Mirror's Edge proved that the best magic is based on limitations

The closing of the doors.

The best thing about Mirror's Edge isn't the parkour, the sense of movement and momentum, or even the sharp, bleached-out world that you're moving through beneath a vast sky of Sega blue. It's the doors: the red doors, each one opened not with a polite survival-horror twist of a creaky handle, but with a squeeze of the right trigger and an almighty slam. Doors you aim for at full pelt, doors you pound through, punch through, the clatter of collision accompanying the blinding whiteness that greets you on the other side, before your eyes have time to adjust and before the game pulls you onwards.

And it's perverse, really, that Mirror's Edge does such lasting service to the humble act of opening a door when the game itself is all about closing them. In a specific sense, at least. Magicians like to talk about closing the doors: it's a part of the secret repertoire that builds successful illusions, every bit as crucial as fake shuffles, palms, and forces. Closing the doors is about shutting down an audience's errant curiosity, answering their questions before they've realised they want to ask them, and directing them away from the things that will ruin the trick. Closing doors is about creating a path for the audience, about leading the audience right past all the things that will make them gasp with delight, while making sure they have the best views of the action. Yes: Mirror's Edge knows a thing or two about closing doors.

All games are illusions to some extent. I've been amazed, over the years, by the sheer number of designers and developers I've encountered who have Thurston prints tacked on the cubicle walls, or who insist on keeping a pack of Bicycle Black Ghost playing cards in a jacket pocket. But Mirror's Edge makes the connection between magic and game design unmissable. Its first level is a case in point: a first-person race along rooftops and through office backways, where each time your eyes drift down you see your feet working away beneath you, and every grab at a ledge is framed by your grasping hands. You're really here, you're really doing this, the game seems to be whispering, and then at the end, a leap onto the skids of a chopper offers a glimpse of yourself in the mirrored windows of a superscraper. Inside and outside at once. Ta-da!

Mirror's Edge goes to such lengths to convince you of your presence in this world because, at the time, it was trying to do something that hadn't really been attempted before. Not at this budget, anyway. The game was trying to take a viewpoint most commonly employed to put you looking down the sites of a gun, and expand its potential in every direction, creating a platforming gauntlet in which you could jump, roll, and generally fling yourself across the landscape without ever leaving the confines of your character's own skull. It was wish fulfilment, really, like all the best magic: here's what life on the rooftops looks like, here's what the life of a champion gymnast feels like. Even the disasters come on like sensory victories, each plummet to the streets after a missed ledge building a wonderfully exhilarating kind of terror within you before the unseen impact. Ta-da!

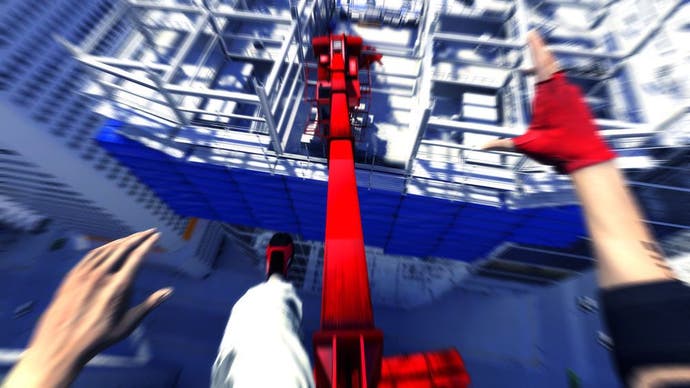

When it works, it's in part because of the closing of the doors. This is a game that sacrifices a face button just to give you an easy in-game means of finding your destination, since any dropping out to a map, or even a glance at a radar, would break the spell. The levels, too, take the white box stage of game design and turn it into a genuine aesthetic: stark white buildings that, on closer inspection, have a wonderfully subtle roughness of texture to them, that offer a sense of the sterile dystopia the game is trying to depict, that clue you into your potential route forward by staining useful parts of the landscape a bright fire-engine red.

Those bursts of red - or Runner Vision - lead you by the nose, working together with the broad horizons to create a sense of expansive freedom in a game that actually offers very little of that. The doors have been closed, remember? Venture away from the optimal route and you'll frequently discover that it's the only real route, chainlink fences barring your way, prop doors resistant to every thump. Is it a shame to be hemmed in? Not really, because Mirror's Edge is bringing in the track a little so as to have more control over the corners: rather than allowing you to dawdle and sound out the hidden possibilities of the environment, it wants you to speed up and tackle your problem-solving at 100 miles an hour. Can you clip together your ducks and tucks and rolls and jumps until there are almost no gaps in between them? Can you build momentum until you can barely feel your feet on the ground anymore, until it feels like you might be flying?

Tellingly, when Mirror's Edge falls down it's because the designers didn't close enough doors. Interior sections tend not to work as well as moments when you're back on the rooftops. The sizes of the buildings you're moving through feel too pokey to house your expansive moveset, the objective button often leaves you pointed, stupidly, at ceiling tiles or a square of industrial carpeting. And besides, the central pledge isn't as strong. I don't want to be ducking around desks and clambering over gantries - I want to be back out there, leaping between skyscrapers.

Combat, too, is probably an avenue that should have been blocked off. It sounds great on paper - guns are powerful but slow you down, bullets are uncommonly deadly - but in reality it feels like a vestigial element, a clutter of old ideas that the rest of the game has outpaced.

Finally, tying both of these things together is naff story, a dull tale badly told. Do you really need much of a narrative drive to push you towards the next slide, the next jump? Do you really need a voice, even, to go along with such astonishing abilities? If Mirror's Edge's designers really are magicians, they need to work on their patter.

Still: small change, really. Mirror's Edge met with a fair amount of confusion when it was first released. It seemed like a step towards something interesting, but close up it was too easy to see all the moments its confidence faltered. Now, though, returning to it after the years have passed, it's a lot easier to forgive those lapses. Beneath the hedging of combat and conspiracy thriller, this is a brave game and a bold one. It's a leap into the unknown, and for once, that's no trick.