Why did ancient Egypt spend 3000 years playing a game nobody else liked?

From the archive: Afterlife is strange.

Editor's note: The Egypt-set Assassin's Creed Origins is out this week, and in a bold bit of opportunism we thought we'd republish Christian Donlan's wonderful piece on Senet, the board game played by ancient Egyptians. The piece was first published last year.

The clay pot theory of history

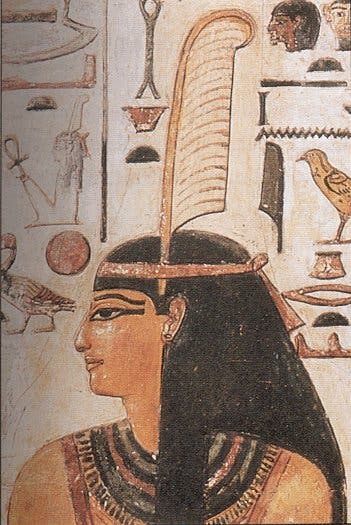

It was hard work being dead in ancient Egypt. You had to put the hours in. Upon death, ancient Egyptians believed that your ba - soul is the closest word we have - was kicked loose from your body and freed to roam the lands. This freedom came with limitations, however. Every day your ba left the tomb where your mummy rested and wandered in the heavens. Every night, it had to work its way back home, descending with the sun god to the world of the dead and undergoing great trials, before it finally rejoined the body in an act of supreme spiritual renewal. As above, so below: the Egyptians believed that the sun was born every morning and died every evening. The ba mimicked its journey through the sky.

In truth, being dead was pretty hard going even before you got to all of that. Take Nesperennub, Beloved of the God, Opener of the Doors of Heaven. Nesperennub was a priest and advisor to a pharaoh - possibly Osorkon 2 - and when he died in Thebes somewhere around 800 BC, the people tasked with embalming him stuck a small clay pot to the back of his head. We know this because the pot is still there, and it shows up very clearly in CT scans that Nesperennub's mummy was subjected to in the early 2000s as part of a "virtual unwrapping" conducted by the British Museum, where the priest, and his ba, now count out their days.

For a while after the pot was rediscovered, however, I vaguely remember reading that nobody knew exactly what it meant. The assumption, I think, was that it could be important, because Nesperennub was important. He was Opener of the Doors of Heaven. The appearance of the pot was therefore quietly troubling, I guess. No other mummy had even turned up with a pot on their head, and there was no mention of anything like it in the literature. Also, it was barely a pot if we're all being honest: a rough-hewn object made of unfired clay, still bearing the fingerprints of its ancient manufacturer.

Since this was Egypt, however, the smart money was on some hidden aspect of the ancients' famously elaborate death rituals. In one article I read at the time, a symbolic placenta was mooted. But why? A soul catcher? Unlikely. The ancient Egyptians located the home of a person's consciousness in the heart - a bad guess that has left lingering traces in many cultures to this day. They dismissed the brain entirely, calling it "the marrow of the skull" (and they weren't alone in their confusion by any means; Aristotle thought it was a radiator). Egyptian embalmers scooped the brain out and binned it. No special treatment needed. Besides, the ba was supposed to travel. Why trap it beneath a pot?

The truth is both more illuminating and more human than you might suspect. Let's imagine the scene. An embalming tent in Thebes, tasked with a high-prestige job: to prepare a renowned priest for the afterlife. The mummification process would take 70 days, and was performed by experts, most of whom were priests themselves. After the internal organs were removed and the body was dried with natron (a kind of salt), aromatic resin would be applied to preserve the deceased for the aeons that lay ahead. This resin was expensive, and in Nesperennub's case, the embalmers appear to have applied a little too much. It started to run down the back of the dead priest's skull. And so, in order to salvage as much of the pricey stuff as possible, one of the embalmers grabbed a lump of clay and made a crude receptacle to place under Nesperennub's head to catch it.

Then they forgot about it, for a while at least, and when the time had come to wrap Nesperennub's skull, disaster: the resin had stuck the pot to his scalp. The embalmers made a few attempts to remove it, tearing the priest's dried-up skin in the process, and then? Then they made the best of a bad job, sending Nesperennub into history, wrapped up and in his sarcophagus and with a clay pot on his head. Who would ever know?

I love the clay pot story because it acts as a tunnel that leads directly to the distant past. Wander in and it shows you that we are not so different after all. The ancient Egyptians can so easily become the unknowable titans of the desert, chilly religious fanatics who thought about death a great deal and built hulking tombs of fearful symmetry. We visit their looted palaces and might assume that they too were as hollow and as echoing as these places seem to us today.

But with Nesperennub and his humble pot, here they are all of a sudden, up close and recognisable, human-sized, hands sticky, minds flustered, frantically trying to stop a simple klutzish mistake from getting out of hand. This fleeting domestic insight into the lives of people who lived millennia ago seems so much more revealing than the high culture stuff - the pyramids, the spells, the gods. Ever since I first heard about Nesperennub and his endearingly ridiculous secret, I've been trying to find other similarly human glimpses into Egypt's warm-blooded past. I've been looking to expand the clay pot theory of history.

And it made me think: maybe games might provide a similar way in. Games! Suddenly, we get to see beneath the broad sweep of rulers and wars and into the lives of ordinary Egyptians. With games, we're right there in people's houses, playing with the draughtsmen, arguing over our fortunes and throwing little sticks to make a move (the Egyptians invented breath mints and paper and triage, but they didn't invent dice). So it goes: some people play well and still lose every game. Some people rise to power only to end up with pots stuck to their heads.

