"Almost certain failure": How Monolith saved Mordor

"Don't do a movie game."

It started, fittingly, with the nemesis system, Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor's most interesting design feature, which, perhaps for the first time, brought emergent storytelling to the forefront of a mainstream blockbuster video game. "We were just a tiny skunk-works team to begin with," explains Michael de Plater, design director at Monolith, who joined the studio in December 2010 around the same time the first prototype emerged. "Because we were small we knew that we had to take a systems based approach to the design; we were just not going to be able to compete with other open-world games in terms of scale."

Lord of the Rings is, of course, renowned for its scale. The three novels total almost half a million words, while even the comparatively terse original versions of Peter Jackson's cinematic trilogy plod to a conclusion after no fewer than nine and a half hours. Monolith's challenge was sizeable, even if its team and budget were not: how to create a game based on an expansive myth with a scarcity of resources. "If I had known at the time how hard the development was going to be, I would have predicted almost certain failure," says de Plater. "There were too many hurdles, too many unknowns, too many things we were learning for the first time. But we knew one thing for certain: Don't do a movie game. That never works."

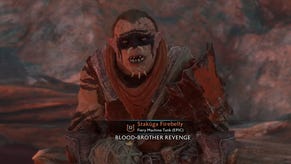

Today, the nemesis system seems like a logical, almost obvious solution to the problem. It divides Sauron's army, who are camped outside Mordor (where the game principally takes place) into ranks of power and seniority. There are officers, generals and grunts and the game reveals the composition of these ranks, allowing you, in the role of Talion, to target specific enemies and create your own dynamic story. As you skulk around Mordor, causing chaos from the shadows, so you disrupt this social ladder. A murder makes room for a promotion, which, in turn, may create a power struggle.

The story, in other words, helps to write itself. "We knew the idea could work but we found it incredibly difficult to communicate," says de Plater. "We needed people to place a great deal of faith in both us and the idea before we could reach the point at which everyone could see that it worked in practice. We often felt insecure about our core system."

Nevertheless, Warner Bros supplied the faith, signing the project and agreeing to allow the team to fully focus on the forthcoming PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, unreleased and unproven consoles at the time. Freed from the need to cater to ageing technologies, Monolith was able to expand its ambition. "We wanted to make the Uruks recognisably different from one another, and use the scars and so on to feed back to the player everything that was happening in the world," says de Plater. "We wanted to have lip-synching and so on. I wish we had been able to commit to next generation platforms right from the start." At the same time, Monolith had shipped its other titles, and Shadow of Mordor became the studio's only project, allowing the team to expand to 150.

The Warner Bros connection proved useful in another way. "We were tremendously inspired by Batman: Arkham Asylum," says de Plater. "It was the gold standard for us of how to approach a license such as Lord of the Rings. It managed to be enormously authentic but also completely distinct from Christopher Nolan's Batman films. Similarly, we didn't want to re-make Peter Jackson's Tolkien movies as games, copy and pasting those storylines. We were fortunate: every stakeholder, including Middle Earth Enterprises and Peter Jackson, agreed with our approach, because Arkham had provided the example of how it could be successful. Arkham provided for us a best practice model both in terms of the design and combat."

As the team replayed Arkham, the idea struck to set the game in Mordor which offered, in de Plater's phrase, the equivalent of "a very large asylum" for Uruks. "It was a location that spoke to the sort of systems we wanted to create," he says. "We wanted to focus on the villains, deep behind enemy lines. We wanted to play with the chaos and factions in turning these guys against each other." While the concept of the nemesis was straightforward, the team struggled for months to find the best way to communicate the shifts in the balance of power between the Uruk ranks. "Everything was a challenge" he says, "The concept is natural, because in so much fiction villains are created in relation to the hero; it makes sense for characters that you run up against to be turned into nemeses. But the problem was the feedback. Initially we had a sports game, team-style presentation, which used character portraits. It didn't work at all. Representing power struggles is hard, and we struggled with how to show promotions and so on. One of the breakthroughs was when we moved away from a menu screen to showing the ranks of the army in full 3D. I'm not saying it's perfect; it was our first go, after all. But being able to see the lines of soldiers, organised by rank made a huge difference."

