Comparing the cityscapes of The Witcher 3, Dark Souls and Bloodborne to medieval paintings

A Song of Towers and Battlements.

Mention the city in the middle ages, and you likely either conjure images of streets awash in faeces and offal, or of a cosy collection of quaint houses reminding people of gallant knights and ladies. Even though cities harking back to medieval times have been a staple of fantasy games ever since the inception of the genre, they usually do little to challenge the clichés presented by Renaissance fairs or grimdark pseudo-realism. To make things worse, those sterile spaces function primarily as pit stops for the player, a place to get new quests, to rest, or to trade. It's difficult to imagine everyday life in those places once the hero is out of town. They're little more than cardboard cut-outs (I'm looking at you, Skyrim).

A handful of games, however, try to paint a more interesting picture. The Witcher 3 boasts a handful of cities that would be exemplary in any medium, but, being found in a video game, have the additional advantage of being able to invite players to intimately explore and study them from every angle. Cities like the central European Novigrad or Oxenfurt, or the Mediterranean Beauclair are vibrant places whose fundaments are firmly grounded in the middles ages despite their more fantastical aspects.

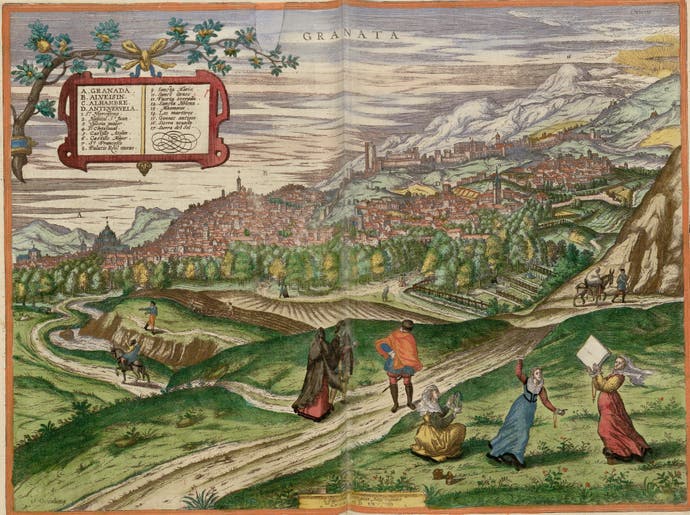

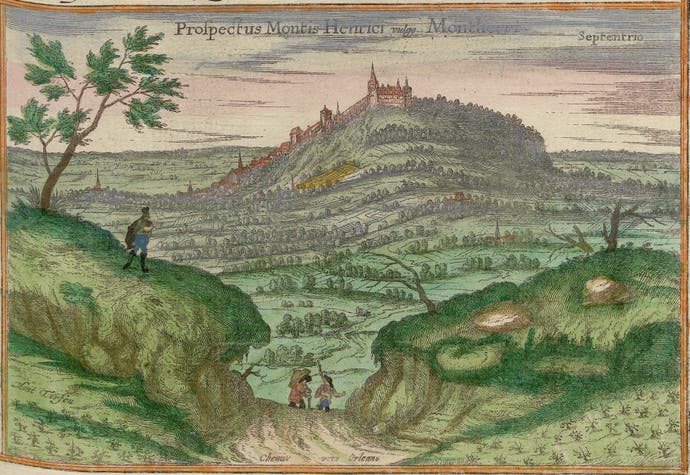

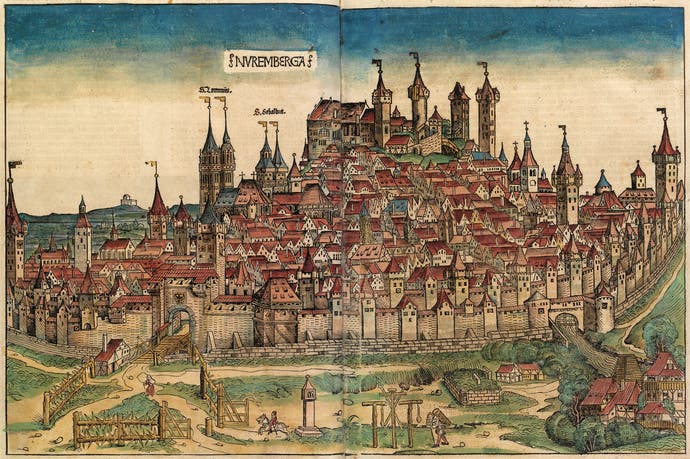

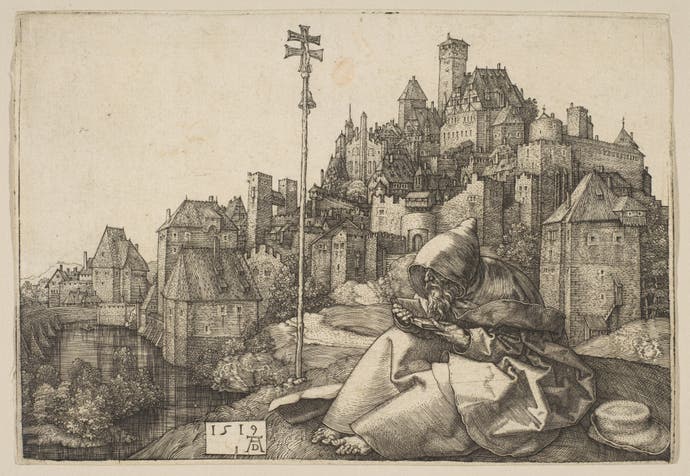

The cityscapes of The Witcher 3 resonate with illustrations from the 15th and 16th century. Good examples are the Nuremberg Chronicle or the Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cities of the World), a large collection of engravings of cities from all over the known world created by the cleric and geographer Georg Braun and artist Franz Hogenberg. Some of these depictions function as maps, but most simply try to capture the character of a given city, showing it from a low bird's eye view that creates a strong profile and a sense of totality. They're flattering views that emphasise a city's verticality, that is its countless towers of fortifications and cathedrals that emerge in the profile, as well as the way those cities have grown out of or into their natural and agricultural environments. Often, people in colourful attire linger in the foreground, giving both a heightened sense of scale as well as an impression of everyday life in these places.

All of this holds true for The Witcher 3. Approaching a city even from a great distance, one is immediately struck by the imposing heights of walls and towers. The palace of Beauclair or Novigrad's Great Temple of the Eternal Fire are built on top of natural hills and exude power through their symbolic dominance of the surrounding landscape. Speaking of landscapes: one of the ways in which The Witcher 3 really shows other games how it's done is the 'fuzziness' of its cities. Yes, each city has its walls, but they never simply separate urban from natural landscapes. Instead, these spaces blur into each other. Just as seen in many of Braun and Hogenberg's engravings, the cities of The Witcher 3 gradually transition into suburbs, agricultural areas, and finally mostly untouched wilderness. The cities are spotted with trees, and buildings are scattered in the far-flung greenery.