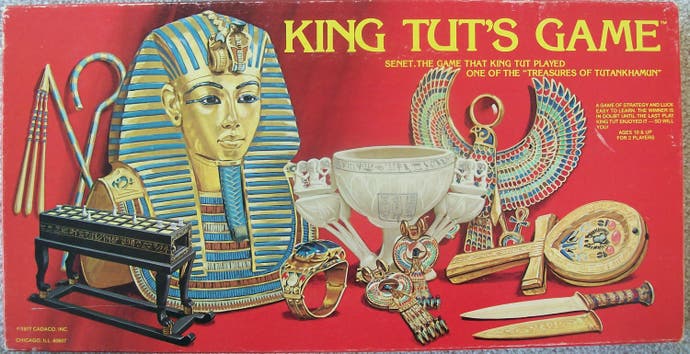

If I was looking for games, I knew my ultimate target: Senet, the favoured game of the ancient Egyptians, played on a board made from three neat rows of 10 spaces each. Senet was played in Egypt for over 3000 years, and was responsible for one of the first recorded instances of trash-talking, captured on the wall in the tomb of Pepi-Ankh at Meir and itself dated to around 2300 BC. Player One: It has alighted. Be happy my heart, for I shall cause you to see it taken away. Player Two: You speak as one weak of tongue, for passing is mine.

Senet is one of the precursors of Backgammon, amongst other things. Backgammon! I have personally played this just once, on the night train from Cairo to Luxor in the late 1990s, tempted south not so much by Karnak Temple and Thebes, where Nesperennub met his sticky post-fate, but by a poetic line describing a cheap hotel in my swiftly-fragmenting travel guide: Mr Magdi will let you sleep on the roof for the price of breakfast. That sounded like the life! Footloose, but also kind of timeless. In Luxor I could be a rooftop-hopping nomad. Over the years, a little of Mr Magdi's knockabout romance stuck to Backgammon and inevitably mixed in with Senet too. And the romance held firm until the night, a year or so ago, that I loaded up a digital version of the ancient game on Steam and started to play.

I tried to play anyway, but there was a crucial problem. Senet didn't seem to work particularly well as a game. Where was the drama? Where was the tactical thrill? What was I missing? Or, possibly, what were the ancients thinking when they chose this game as the one, above all others, to stick with for three millennia?

Senet was the favoured game of the ancient Egyptians. I had read this in books for years, and, in my ignorance, it always made sense. it made sense right up to the moment I actually tried it myself - after which it seemed to hint at a great mystery.

"I can't even remember what made me do this."

Senet, or the passing game. The name is sonorous and melancholic, but it refers, rather prosaically, to the draughtsmen, which are able to pass each other as they move across the board. Senet is old. It's older than writing - in Egypt at least. We know this because a side view of the Senet board was actually used for the hieroglyphic sign, Mn.

The Egyptians, never the most spontaneous of ancient peoples, had a lot of time to get Senet right. The oldest surviving boards, unearthed in a First Dynasty tomb at Abu Rawash, date from around 3000 BC and the reign of King Dewen. Some people suggest it reaches as far back as 3500 BC. And forward? The last Egyptian board found was sketched on the roof of the hypostyle hall of the temple of Hathor at Dendera, and dates from the first century AD. By this point, Egypt was a province of Rome, so ancient Egypt's favourite board game pretty much outlasted ancient Egypt.

Some of what we know about Senet comes from the tomb of a man named Hesyre, who lived around 2660 BC. One of Hesyre's many titles was 'chief dentist', according to the literature, which sounds like a pretty exhausting gig in an empire of over two million people. He was also a major game collector. His waiting room must have been a laugh riot. His tomb certainly isn't bad, although a nasty case of plundering has left it with little that wasn't slapped onto the walls. Still, in his resting place at North Saqqara, we see paintings of a complete Senet set, alongside paintings of complete sets for other popular games like Mehen, which was played on a board shaped like a coiled snake.

Paintings of complete sets are important, because when it comes to physical objects, almost nothing from the ancient past makes it to us completely intact. Bones crumble. Jewelry breaks. Chessmen are swallowed by the earth. (Some were carved out of bamboo and could actually be eaten: to the victor, the spoils.) As a result, Senet's precise rules are lost - but there have been plenty of people who have been willing to make guesses.

Two of the most educated guesses come from the 20th century, and it's here I initially turned in my quest to understand why the ancient Egyptians loved a game that didn't seem to be particularly lovable. The first educated guess is by R.C. Bell, a British plastic surgeon who died in 2002, and who devoted his life to collecting and cataloguing board games from around the world. His two-volume work, Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations, is a wonder: lively, bright-eyed and practical, and filled with detailed rules and diagrams. It's a perfect rainy afternoon book.

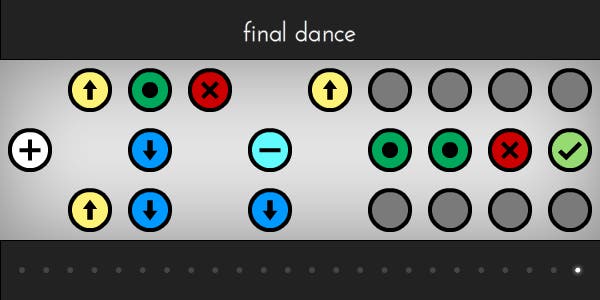

Bell calls Senet Senat, or The Game of Thirty Squares, and he refers to the throwsticks, which stood in for dice, as gambling sticks. He felt certain that Senet was a two-player "table" game along the lines of Backgammon, and the rules he suggests are entirely sensible. Each player places their collection of draughtsmen alternately on the first squares of the board, and the aim of the game is to make it from the start to the finish, and from there to then get all surviving pieces off the board. The board itself is treated like an s-shaped snake, so you advance left to right along the first 10 squares, and then loop around and take the next 10 squares right to left before looping back once more. Players take turns, and when somebody lands on an enemy piece, they can capture it and remove it from play. The last five squares of the board leave you safe from capture, but require exact throws to move forward from. The player guiding most pieces off the board wins.

