorescent lights, metallic corridors and endlessly escalating tension as your ears strain for the sharp tack of a sickle claw on polished marble tile or gleaming steel grate.

Resi is oddly antiquated in a lot of ways. Jill wears a beret, Barry wears a gilet, the Arklay Mansion is filled with dusty old suits of armour and you grind up common or garden house plants to heal your wounds. Even the puzzles are weirdly totemistic - what kind of police station uses gemstones to lock their doors? By comparison, Dino Crisis is slick and modernised. S.O.R.T wore skin tight spandex. They were colour-co-ordinated. They were weaponised - even the tech guy carried an oversized assault rifle. There was still an emphasis on puzzle-solving, but instead of golden medals and stone plates, problems were themed around matching up electric fuses, rerouting power grids and switching laser gates on and off. Many of the locked doors in the facility use a digital disc key (DDK) system, which requires you to obtain both a code disk and an input disk in order to decode a door's password. And although the idea of using floppy disks and CD-ROMs to open doors is a dated concept now, in a wonderfully backwards way the DDK match-ups actually encouraged players, in the days before smart phones and iPads, to fetch pencil and paper and jot down clues and solutions as they went along.

But for all Dino Crisis' stylistic departures, the underlying mechanics are still unmistakably Resident Evil. The tedious door-opening animations masking chugging loading times are a hand-me-down, as are the cinematic fixed camera angles, the awkward inventory management and the item boxes requiring 'plugs' to access. And it's a happy accident that all these things, as they did in Raccoon City, added to the air of panicked tension. These days it's taken as read that this was the deliberate intention of the game's design, rather than the technical limitations they were actually the product of. That's not to diminish their effectiveness; the fixed camera angles in particular work a treat when there's a dinosaur in the room with you that you can hear but not see. That said, it speaks to the game's sound design that its most memorable audio cue isn't the guttural lowing of a raptor, but the piercing, electronic "doot doot" of the SORT team's pagers.

Unlike the Resident Evil franchise, which has grown, evolved and mutated dramatically away from its survival horror roots, Dino Crisis has, appropriately, been almost frozen in time. A well-received, more action-oriented sequel followed just one year later, but a spectacularly misjudged third entry - an Xbox-only exclusive that promptly rocketed the dinosaurs into future space without any hint of irony - effectively sent the series to the tar pits. The genre as a whole has moved on in some regards since, but there is a revival of sorts underway for horror games that eschew the 'survival action' of later Resident Evils and attempt to capture that early feeling of vulnerability in the face of vastly superior enemies. And, with Mikami himself returning - sans Capcom - to the genre he created with The Evil Within, it could be that one of his lesser known series is long overdue an excavation. It may be only a matter of time before dinosaurs walk the earth again.