Shadow of Mordor was a uniquely cross-discipline production. "It was impossible to silo any of the work as every aspect of the game affects every area of the team. For example, a player might set fire to an Uruk in the game. In this scenario the dialogue needs to respond accordingly, with the character complaining: "You burned me!" Then the system also needs to support what's happened, as must the character model, the sound and the animation and so on. It was an advantage to be a relatively small team to make lines of communications easier, but it demanded so much communication between the different disciplines." Eventually, Monolith adopted a flexible seating arrangement, whereby designers, artists and programmers could freely hot desk around the studio. "Even in this era of widespread digital communication, we found that where people sit in relation to one another makes a huge difference."

One of the great challenges for the team was the way in which the system would randomly give Uruks different attributes. Players would sometimes be presented with an almost unassailable war chief, the product of a fortuitous roll of the dice who was, for example, immune to ranged and sneak attacks, cannot be branded and controlled, and who has inconsequential fears and insurmountable abilities. Such a character could block the player's progress.

"In the end we accepted and embraced that side-effect of the design," says de Plater. "We simply ensured that there were always choices. Initially, for example, we forced players to kill all five generals before they could progress. But there was no choice and that felt limiting and, depending on the targets' attributes, sometimes near impossible. So we made it that you only had to kill four generals, that way, if there's someone that's almost indestructible, you are always able to progress." Finally, in the face of a vast amount of data from the game's legion of QA testers (many of whom also worked on Arkham Asylum) Monolith tweaked the game so that the Uruk generals' trait attributes are never entirely random. Certain combinations were excluded, and every character has at least one of a set range of weaknesses.

While Shadow of Mordor's storytelling is arguably at its best when it's player-led, the team at Monolith still needed to create a linear, overarching plot line to run concurrent to the emergent narrative, to bring the story to a pre-written conclusion. "This, again, was a huge challenge," says de Plater. "We were totally learning as we went along." Late into the project Monolith hired Christian Cantamessa, the ex-Rockstar Games scriptwriter who worked on Red Dead Redemption and whose company now offers an expensive script-doctoring service for troubled games. "It was a very deliberate decision," says de Plater. "We wanted Talion's story to be, in some ways, modular and separate from the procedural storyline." The studio then hired Dan Abnett, the comic book author who wrote the reboot of Guardians of the Galaxy (which provided the basis for James Gunn's film), to come up with ideas for Uruk officers. "He devised a clutch of strong villain archetypes," says de Plater. "His ideas are so memorable: the guy who talks to the severed head resting on his shoulder, or the guy who has an unhealthy relationship with his axe."

Part of the way in which Monolith makes Mordor feel larger than it is is through what de Plater calls 'exceptions'. "You can see this technique in a game like 80 Days," he explains. "There you have complete choice about the route that you take on your travels, but Inkle also wrote in Easter egg scenarios, whereby a certain character will sometimes go off on a separate sojourn for a little while. When you add an exception like that it makes the world feel larger and more alive. That's how we approached Mordor. You add a layer over the main system comprised of exceptions. For example, we establish that, whenever you're beaten in battle the Uruk victor stands over Talion and taunts him. So we made an exception to the rule: the one guy who is completely silent. Things that break the pattern become memorable."

Despite the agonising development process, during which de Plater says many major and "painful" cuts were made to bring the game's scope into line with reality, Shadow of Mordor was a considerable commercial and critical success, reportedly selling close to a million copies in its first week of release. Copycats will likely follow. De Plater is the first to admit that the nemesis system can be transferred to almost any social hierarchy. "You could see it working with the mafia, the military, prison gangs," he says. "Anywhere there is a pyramid of power."

But as well as the ease with which the system mimics certain aspects of human relationships, de Plater believes this kind of storytelling is peculiarly of its time. "This is the era in which players share their stories on YouTube or Twitch," he says. "So you want to give players the tools to create their own stories. A game that has a purely linear story is immediately less interesting for both the video-maker and their audience. As a culture we're increasingly coming to value experiences in games that are unique to the individual. The nemesis system makes it possible to create user-generated content within the game's formal systems. That, I think, will be its lasting legacy."