The first volume of Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations was published in 1960. Almost two decades after that, in the late 1970s, someone else had a go at cracking Senet. This time it was Dr Timothy Kendall, a young Egyptologist from the US. Today, Dr Kendall is rather hard to get to talk to, as he spends a large chunk of the year working at Jebel Barkal, a mountain surrounded by ruined temples and palaces in the Sudan, and a location that once marked the southern limit of the Egyptian empire.

He is worth the effort: rigorous but sprightly, an ideal academic and thrilling company. When I contacted him out of the blue on a Thursday afternoon to propose an interview, within five minutes of picking up the phone he was quoting verses from the Egyptian Book of the Dead to me in a quavering voice. Days later, he sent me a photocopy of his booklet, Senet: The Rules of Play, which was published in 1978. In the top left corner he had written: "Hypothetical, but based on best evidence!" This was surely the man who could bring Senet back to life for me. He had done it once already.

Dr Kendall's rules are not dramatically different to Bell's, but there are a few interesting alterations. Dr Kendall refers to the 30 squares as houses, and introduces a neat spatial element that makes the game a little more tactical. A single draughtsman on his own - that is, one placed in a house between two empty houses - is classed as undefended, and may be captured by another player. If two matching draughtsmen are placed together, however, they are defended, and are effectively blocking other players from landing on them.

More importantly for the pacing of play, captured pieces are not removed from the board, but are knocked backwards, making for a game that has a little less bloodshed and a bit more pushing and shoving to it.

Dr Kendall also has a lot to say about the final houses on the board. House 27 is the House of Waters, since it was often decorated with wavy lines in Senet boards from the New Kingdom (from the 16th century BC to the 11th century BC) onwards. A piece that lands in the water must return to house 15, which is known as the House of Repeating Life. Dr Kendall also suggests that players may continue a turn until they have thrown a two or a three, and they should complete their throws before any moves are made, opening up greater tactics, since, should you throw a four and a three, say, you could either move one piece by four houses and another by three, or move a single piece by seven houses.

When Dr Kendall isn't in the Sudan, he lives in Salem, Massachusetts, and it's here that I finally catch up with him for a proper discussion on Skype one morning. His laptop camera reveals a cheerful man with busy white hair, fine-rimmed glasses, and a deceptively delicate air to him. His voice is quiet and aristocratic and he seems slightly sunburned from a recent trip abroad. A gentleman adventurer, he is the sort of man you might put behind the wheel of a Saab.

Also: he is very surprised to be having a conversation about Senet. "It was a long time ago!" he laughs, throwing his hands up. "That was back in the late 1970s!"

Senet, in other words, has not been his life's work. "I can't even remember what made me do it," he says, after a long pause. "I guess it was the discovery that there were texts that described people playing the game, and that there was this game board that had every single square inscribed, and so you could follow the text with the game board and maybe decipher how it was played. But I mean, gosh, that's a long time ago."

Even so, I am struck by the thrill of this. Archaeology isn't just about working away in the sand with a toothbrush, trying not to break something precious as you pull it out of the earth. It can be a creative, theoretical enterprise, a means of reconstructing the thought processes as well as the material culture of ancient people - a way of getting inside their minds as well as their tombs.

"Basically, we have a certain amount of information from these texts about Senet," Dr Kendall explains. "We know which direction the pieces moved in. We know what their objective was, they had to get on this beautiful house, and then they had to cross the water square, and then they had to get off the board. You have a certain amount of information that is absolutely proven. The question is: you know they weren't jumping back and forth from one line to another, so it had to be a kind of competition for position on the track, the S-shaped track."

So what next? Dr Kendall is unambiguous. "So then you have to invent a way in which the opposing pieces compete on this track. That's the only invented thing. Because we actually know how the throwsticks were used to move the game along."

I ask Dr Kendall if he can remember the first game of Senet he played after reconstructing the rules. A good-natured groan. "The guy that I manufactured this with, we played it and played it," he said. "And then after a while we discovered some glitches in the original rules and then we made variations to compensate." He laughs. "I guess that's the way most design happens. I guess it's like designing a computer or something. You have to get all the bugs out of it. It's the same with games."

I pause here because I know that, after I close down Skype, I'm going to load up that Steam version of Senet again - a version that is based on an amended set of Dr Kendall's own rules - and I'm going to have a second, proper go on it. And to do that I need to know a bit more. I need to know what Dr Kendall honestly makes of Senet as he has it. Senet that is "hypothetical, but based on best evidence".

"Well, you know, it seems like the fun, it can't just be pure luck," he ventures. "You have to have a little bit of strategy. It seems as if there was a little bit of skill involved, that would help to make it more fun. But it's hard to figure out how you can put the skill in when everything is just based on the numbers that come up on the throwsticks." He frowns. "In that case maybe the fun might be the gambling. Whether you win or lose something. I don't know. I don't have any good ideas about that. I haven't put my mind to this in a very long time, but it seems like all of these games are pretty much throw-the-dice-and-move-the-pieces. Unless there was an intellectual component, where you have to recite certain texts or something."

