David Goldfarb on: Three seasons in game development

"Most likely, you live with them..."

The thought process for the piece was simple enough. Talk about games, I thought. There's so much to say. But everything kept coming out wrong. It felt like something else needed to happen first. Why talk about games if you don't talk about why you talk about games? So I apologize, in the words of Bob Mould, because the following is ruthlessly self-indulgent.

It's still true.

I - Autumn, or Here's How It Starts.

It's 1996 .You're in your late 20s and hoping that any minute now you're going to figure out what you're on this planet to do, because you don't have a goddamn clue.

You've done seven years in three undergraduate institutions and finally have graduated - as bewildered as the day you entered. After a series of short-term stints in a variety of minimum-wage jobs, you've actually booked a trip to Mexico to do who-knows-what. That's when your mother spots an ad in the local newspaper.

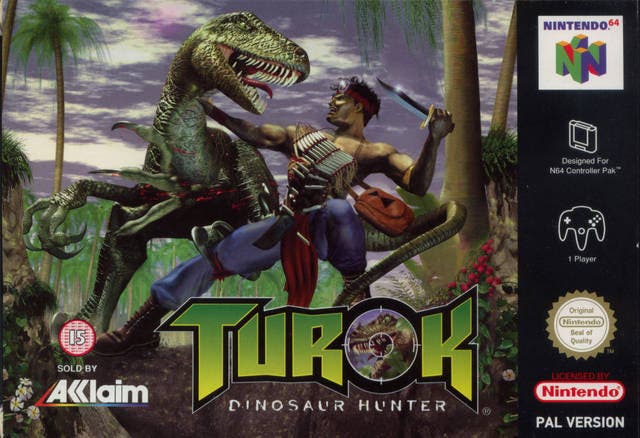

QA Testers Wanted, it says. Acclaim Entertainment. Makers of Mortal Kombat and Turok: Dinosaur Hunter.

Video games? Is that for real? You don't know what a QA tester is and you don't really care. It's video games. The improbability of that career even existing is like discovering a unicorn lives in your backyard.

You've always loved video games. Ever since you were five or so and your father explained how baseball worked and the two of you would talk about numbers and statistics that had meaning and value in a context you barely understood but loved. You collected baseball cards and remembered useless s*** like batting averages and won-loss records and saves. And it was all baseball until you got a little older, saw Star Wars - and found out about video games.

You saw Asteroids for the first time. Hours jamming quarters into a machine: white-hot pixels. All your money gone but you didn't care. Just disappeared into the game. You imagined a day where you'd have all the quarters in the world. To play whenever you wanted. Imagine such a thing! When your dad brought home an Apple II, that was the start of that dream. It was too good to be true.

But as you got older and sank into video games things changed. Did you pull back? It's hard to say. Soon you were trying to play games all the time. Fighting with your parents about how much is too much. And then the war against games was on. You remember your dad hiding the video cable to the monitor to prevent you from playing. You remember thinking how stupid he was and stealing it back. The comedy of this moment eventually leading to a career in games is not yet present.

You drift apart.

Later, games nearly destroyed your college career. Extended sessions of Phantasy Star on the Sega Genesis and late night D&D sessions made you just about the worst student of all time. It was a miracle you ever manage to graduate from school at all given your proclivity for s*** which, for the longest time, you were told was no good for you.

You keep playing video games. Console, PC. You love them. They don't make you whole but they make you forget you're not.

So you call the number and say you're interested. Then you email your resume. These are the days of long waiting. By some miracle you hear back - but they want you to come in the week you're on vacation from your vacation. Back then your interest in games competes with your interest in a woman who is waiting for you in Mexico. You go with the hope that the job is still there when you return, but the expectation that it won't be. It never occurs to you the relationship might follow a similar trajectory until it does. Mexico is not easy.

