Uncovering the heart of Undertale

Yep. You got me.

While it didn't quite come out of nowhere, nobody could have predicted just how huge Undertale would become this year. At the time of writing, 19,394 positive reviews to 321. Half a million sales, by SteamSpy estimation. Beating Ocarina of Time in GameFAQs' Best Games Ever list. Making people give a crap about GameFAQs' Best Games Ever list. It's quite the thing.

Few games have ever touched so many people so deeply, or been so misunderstood by their critics. I'm certainly not saying that I think Undertale is the greatest game ever, since I think we all know that prize goes to 1984 classic "Bouncing Babies". It's not, however, just a collection of in-jokes and drippy warm goo glued onto the back of Earthbound nostalgia, as you'd think from insult names like 'memetale'. It's something harder to process - an incredibly smart, well-written and insightful RPG that's comfortable enough to do the gaming equivalent of showing up in a tracksuit and sneakers. You look at any part of it and yes, it's simple. Combine the pieces, and it's special, and far more than just another parody of the JRPG style like Barkley: Shut Up And Jam Gaiden, Cthulhu Saves The World or those pretty tedious Penny Arcade Adventures.

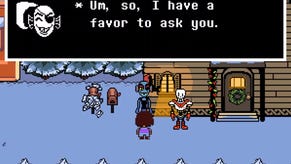

Even if you don't care about all of that blather, it doesn't hurt that it's one of the funniest games ever made. I've watched a ton of LPs since it came out, purely to enjoy the sound of people laughing themselves into a stupor at some of the jokes, both direct, like skeleton guards Sans and Papyrus' antics near the start, and indirect, like the raw raised-finger the game delivers to players who've murdered their way through the game only to end up having... a bad time.

It's wonderful humour, both because of the writing, and its incredible warmth. Just take a character like Papyrus, desperate to join the Royal Guard and make friends. (How bad? He's thrilled to get to go on a date, because he's heard that's how you get into the 'friend zone'.) He wields his self-confidence like a shield, but never to the point where his arrogance makes him unlikeable. He's just so adorably pathetic that you almost want to cut him a break and just let him catch you... and actually can, since Undertale's subtitle may have well have been "Toby Fox Knew You Would Try That", whether it's doing an act of pointless cruelty like eating a piece of a snowman in front of him instead of out of eye-shot, or killing someone to see what happens, then reloading, only to walk straight into a character knowingly going "You sneaky bastard..."

One of the biggest mistakes people make is assuming that the non-violence path, which isn't actually possible first time through, is the big gimmick. The Message, if you will. Certainly, Undertale values pacifism. That's the way to its real ending where everything works out. There's subtlety to even that though, including an open acknowledgement that you have every right to defend yourself from attack, with direct criticism coming more from committing specific horrible acts like lulling someone into lowering their guard and striking, or killing specific characters, and on a wider level, that since you have the power to save/reload, your decision to kill is always at least in part the decision to not try again and see if there might have been another route.

The larger picture is one of a deeper understanding. Your first playthrough, the longest, is about five hours of essentially being hunted. A hostile world, uncertain adversaries, survival. Chances are you'll do what you gotta do - repay aggression with aggression, show mercy to those who deserve it, have some regrets, like killing Toriel, the loving goat lady who just wants you to be safe and happy. This playthrough is about being the hero. It's all ultimately about you.

The second playthrough, even though most of the game doesn't change, goes differently. Now it's entirely the story of the monsters and their culture you meet. What you know about mechanics, about where it's all going, how the characters relate to each other. It's about peeling back the layers, either by going for the Pacifist Run, or simply experimenting to see what happens if, say, you kill an important character or go against how things went before. The fact that the game remembers past playthroughs and throws them in your face is really important. It's also only at this point that you can start picking away at the much larger story outside your personal quest, like the True Lab and the Amalgamates, Frisk, Chara and W.D. Gaster.