He nods. "They probably gambled on it. Gambling's probably, you know, what made it a little more exciting."

Dr Kendall left me with the sense that I wasn't playing Senet correctly. Our chat reminded me, in a roundabout way, of my first night in Cairo back in the late '90s, on which I stood nervously at the curb of a busy downtown junction for about 10 minutes waiting for a break in the clamouring procession of lorries and cabs. I was tiny and alone beneath a full-building advert depicting an avocado bathroom sink, four storeys tall and drawn in a disconcertingly heroic high style. I would probably still be on that curb right now if it hadn't been for a long-limbed, rather beautiful Egyptian man in gigantic specs and a flapping Hawaiian shirt who lead me out into the traffic with a dangerous confidence, saying, "Boy, come on. You have to learn to walk like an Egyptian." He really said that. (I never did learn.)

For Senet, weird and naff as this sounds, maybe I had to walk like an Egyptian. My theory up to this point was that, hey, people are people wherever - and whenever - you go. Maybe Senet was actually arguing otherwise. I loaded up Steam and tried to understand this strange back-and-forth game. I tried to look at it differently. Boy, come on.

And, well: partial victory. Senet's not a dull game, but it is fiddly. As it's about getting your draughtsmen off the board, there's a sense of bureaucratic pushing and shoving to it - a bit of a packed elevator experience. With all the squares that require specific throws, and all the squares that are blocked and defended, the RNG is rather strong. And, since in many cases you don't really have a choice of which piece to move, as the end-game approaches, it gets progressively less tactical. After an hour or two I had yet to play a game in which the likely outcome didn't veer back and forth madly in the final two minutes. This could be exciting, but since most of the action is actually relegated to the last 5 of the 30 squares - no! houses! - there's a fair amount of waiting to get to that point. Senet feels, more than anything, like a game that is won or lost by stragglers. It's certainly not a game with a massive scope for heroism. Leave the heroism to the gods and the giant bathroom sinks. You can see why people may have felt inclined to bet on this.

And yet I felt something else, too. Talking to Dr Kendall had reminded me that I was engaged in an activity very similar to something that Nesperennub may have known. If I had met him, through some as yet undiscovered technology, we might be able to commune over this. I could almost imagine reading his body language and facial cues: the smile of delight when he knocked one of my pieces into the water, the comradely shrug when I rolled my fourth consecutive three and had to retire, again, without a useful move. Nesperennub, long, aristocratic head leaned low over the board. Nesperennub, squeezing his lips together as he ponders his options. Senet, eh? The passing game. The great leveller.

One bottle of lemonade

Maybe - and this seems almost blasphemous - games really have changed. Maybe people have changed, and today we want different things from games than the ancient Egyptians wanted from Senet. Maybe they found the shuffling rhythms of the game of passing to be thrilling, or at least true: the smallness of human life captured against the unchanging vastness of the landscape of the gods. Is that it? Senet is a game in which the player can often feel irrelevant, halting and endlessly undecided when contrasted so sharply with the beautiful order of the three lanes, the 30 houses. And the only objective? The only hope? To get off the board. Not quite an escape. No. More an understanding that we were never meant to be there in the first place.

I was guessing, frankly, so to get a better insight into the world to which Senet belonged, I went to the British Museum to visit a friend and colleague of Dr Kendall.

Dr Irving Finkel is a reader and translator of Cuneiform (the first written language on Earth and also a word that I discover, three minutes into our conversation, that I have been seriously mispronouncing for 20 years), a leading authority on the pre-Biblical flood narrative, and also an expert on board games - ancient and, I suspect, otherwise.

And he is strangely perfect, vast hair and vast beard, tweed and corduroy, padding across the great bright hall of the British Museum to meet me. He has that slight impatience of a person who lives inside his head a lot and is always having interesting conversations in there, and he has the absolute best route to the office of anyone I have ever met. Off to the left, past the Rosetta Stone, sharp turn after Ramses II or whoever it is, and briskly upstairs, towards the inevitable unmarked door that you would never normally notice. And then, battered key already disappearing back into pocket, through to - what's this?

I'm tempted to call it the real British Museum. The working building. Backstage, where the floor is suddenly scuffed concrete rather than marble and glossy parquet, where great things are stacked all around, where parchments are rolled and stuffed - carefully - in little wooden cubby holes, and where Dr Finkel himself has a narrow workspace, crippled bookcases overflowing on either side of a large window offering an unspoiled view of an entirely featureless wall. There's an old computer on the desk and the entire room is held in the gentle gaze of a man in a faded sepia photograph that's been propped upon nearby clutter. Theophilus Goldridge Pinches (M.R.A.S.), a pioneering Assyriologist, the man who offered the correct reading of the word "Gilgamesh" when the rest of the world thought it was "Izdubar", and "the finest scholar the museum ever had," according to Dr Finkel. Dr Finkel should probably know. His job title is the Assistant Keeper of Ancient Mesopotamian Script, Languages and Cultures in the museum's Department of the Middle East. In a multiple choice scenario you would not struggle to match his headshot with his occupation. Unless one of the other options was "wizard".