When you get back you call Acclaim. Come in, they say. You realise you have no idea what a quality assurance tester wears. Although you have never worn a suit in your life to anything, for any reason, desire to make games compels you to put one on. This is patently ridiculous for a QA job but you don't know this yet. In fact you won't have any idea just how ridiculous it is until years later when you have left and your old boss tells you that you were the only person in the history of QA interviews at Acclaim who wore a suit.

You drive 45 minutes to the Glen Cove office and park. It's a big glass building. You aren't even sure if they make the games here or not. Does it matter? It's closer than you were.

Inside are statues of Mortal Kombat heroes, Turok, NBA Jam players. It's hard to explain the feeling you have at this precise point, but terror and excitement are two elements in that emotion cocktail. They take you in for the interview. You're shaking through the whole thing. They're clearly amused.

You get out of there after about an hour. To this day you can't recall what you said or did in there. A few days later you get the call. When can you start? they say. You choke back the word NOW until it feels okay to say it.

II - Summer, 2009.

We've been working on Battlefield Bad Company 2 for a little over a year. It's been a good time, but a very challenging time and we're deep in the long days of finaling the project. Finaling or closing a game has a lot in common with Glengarry Glen Ross. "It's f*** or walk", says Alec Baldwin. You have to Always Be Finishing. This is because as you get closer and closer to shipping a game you need to make more and more decisions that push you toward the goal-line. Good or bad is less important than no decision. Nothing will screw you more than deferring things until the end. It doesn't matter if you've got a great new idea. To use a navigational metaphor, you're out at sea. You wait around for inspiration and, figuratively speaking, who knows if a sea serpent's gonna eat you or a storm's going to blow in and capsize the ship or if you'll just run out of food while you wait and have to eat the crew. And nobody wants to eat the crew. So you make decisions and other people help and you hope to hell they're the right ones and if they aren't you try to fix them if you can. Most likely, you live with them.

Cancer is just part of the world now - as normal as trees and the ocean out there. My father has been sick with leukaemia a long time, over seven years. When I saw him last month we had lots of time to talk about chess and baseball and eat peach pies from eastern Long Island farm-stands. I'd sit on the deck and play a baseball simulation and drink lemonade. It was like being 12 again. Even went fishing. Even though my father has been sick a long time he tells me he's optimistic about his chances. Just the week before he tells me he's planning to start a new run of meds, something he handles more capably than his three oncologists.

It's August and I'm at my desk when a call comes in. It's my sister. "Dad's really not doing well. Maybe you should come home."

But I don't. Not then, and not a few days later when it's clear things have gotten worse. He goes into the hospital and comes out again and for a brief moment we think everything's going to be good, finally. We hoped. But it isn't. And when the end comes it comes in the stupidest way possible. Over the phone.

I have one last conversation with my father. I can barely hear him. It's like the wires carrying our communication are made of paper. I tell him something I hope helps him pass from this world into the next without fear.

You make decisions, you hope they're the right ones. And if they aren't you live with them.

III - Spring, 2010.

You can't sleep because f***ing jet lag sucks, so you lie there and stare at the ceiling until eventually the ceiling turns into daylight.

Later, it's warm and beautiful in San Francisco. It's March 2nd, which happens to be your birthday as well as the release day for Battlefield Bad Company 2. You're there for GDC although it hardly feels like you're anywhere at all because you're so excited the world will get to see the game at last. You remember all the days in the studio. Laughing with the actors toward the end of the project as they made up the most ridiculous ad-libbed conversations. Or playing multiplayer in Arica Harbor for the first time and feeling certain the game was something people were going to dig. You remember how you felt when things were tough too. Days of uncertainty, of self-doubt, of colleagues being smarter, tougher, more insightful than you were. You are grateful they were. You are grateful they are.

You go into a store hoping to spot a copy of the game. It's hard to say why you want to do this but it's probably to convince yourself it's all real.

You find a copy - actually, you find 50 of them. You remember how proud your father was looking at other games you'd worked on. His hand on your shoulder. If he could see this he'd be happy.

Today, as with many days to follow, you choose to believe he can.