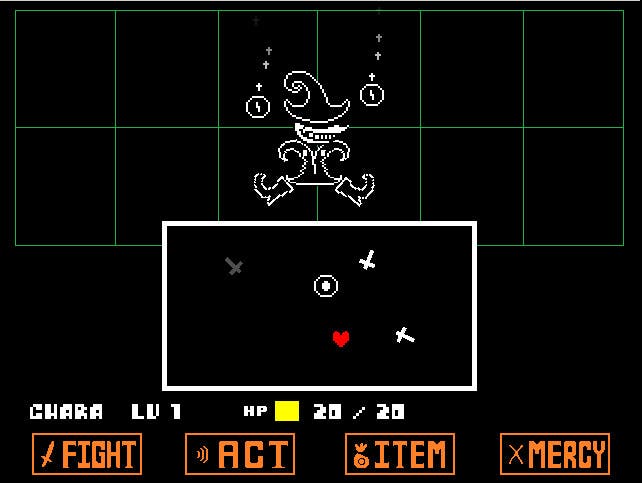

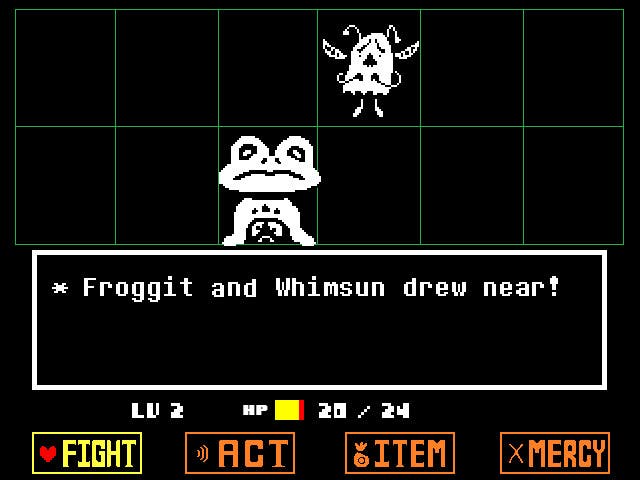

Taking a second pass also reveals many of the subtleties casually drip-fed in the background, like how many ways there are to deal with situations, how many opportunities for cruelty you might have walked past, or just how brilliantly elements like the combat system work. Take the first boss fight, Toriel, who begins a pattern of enemies using attacks to illustrate their mental state and will rather than the random assaults they seem to be. In her case, her opening salvos will wreck the average player, but because she's not actually trying to kill you, her final strikes are all pulled punches that will never hit. The same applies later to characters getting cross or uncertain, to two monsters combining their attacks, or to guard captain Undyne's growing fury. I won't call the battles outright character studies, but they're not just random mechanics.

Spending this extra time with the characters also reveals just how layered they are, at least by RPG standards. No, they're not exactly Walter White in terms of complexity, but there's a lot more to them than meets the eye. Sans the skeleton guard for instance, whose only interest seems to be torturing his brother with puns and pranks, ends up being a surprisingly complex figure whose attitude comes from a much darker philosophical place than expected despite never outright dropping it. Flowey wasn't always the friendly ally that you meet at the start of the game, without whom you'd never have learned how to collect vital friendliness pellets. Most of the main characters are living with at least one unfortunate past decision or regret.

And I think this is a crucial part of Undertale's success too. Most RPGs are built on forward momentum. You start here, usually outside The Town Where The Game Starts, you go there, to Where The Final Boss Is, and pretty much that's it. Bish-bash-bosh, game over. Undertale is one of the few that encourages you to dig deeper and spend the time with the characters that lets them be more than just a step on the road to your final destination. The responsiveness of the world is what makes it feel real, be it an item held over in the world from a previous game, or something as small as phoning someone who's on the screen and seeing them take the call. Spending more time with familiar faces makes them feel real, just as returning to Britannia in the Ultima games always felt like a homecoming of sorts. Old faces, old friends, new adventure.

You don't typically see this from a single playthrough, because in that playthrough you're likely in RPG Mode - the ruins, the town, the waterfall, the lava world, the final boss, credits. During that one, yeah, it's a bit simplistic at times, and the opening section in the ruins especially is a little bit dull. You're not really playing Undertale then though, so much as being introduced to it.

And really, nothing stands as a better testament to how effective the world and writing is though than the fact that not only do most players struggle to do a Genocide Run. Undertale is confident enough to openly mock the fact - a direct shout-out to people who couldn't bear to murder Papyrus and Undyne and the rest, but instead choose to watch what happens on YouTube. (A fairly common response in the comments being variants of "Yep. You got me...")

This playthrough strips out almost all of the comedy entirely, recasting the whole game as little more than a serial killer silently stalking their way through the world. Buildings are locked. Monsters have escaped to safer ground. Even inventory items change names and descriptions to remove the levity of items like 'ButtsPie' or the slow-boiling Instant Ramen joke. Here, you're simply a destructive force of pure murder and malice... and it's hard not because it's very challenging (except for one notable fight) but because only a monster would murder characters like Papyrus, still desperately trying to awaken the good in you even as you obliterate him, or worse, give the characters their happy ending... only to hit reset and steal it away from them. And why? Because of boredom, or to see what would happen. Who's the real monster, eh?

This is not the kind of thing that deserves to be brushed aside with a quick 'killing people is bad, mm'kay?'. There's real thought and love - not LOVE - behind it all, and a subtlety of writing and deep design that's all the more impressive for being tucked away behind slapstick comedy and over the top JRPG hooting. Sure, there's cheap gags like characters believing anime is real and direct references to Earthbound and other JRPGs (such as a parody of the Final Fantasy VI opera scene), but they're in the minority. Most of Undertale stands alone as its own creation, and one which rewards both ripping through it for the yuks and taking time to appreciate it.

It's one of the best games of the year. It's one of the warmest games of the year. It's easily the best surprise of the year, and one that's exploded into a whole mass of fan-art and fan-games and songs and other cool stuff that shows how many people love it right back. Just be careful if you search for it on Tumblr. Even with a dedicated alternate tag for Rule 34 stuff to keep the main tag clean, there's definitely some stuff you... ah... maybe don't need to see.