Dr Finkel is not an establishment type. He is scandalously entertaining to listen to, whether he's referring to the ancient Egyptians' "fatuous way of painting everybody looking like cardboard," or unleashing one of his elegant multi-part sentences that seem to prop up the traditional viewpoint of a subject before undermining it, fatally, with a jolting sub-clause that goes off like a landmine. He met W. C. Bell, he of the suggested rules for "Senat", as a young boy, when he got Bell's book out of the library and then sent him a letter to tell him how much he enjoyed it. Bell invited him up to Newcastle - "it was the days before we were all worried about child molesting," - and talked to the young Irving Finkel about his collection of board games.

"It was a wonderful thing!" beams Dr Finkel. "It completely affected my entire life. Because he had a whole houseful of stuff and he was the sort of bloke who didn't have a lot of money, so he found things in junk shops and didn't know what they were. And he made replicas of things that he couldn't find. He worked things out. Academically it's got holes in it, but it really got me involved." He pauses. "He was very kind to me."

I try out my theory on Dr Finkel: that games offer what is potentially one of the more human perspectives on the ancient past. That they provide a way of looking at ancient people in a way that makes them more recognisable.

"I think that's right," he says. "And I think Senet's probably the weakest illustration of that argument."

Dr Finkel, it transpires, is not a fan of Senet. "The first crucial point to make," he tells me, leaning back in the creakiest chair I have ever encountered, "is that board games exist long before ancient Egyptian culture was up and running. This goes right back into the Neolithic."

The Neolithic, or New Stone Age! A period that's generally seen as lasting between 10,200 BC and somewhere around 2000 BC. That takes you from the invention of farming to the widespread use of metal tools: a busy time. In the Middle East, in places like Jordan, Syria, Israel, the Lebanon, there are Neolithic gaming boards that take the form of a parallel row of holes, usually five. These are crude boards made of limestone, and you find them all over the place. "So this comes from a horizon when homo sapiens is living in some kind of urban complex," Dr Finkel explains. "Usually walled, lot of people living together, shared responsibility, somebody in charge, all those sorts of things, even though it's before pottery. It's the beginning of the domestication of plants and animals, but it's before pottery. We have in this horizon a good distribution of these objects which unquestioningly are gaming boards as opposed to counting devices or calendrical things."

Scattered over the Neolithic world, all of these boards are, essentially, different versions of the same game. They're spontaneous eruptions of a single brilliant idea: player one against player two in a race. And this, to Dr Finkel, is the first hint of why games might be important.

"It's very interesting to wonder whether they might not be more deep-seated in human development," he says, tentatively and then hitting his stride. "Because my own view is that games probably had something to do with the whole scenario of the evolution of speech and grammar and 'I'm me and you're you and I can run faster than you.' That sort of idea. That games might come into existence as a symbolic and harmless form of violent opposition.

"I think it's to do with the very time when, however it worked, speech and grammar became part of it all. I have a theory that opposition is the crucial thing: 'I'm me and you're you' is like the first grammatical distinction. Once you've got that agreed, once somebody realises that one noise means me and another means you, everything else follows. You have to have plurals, you have to have names, you have to have verbs and I think it must have been a very volcanic matter that counting, which is an abstraction, and speech, which is an abstraction, and possibly music, singing and sounds, all of those things probably came in one fizzy bottle of lemonade and I think that probably this stuff, the board games, came out of it too." Deep breath. "It was probably a huge jump. It wasn't: 'Oh, I've got an idea, why don't we have one square and...' I think it must have been more that once something happens with the human brain it goes in a very, very fizzy way."

And does Senet, which turns up after the Neolithic, have that same sense of fizziness? Dr Finkel suddenly sags back in his chair. He glances at Pinches. The very thought of Senet seems draining. "I think I've tried all these things," he says, "and Senet as represented in this shuffling thing is a laborious and unexciting matter." Dr Finkel thinks for a few seconds. "The most lucid writing about how Senet might have worked is certainly Kendall. He's a very gifted scholar and he writes with a great deal of common sense. His booklet about it is probably the best thing that's been done about it. And he records what we know and what we can say. And yet."

This and yet is the start of another mystery about Senet - perhaps the greatest mystery of all. Namely: The ancient Egyptians played this game throughout the entire lifespan of their empire, but nobody else did. Senet didn't travel. And that doesn't make any sense at all.

Because games travel. Dr Finkel's written about this at length, most succinctly in the introduction to the book Board Games in Perspective, which he edited several years back. "In fact games spread from culture to culture in a way that has hardly any parallel," he writes. "They exist on a level impervious to religion or politics, and represent a free means of communication between people that nothing can successfully interrupt."

You can hear it when you read that. You can hear the march of games! Games crossing battlefields, scaling the wires. Football on Christmas day in the trenches. (3-2 to the Saxons, allegedly.) Tetris busting out of Communist Russia. Leaders unable to do anything except give in and play along like everybody else.

But Senet? "The interesting thing about Senet," Dr Finkel tells me, "is that it's unlike all the other games of the Middle East in my mind because it's a very well represented or strong presence in Egypt, probably fluctuating in periods, but it's not played outside in the rest of the Middle Eastern world as far as we know. There are some very crude boards from Cyprus, which look like the kind of things workmen did when they're having their sandwiches, some of which have three by ten squares, some of which don't. Everybody says, 'This is Senet on the island of Cyprus.' I don't believe it myself. I think the general rule is that the games of the Middle East that we know about, which is the Game of Twenty Squares, The Game of Fifty-Eight Holes, were played everywhere. In Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Cyprus, Turkey, sometimes as far afield as India and Pakistan.

