David Goldfarb on: The favourite thing

What makes creative people tick?

(Put the needle down on the Replacements record.)

My daughter asked me the other day what my favourite thing to do was. She's at the age where she asks a lot of these questions. I said, after some consideration, "make stuff." Then she asked what was my favourite thing about making stuff, which led to more consideration.

It was a good question.

The What If, I think, is my favourite thing.

A cat seeing a scarf on a windowsill, just out of reach, wonders if its bunched muscles can propel it high enough and far enough to snag the fuzzy trailing strands with one of its claws. Maybe the cat thinks something as formal as, "What if all the cat treats in the world will fall down if I get that scarf?" or maybe not. I'm not a cat telepath. I just see the effect of the process: down comes the scarf, the cat, and any kitchenware unlucky enough to be caught in the chain of feline causation.

In the case of my cat, mischief might masquerade as wonder. I don't know if the cat expects that the 10th time he does this that a magic bag filled with cat treats, sparkly sticks, and catnip pillows will tumble down. Even people are guilty of the same impulses when it comes to the unknown. Humans love to gamble. We love to believe that something amazing is possible at every decision point. We love to believe that a package in Team Fortress 2 is going to have something epic even when we know the odds are slim, that today's the day of our lucky lottery number because it's our birthday, that because the horse in the Belmont had our last name it is a victory sign that we'd be foolish to dismiss. Why else would it happen? Clearly the universe is trying to communicate with us.

Once upon a time early humans asked what would happen if we struck two stones together. Maybe they wanted to make sounds or music. Maybe they were trying to make fire outright. Maybe they were playing a joke on someone with those rocks. Who knows. But somehow, some way: sparks and eventually, flame.

When I start making things usually there are two strategies. Make a list of everything, or ask a bunch of questions and see if they can be answered. Doesn't matter if it's games or stories. Any question will do: what if you add two stones to these other two stones? What if the closet in my room opened up into a snowy wood in another world? What if I was bitten by a radioactive spider and suddenly gained a spider's constitution and abilities? What if the world was made of blocks? What would that mean? What could I do there?

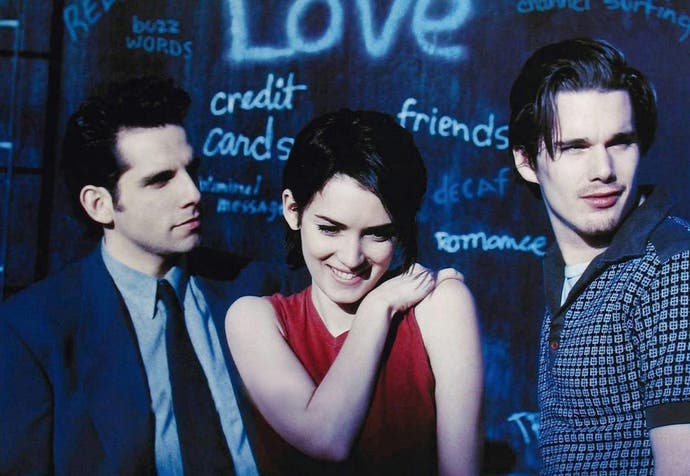

Over time I've come to understand I prefer the question to the list. That's probably because the question is possibility and the list is reality and Reality Bites in comparison to possibility, to reference an old '90s movie with Ethan Hawke.

I love the question. Not just because it's important to games, but because it's important to people. The creative question is an act of joy, more often than not, a hopeful seeing beyond what's here to what's somewhere else. Spaceships, orcs, time travellers, whatever. Sidenote: Elon Musk seems to be pretty good at it these days.

When I was nine or so I had this friend, let's call him Martin. Martin was the kind of kid my teachers charitably referred to as "challenging", and "a handful", and one time when they thought I was out of earshot, "an unbelievable pain in the ass." Martin was a very bright kid. Too bright, in fact. I don't think it was ADD or anything - he just got bored with things that didn't end in literal ruin. Both of his parents worked at the local university as research scientists in some sort of nuclear or theoretical capacity. They had instilled in him their own experimental rigor, especially when it came to prosecuting test subjects with extreme prejudice.

One spring day Martin and I were in his backyard doing something with rocks, probably knocking them together to see if we could build a fire, appropriately enough. We were lousy firestarters though, and nothing was doing besides some bashed fingers and a lot of scraped-up rocks. It was gypsy moth season and this meant the trees were alive with millions of hairy brown and black monstrosities. His backyard was particularly fertile and in the middle was a big birch tree with a gauzy white nest in the fork of the tree. It was full of them. Imagine the pod from Alien seething next to your jungle gym, something so horrifying it was inspirational.

As we stood there idly crushing the heads of stray caterpillars with the tips of our shoes to hear them crack, Martin popped the question.

"What if," he said, "we got those firecrackers my older brother has."

"Uh huh," I said, numbly. "Your brother has firecrackers?"

He nodded. "A whole gross," he said. "Bottle rockets I think. What if we put them in the nest?"

This is the point at which, if you are in future contemplating such action, you want to decline.

However, we were more bloodthirsty than sensible. All our past methods of caterpillar annihilation, while effective, hadn't done anything to stem the invasion. We'd tried everything. Crushing, burning, guillotining with a loop of string. Thinking back on it we probably should have been given some extensive psychological tests by a responsible adult, but it was the late 1970s, so they chalked our murderousness up to 'boys will be boys' and ignored the body count. If we could have waterboarded those caterpillars one by one we probably would have.

"Uh," I said. "What'll that do?"

"I don't know," Martin said, "But don't you want to find out?"

There's a kid's game, forgotten what it's called. Pathfinder or something that rhymed with Pathfinder (Bookbinder? Foeclimber?) but it wasn't.

Here's how you play. Go outside, preferably somewhere you're not likely to stumble into traffic. Close your eyes. Spin around. Then walk until you hit something. The first person to find something cool wins. It's not a good game, but it can be a pretty funny one. Someone's definition of cool was rarely the same as yours. It took multiple iterations, i.e., injuries, to arrive at some kind of coolness consensus. Bottle caps were not cool, but an abandoned Playboy with a bleached centerfold on the cover was. A piece of plastic wasn't cool, but a black poker chip, signifying something more illicit, was. The chance of a broken nose, stubbed toe, or falling down a flight of stairs is improbably high. Why play something so obviously stupid?

Which leads us back to the caterpillars.

Martin came out of his house. He had an armload of bottle rockets, those little blue and red cylinders of paper and gunpowder with a long wooden stick shoved into one side - and something else in his fist.

"Found this too," he said, and held out an oblong thing a little bigger than a shotgun shell, made of red paper tubing, with a thick fuse jutting out of the center.

"It's a cherry bomb," he said with some authority. The high priest of demolitions, was Martin. I nodded in silent admiration.

As it turned out it wasn't a cherry bomb, but its hulking cousin. This was one of the now-very-illegal 50 grams of flash powder quarter-stick of dynamite firecrackers known as an M-80, occasionally called a Blockbuster, made famous in the glorious Jesus Lizard song of the same name.

He wedged it gingerly into the weird tent/hive/thing.

"Stand back," he said, and lit the fuse.

It wasn't far enough.

We had to use a garden hose to wash the What If off ourselves, afterward.