Three years on, how does Bioshock Infinite hold up?

A thousand doors to nowhere.

It's a peculiar sensation, looking back at another version of yourself and thinking "really?". BioShock Infinite was one of the very first games I covered professionally. I recall enjoying it at the time, but haven't thought about it much since that initial playthrough due to the tsunami of games that have demanded my attention since. Yet as I am about to take an extended break from both gaming and writing in anticipation of the birth of my daughter, I felt a strong urge to revisit this particular landmark in my life, as a form of taking stock, I guess.

After playing Infinite through a second time, I dug out my original review of the game (written for Custom PC Magazine) and was surprised to find myself describe it as "the pinnacle of what the mainstream FPS can offer." Three years down the line, I couldn't feel further from that assertion.

I can understand where I was coming from. In terms of its ambition, BioShock Infinite is a shooter that's second to none. How many other FPS' do you know that attempt to tackle themes ranging from religion to the physics of spacetime, that addresses topics such as racism and the oppression of the working classes? I also still believe that, as an FPS, it's a fun one. When it all comes together, the skyrails, Vigors and tears all make for some colourful and dynamic combat.

But the central problem with BioShock Infinite is that it so rarely does come together. Like the City of Colombia itself, Infinite is a drifting archipelago of ideas held together by the flimsiest of connections. What we see when we play Infinite is a glimpse of a much larger and more cohesive game that was ultimately chopped up, thinned out and stapled back together in order to ship a product.

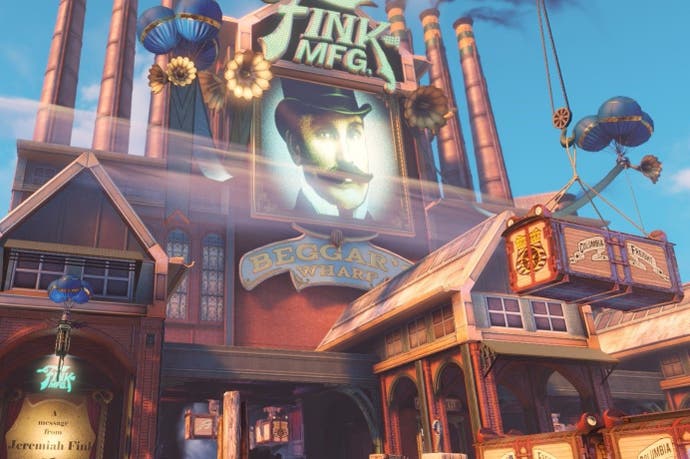

Nevertheless, Infinite still has the capacity to wow, certainly at the beginning, presenting us with a clever inversion of the original BioShock's introduction. Whereas the first game's protagonist crashed down from the sky and descended into Rapture, Booker DeWitt, ascends from the ocean into Zachary Comstock's floating utopia. There's magic in Columbia's initial reveal, its gently bobbing buildings framed against a backdrop of brilliant blue sky. Colombia is devoid of the grim horror that ravaged Rapture. Instead, attractive, smartly dressed couples chat idly on park benches, while a barbershop-quartet sings arrangements of modern tunes standing atop a flying gondola. It's sweet to the point of being saccharine, a peaceful and devout candyland for American exceptionalism.

It isn't long however before Colombia reveals its ugly side, at a fairground where onlookers throw baseballs at a mixed-race couple. In return, DeWitt reveals his own ugly side in explosively violent fashion. It's also here where the seams of Infinite become visible for the first time. At this funfair the player is introduced to Vigors, rehabilitative tonics that imbue the drinker with magical powers. They're Infinite's equivalent of BioShock's Plasmids. But they lack the same grounding within the world. How precisely do they work? Why do so few of Colombia's inhabitants use them when they are so readily available? And how come they haven't resulted in the same downfall of society that BioShock's Plasmids caused? Infinite's Vigors seem to exist for one reason - BioShock had them.

As the game progresses, more such inconsistencies reveal themselves. The skyrails, great arches of suspended metal which are ostensibly used to travel between islands, and looked so impressive in early footage of the game, are more often than not limited to tiny closed loops that bear little resemblance to their initial presentation. This, coupled with the fact that Infinite is a strictly linear experience that nevertheless offers the player side-quests, appear to be the lingering ghosts of a larger game.

At least the skyrails are still fun to play with, which is more than can be said for the Tears. These are windows into parallel universes which can be opened by DeWitt's companion Elizabeth. Think what you could do with such a power! You could kick an enemy into a land filled with dinosaurs, or drop a spaceship onto an opponent's head. Infinite's interpretation? Gun turrets, medkit stations, and cover. Could it be any less imaginative? There's nothing wrong with the tears functionally. But dressing up bog-standard FPS conventions as something brave and innovative is the definition of pretentious.

Thematically, Infinite is similarly scattershot. As I already mentioned, we're introduced to Columbia's racism early on, and the game hammers this theme home repeatedly in the first half. An entire section takes place inside a propagandist funhouse that celebrates Comstock's victories at Wounded Knee and during the Boxer rebellion. Here, gurning cutouts of Chinamen and Native Americans pop out of the scenery at DeWitt. "Cruelty can be instructive" asserts Comstock when discussing the topic of exiling and denying votes to ethnic minorities.