"And these games, such as we have, have some very important characteristics which explain why this is the case," he continues. "The first point is that there's an evolutionary process loose in the world that means when a game comes into existence or is first thought of, if it's no good it dies very quickly. When people have a game when they try inventing new ideas about it, they also die very quickly. And actually what you have, in the games that we do have, is they're all race games, except Senet, which is probably not quite a race game, so you have this distillation out of all the potential games that you might have into quite a small tightly knit group, and they go everywhere, and they spread without writing and certainly without military conquest all over the Middle Eastern world in increasingly wide circles. So they have a life that is under the radar in the sense of politics or anything like that. They just go from merchant to merchant. Mercenary to mercenary. And so they spread."

They really did. Senet's biggest contemporary rival is the Game of Twenty Squares, also known as the Royal Game of Ur, since a handful of boards were unearthed in the 1920s by Sir Leonard Woolley in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, a Sumerian city-state located in what is now southern Iraq. Dr Finkel's a useful person to talk to about this, because, as Bell and Kendall sought to uncover the rules to Senet, he worked out how the Royal Game of Ur was probably played.

"What actually happened was, when I got here to the British Museum, I found this tablet that nobody had read properly," Dr Finkel tells me. The tablet was written, in Cuneiform, by a Babylonian astronomer. "I realised it was the rules for a game," laughs Dr Finkel. "And then realised it was The Game of Ur. It took a lot of work to solve all that. That brought my interest in games, which was just private thing, into a different perspective."

The Royal Game of Ur knew how to travel. It entered Egypt by the middle of the Bronze Age, which started around 3150 BC, but it has also worked its way through Pakistan, Persia, Iran, Syria, Turkey, Cyprus and Crete. A form of the game survives to this day in India, where it is called Asha. It's staggeringly successful at staying alive and on the move. And there's an obvious reason. "That tablet I translated," says Dr Finkel, "the point about it is the game that you can squeeze out of it has an elemental good quality about it. A comes from one side, B comes from the other, and they race up the middle and off the end. It's infinitely more dynamic than Senet. I always look at this from the point of view of what would happen if you played them at home. One of the points of playing a really good board game is to annoy your brother or sister by beating them. With the Royal Game of Ur, right up until the last minute there is this question of who's going to win. Whereas with Senet, you shift back and forth at the end a bit, but nobody would give a damn after half an hour anyway."

The Royal Game of Ur really is brilliant, and it's the board that makes it so. Like Senet, the task of each player is to get their pieces to safety, but with Ur, both sides have their own starting points, and then they have to meet in the middle row, where the territory thins out and they're suddenly stumbling over each other. There are safe spots, marked by rosettes on the spaces, but otherwise it's a bloodbath, the Sumerian equivalent of Baby Park in Mario Kart Double Dash. Land on an enemy piece and you send them back to the start.

Ur's so full of temptation, because each safe spot also grants you another turn. It's so tactical, too, because you're constantly choosing between getting one of your draughtsmen to safety or bringing another one into play. It feels fair, unlike Senet, because both sides start in identical circumstances, and as play moves to that alleyway in the centre, the whole thing becomes a game of wit, speed, skill and cruelty. Confrontation is unavoidable. The game's over in minutes. Would play again.

Speaking of temptation, it's tempting to see Ur as a game in which the player is in control of their own destiny, and Senet as one in which they are buffeted by a mercurial fate. It's also tempting, although almost certainly incorrect and probably unintentionally offensive, to wonder if a little contamination hasn't taken place. No, a little transference. Senet, as Dr Kendall has it, is a magnificently reasonable game, in that both sides are equally troubled by circumstance. It has Dr Kendall's obvious gentleness, his even-handedness, in its measured procession to the final goal. The Royal Game of Ur, however, is knockabout and aggressive. It's a game in which you throw your whole energy into causing mischief for your opponent, a game in which, once you have made your moves, you lean back in your creaking chair and call things as you see them.

The journey of the soul

Here, then, is the problem as I see it. For Senet to have been played for so long in ancient Egypt, it must have had something great about it. And yet! If it did have something great about it, shouldn't it have been played outside of Egypt too? How do you have one circumstance without the other?

The short version? Dr Finkel states the case with weary precision. "I think the fact is that this is an Egyptian game par excellence and one of the reasons that nobody else wanted to play it was that it wasn't very interesting."

The long version? The long version is much, much longer.

Perhaps, for starters, part of the reason Senet didn't travel was because of the way the Egyptians ran their empire. Could it be that the ancient Egyptians were isolationists rather than imperialists? "That's a good question," says Dr Kendall. "They didn't have very much success converting anybody to their way of thinking in the Levant. They conquered all those people, Canaan and all those cities. They ruled them. But with a few exceptions, like Sudan, which they saw as part of Egypt, they didn't convert them. They considered them Asiatics and people with their own gods and cultures. They didn't try to change them."

This was pragmatism, according to Dr Kendall, but it does also suggest that Egypt might not have been too concerned with exporting culture such as favoured games. On top of that, there's the possibility that we still haven't entirely cracked Senet yet - that there is simply more to it in the first place. "There's more than one view of it all, and I have a feeling that there's probably more to be said about Senet really than has been said," muses Dr Finkel. I mention to him that even Dr Kendall wasn't sure he had totally nailed it. "Oh, he didn't," says Dr Finkel. "He had ideas. It's very clear what he wrote and it's very sensible, but it's not nailed."

Murkier still, it's possible that the ancient Egyptians had an entirely different understanding of even the most basic elements of Senet. John Tait is the emeritus professor of Egyptology at UCL, and he's spent a lot of time trying to work out whether the ancient Egyptians gambled on the games they played. One of the most striking ideas suggested by his research is that the very notion of odds may not carry across particularly cleanly between the ancient world and the world we live in today. Modern games often use dice rolls as randomisers, allowing for an element of chance within the design, but there's no indication that the Egyptians who played Senet explored the concept of probability as a measure of likelihood - and yet they had throwsticks that seem to perform a similar job to dice.

It's possible, then, bearing Professor Tait's work in mind, that Senet's reliance on the randomising factor of the throwsticks may not have seemed much like a reliance on a randomising factor to the game's original players. Maybe Senet was a game in which the gods played alongside you, and the casting of the throwsticks became a form of divination: the gods exerting their will on the board. Would that have made it more engaging?

(It's worth mentioning here that when I emailed Professor Tait to discuss his work on this matter, he was eager to point out that it's very dangerous to think of the ancient Egyptians as being different in some crucial way. Modern people often display a highly personalised take on probability too. "The dice are really with me today.")

Divination can be surprisingly tricky to separate from ancient board games in general. Take the Royal Game of Ur, which is itself tangled up with everything from astrology and the zodiac to the notion of fortune-telling using sheep livers - which some people suspect provided the origin of the unusually shaped Ur game board. And even setting probability aside, there is no question that Senet became increasingly religious the more that the ancient Egyptians played it. According to Dr Peter Piccione, the associate professor of Ancient Near Eastern History at the University of Charleston, South Carolina, Senet boards of the Old and Middle Kingdoms tended to be decorated in secular ways - with numbers and directions and little else. By the New Kingdom - the period between the 16th and 11th centuries BC - however, religious imagery is the norm, and there is a clear sense that a game that was already venerable has taken on an entirely new dimension.

Dr Piccione paints a picture of religion coming to Senet in waves, and over a long period of time. "At least 4000 years ago, the Senet game came to be associated with notions about the migration of the ba and the Egyptian funerary cycle of life, death and spiritual renewal," he writes in a paper titled, 'The Egyptian game of Senet and the migration of the soul.' Perhaps it was not a huge leap. Boards, as Dr Piccione notes, had always been placed in tombs since the Old Kingdom, even if the trash-talking in the associated wall art suggests that the game started off as a secular affair. By the 6th Dynasty, however, Senet was being depicted as a means by which living players could commune with the dead directly. "The fact that the game became a conduit of such communication indicates that it had acquired its own inherent religious meaning," Piccione writes. And telephoning the afterlife was just the beginning.

By the start of the 12th dynasty, Senet was connected to the deceased's ability to travel freely on earth, tying the game to the passage of the spirit throughout the day. By the end of this dynasty, it was also bound up with the ba's return to the tomb after its nightly journey through the netherworld.

Over time, in fact, the netherworld became increasingly important to Senet. The Senet Ritual outlined in Chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead enables the ba of the player to achieve the "mobility", as Dr Piccione has it, that is required to travel between the lands of the living and the deceased. Once the game became linked with the journey the sun god took through the netherworld every night, the Senet board effectively became a map of that hazardous territory. Senet's transformation from game to spiritual tool was seemingly complete.

According to Dr Finkel, these religious elements did little to help Senet as a piece of game design. "That turgid business about the underworld and each square having a special meaning, and weighing the soul and swallowing the demons," he says, "the most important thing it shows about Senet is that it's a game of steady progression, where luck is not really so crucial. Because if they utilised the game of Senet in this underworld in a way where what happened to you was contingent upon it, you wouldn't want the chancey thing to be quite so dominating. So it may give you some sense that the game itself was rather sedate."

Finkel's also unconvinced that being tied up with religion actually did much to keep the game afloat. "I think you can't go wrong if you take timepass as the sort of overriding box in which board games should always be fitted," he argues. "And that other things are local, or temporary, or flare up and flare down, but timepass is the plodding thing that makes it all work. I think that's actually nice to think about. And so Senet is everything to do with funerary stuff, but people also played Senet in pubs, not thinking about their souls for sure, maybe with completely different rules. In my view, the general rule would be that board games are essentially for enjoyment and essentially to fill in time when there's nothing better to do. People who talk about these things forget, for example, that in antiquity there was no internet. Television. Telephone. Radio. Or anything to do after dark apart from have sexual intercourse and go to sleep."

Could the religious aspect of the game be a reason that other cultures seem to have rejected Senet, however? Back to Dr Kendall, who says: possibly. "Why wasn't it popular outside of Egypt? Maybe because it was too involved with the Egyptian way of perceiving the cosmic, and the afterlife," he laughs. "Maybe because it was something that was related to the Egyptian religion whereas the Game of Ur was more overwhelmingly secular and could cross boundaries fairly easily. The fact that you have it in India, Syria, Babylonia, and then it goes to Egypt, maybe it spans all those cultures because it's purely secular. Whereas Senet, maybe it just got a little too involved in the funerary rituals of the Egyptians and therefore wasn't of interest to anyone else."

"I think that's unlikely," says Dr Finkel when I put this to him. "Because games exist below the radar, as I said. In India, you have people in the court playing Parcheesi with lifesize figures and jeweled dice, but taxi drivers round the back will be playing the same thing on a board made of chalk with bits of dung. The part of Egyptian culture where such religious matters were discussed or experimented with or taken for granted was not a great mass of people. Not farmers and sailors. There is a picture for example of two blokes playing Senet on a river, where they're sitting. That to me seems to be a board game that's got nothing to do with the underworld whatsoever. So I think, as I see it, there's the real life of this game, and then there's the funerary matter, and by virtue of what survives, we have an overwhelming prejudice - or rather contamination - from that funerary aspect. The secular stuff, that's its real life in a way, and I think it's salutary to bear that in mind."