Yet while Infinite's portrayal of racism is both vivid and eloquent, it has no greater depth than those cardboard automatons. It is never explained why a floating utopia run by rampant xenophobes tolerates ethnic minorities at all. Are they needed to do the dirty jobs that keep Colombia afloat? Does Comstock begrudgingly accept their presence to keep fear of the "other" alive in the collective mind? The ultimate takeaway from all this is that racism is bad, which is hardly insightful.

Finktown's evocation of working class oppression fares a little better, even if it does hit like a brick to the teeth. The sprawling factory complex populated by robotic lines of workers, toiling to the sound of Fink's cheerfully veiled threats, brings to mind similar images depicted in Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times. Fink pays his employees in coupons for his own stores, and auctions off jobs with candidates bidding for them in their own time efficiency. Colombia has even perfected the capitalist drone in the form of the Handyman, a human head attached to a lumbering mechanical body capable of working tirelessly.

Although garish, Infinite deals with this rarely-explored idea in games fairly well. Unfortunately, the entire enterprise is undermined by Infinite's appallingly simplistic portrayal of the rebellion that boils up beneath Finktown. Within the space of a couple of hours, we see Daisy Fitzroy go from downtrodden leader of the Vox to blood-crazed psychopath, smearing her face in the blood of the fallen Fink, and even threatening to murder a child on the grounds that he'll grow up to be another despotic aristocrat.

Hence the only non-white character Infinite lends a voice to becomes the exact kind of monstrous caricature portrayed in Comstock's House of Heroes. We also hear DeWitt repeatedly emphasise that there is no difference whatsoever between Comstock and Fitzroy, which is an astoundingly asinine assertion. Criticising a bloody uprising is fair enough, but to tar racism and revolution with the same brush and then dismiss the entire topic? That isn't just oversimplification, that's verging on cowardice.

It's difficult to know for certain how much of the Infinite we see is the game that Irrational originally intended, and to what extent its flaws are a consequence of the changes Irrational made. But there are plenty of clues that indicate what 2K eventually published was a compromised vision. Infinite endured a lengthy and allegedly turbulent development, delayed twice and suffering several high-profile departures in the year prior to release. In the latter half of development, Irrational hired Epic Games' Rod Fergusson, who was known in-house as the "Closer" due to his intended purpose of getting Infinite out of the door.

Game developers would argue that most mainstream projects are difficult developments in one form or another. But where things get interesting with Infinite is in the repeated references by the designers to the amount of content cut from the game. Levine himself stated to Ausgamers that two games' worth of content were removed from the final version, while art director Scott Sinclair upped the estimation to five or six while speaking to Play magazine.

We even have a window into how Infinite changed over the course of the project. The demo from E3 2011 shows us a sequence of events that were scattered right across the game in the final version, from Elizabeth opening a tear to a 1980s Paris, to Songbird stalking outside a building while Elizabeth and Booker cower inside. There's also an extended battle with the Vox Populi that takes place in an environment far larger than anything we witness in the final game.

But I don't think we can dismiss Infinite's problems so simply. Half Life 2 was another shooter that dealt with big ideas, emphasised companionship with a sidekick, and was merciless with the editor's scissors during development. But Half Life 2 really is the pinnacle of what the mainstream FPS can offer. So what did Half Life 2 get right that Infinite gets wrong?

The answer lies in Infinite's storytelling, and its determination to upend the player's sympathies wherever they land. Half Life 2's revolution was led by lovable rogues, goofy scientists, and a security guard with a cat complex. It invests us in its characters, and hence makes us care about the events that unfold. It may not be as high-minded as Infinite is, but it doesn't forget to lay the groundwork that gives the player reason to pay attention.

In contrast, I cannot think of a single likeable character in Infinite. Both Comstock and Fitzroy are thoroughly detestable. The Luteces' clipped and condescending dialogue quickly begins to grate. DeWitt might sport the rugged jawline of Indiana Jones, but the charm is gouged out in favour of sneering misanthropy. Even Elizabeth, Comstock's doe-eyed talisman, cannot escape the plot's determination to see her miserable and corrupted, switching within heartbeats from childish naivety to adolescent pouting and, finally, weary resignation. In my second play-through the only character who provoked a strong emotional response in me was Songbird, Elizabeth's gigantic avian jailer whose possessive love for her tragically suffocates them both.

Infinite is so obsessed with pushing the plot forward, on giving you vigors and skyrails and tears, contemplating religion then racism then capitalism then socialism then quantum physics, that its characters and relationships never get a chance to blossom. Whatever happened during those five years at Irrational, at some point down the line the heart was cut out of Infinite, resulting in a shooter that ponders an awful lots of subjects, but doesn't really care about any of them.

BioShock Infinite is a game that wants to have its cake and eat it, and rather than accept its limitations, rips a hole in the fabric of reality to do so. It's gaming's loftiest and most spectacular folly, a monument to the mad extremes this industry will sometimes go to in search of a better version of an idea already explored to exhaustion.