The Back of the Board

One thing certainly did change once the game became more religious, however. Its audience grew in diversity. Commoners were soon playing the game as well as nobles and kings; women were playing as well as men. Senet games are suddenly turning up as graffito, scrawled on masonry blocks and pavements. One, according to Dr Kendall, is even found drawn in ink on a schoolboy's writing table.

I'm fascinated by this because it gives a sense of the game in situ, of the world going on around the board itself. "There are pictures of people playing this game in their everyday lives," beams Dr Kendall. "Then of course pictures appear in tombs. And the afterlife was meant to be like the daily life, so it was a type of amusement. There's a grotto up above Derel-Bahari where the workmen who were building the temple must have gone for their lunch hour. You can see on the walls there are pornographic pictures of the Pharaoh, which I guess was Hatshepsut. But on the floor, there are Senet boards scratched in the ground."

What Dr Kendall is getting at here - and what Senet is ideally placed to explore - is the surprising absence of boundaries in the Egyptian world between the sacred and the secular. As Dr Piccione is at pains to point out, "the secular Senet game was played for recreational purposes, while the religious version was performed to communicate with the dead, to effect the passage of the ba, and to achieve spiritual renewal. [But] it may well be that all of these reasons could be the purpose for playing the game at any one time.... The Egyptians did not distinguish between religious ritual and recreational activity. It is Western intellectual thought which separates these notions, and demarcates the sacred from the profane."

"I think I look at it like this," says Dr Kendall at last. "That there was a game called Senet, that was fun enough. It wasn't any less fun than any of these other games that are all just dice-throwing games, but then the people injected the funerary business into it to make it more exciting. To make it more interesting to them. And I think that was an added element that may not have changed the rules but that enriched it all."

If there's a human insight lurking inside Senet, then, it might be tangled up with this. And it's Dr Kendall who finds a way of expressing it that I can understand. "When you see that people put these things in their tombs," he says, "when you see a range of things coming out of tombs and these are the personal effects of people who lived and that this is what they wanted with them in the next life, you see that this was a major form of entertainment. Even in the Old Kingdom tombs, you see the tomb owner who's shown at great big scale, playing Senet with people at a small scale."

He pauses. "I think that's what got me about Senet in the beginning, you know. How long this thing lasted. It's so typical of Egyptian culture that people's habits, formed in the fourth millennium BC, were changed so little by time. Lately I've been interested in measurement. I discovered that the Egyptian royal cubit, which is 52.3 centimetres, was used throughout the entire period, without any change, from the middle of the fourth millennium at least until Roman times. And that sculptors and architects used this measurement and its divisions to create everything. Everything was measured according to this way, all the way through, from beginning to end."

But didn't Heraclitus state that the only constant is change? Was Egyptian culture a grand attempt to do something impossible, to fix the world in place and stop it from moving? Is Senet's longevity hinting at a mummification of culture, in much the same way that the embalming priests would mummify the remains of the anointed dead, like Nesperennub?

"The Egyptians had a concept called Maat," answers Dr Kendall, "which is loosely translated as order or justice, or righteousness. It simply means: this is the way things should be done. You had to do things the way they should be done in order to win favour of the gods. And the kings are always shown giving the little Maat figures - she was a goddess - giving Maat to the gods, and then the gods are giving life to the king. So the whole thing was: we know how things should be done. We know how things should look. We know what's the proper religion. We know the proper artforms. These are the things that should be perpetuated. So this order was a crucial part of the religion.

"I suppose it's the way that certain religions insist that you can't eat pork or you can't do this, you have to do things this way. The Egyptians took this concept to the way that everything should look. So if you have a religion, of course over time things are changing, but everything is changing within the concept of Maat. That's why everything kind of looks the same when you go to the British Museum and go through the Egyptian galleries. Everything is the same from beginning to end - up to a point."

Up to a point.

But nothing lasts forever, and things can start to change on a fundamental level long before anybody really notices. Even Pharoahs.

And so. There are two ancient games: Senet and the Royal Game of Ur. Two races games at heart, played on similar boards and with similar rules. But one game is slow, and one is fast. One is local and embellished, over the centuries, by religious thinking, and one is an interloper, abstract and uncomplicated, arriving from the Middle East with the Hyksos kings and then spreading at an astonishing rate.

For a while, these two games coexisted, and by the 17th dynasty, they had grown rather close. We know this because the game boxes have survived to tell us: Egyptian game boxes in which the draughtsmen and throwing sticks were kept safe within a little chamber, while the board served as a lid.

But this proximity is perhaps deceptive.

"And so the Egyptians make their Senet boxes with one board on each side," explains Dr Finkel, as he eventually shows me out of his office, through the door, down the stairs, past Ramses II (or whoever it is), and into the great bright hall at the heart of the British Museum. "Senet and the Royal Game of Ur together."

He squints in the afternoon light. "The most interesting thing is that you can tell from the hieroglyphic inscription on the game boxes that the right way up is the Royal Game of Ur, and the Egyptian thing that everybody's been playing for hundreds of years is on the bottom. Because nobody wants to play it anymore. Not even in Egypt.

"At least that's how I see it."

Illustrations provided by Kirsty Saunders.