Another aspect worth mentioning are the humans (and sometimes animals) that breathe life into these places. In Braun's engravings, we see people from all walks of life reading, wandering, transporting goods, or simply immersed in conversations. Whether you're outside on a field and in the market square, you'll encounter people at work and at play, swiping the floor, sawing wood, drinking or playing games. It may not be quite as lively as, say, the topsy-turvy paintings by Bruegel the Elder, but it does succeed in giving an impression of a lived-in space that exists, moves and thrives independently of the player.

The cities of The Witcher 3 may exist in an often cruel and callous world, but they're not portrayed as cesspits. Instead, they capture some of the wonder and grandeur expressed in medieval depictions. There was a well-established poetic genre called 'Städtelob' (German for cities' praise) which celebrated a given city for anything from its battlements to its citizens. The world of The Witcher 3 is more complicated than this idealised view, but you may well imagine this sort of poetry existing within it.

The Witcher 3 may be a fantasy game, but its cities are down-to-earth. Other games present more wonderful cityscapes, and one of the most interesting can be found in Dark Souls: Anor Londo, city of the gods. It is a hidden, mythical place whose presence can at first only be guessed at by distant walls on high mountains reaching towards a canopy of grey clouds. As soon as you get there, after an arduous ascent and the subsequent transportation by 'angels', it is clear this place is unlike anything that came before. It isn't just the brilliant light that suffuses the city and seems blinding after dozens of hours of stifling darkness; Anor Londo is also the first place in Dark Souls that offers you a total panorama, and a real cityscape. Anor Londo is a beautiful place, but it is this sudden, extreme contrast to what came before that makes your arrival there truly breathtaking. You've crossed a caesura, ascended to a higher plane of existence.

Anor Londo is a holy place and a testament to a cosmological order symbolised by its elevation and the (illusion of) sunlight. Its white stone and countless towers, arches and flying buttresses in the Gothic style, too, seem to claim divine legitimisation and power. In some ways, Anor Londo mirrors New Jerusalem, or Heavenly Jerusalem, a fantastical city prophesied to descend down to earth after the establishment of the kingdom of God. An illustration in the Liber Floridus (around 1100) imagines this heavenly city as a place of white and blue stone, dominated by towers and walls.

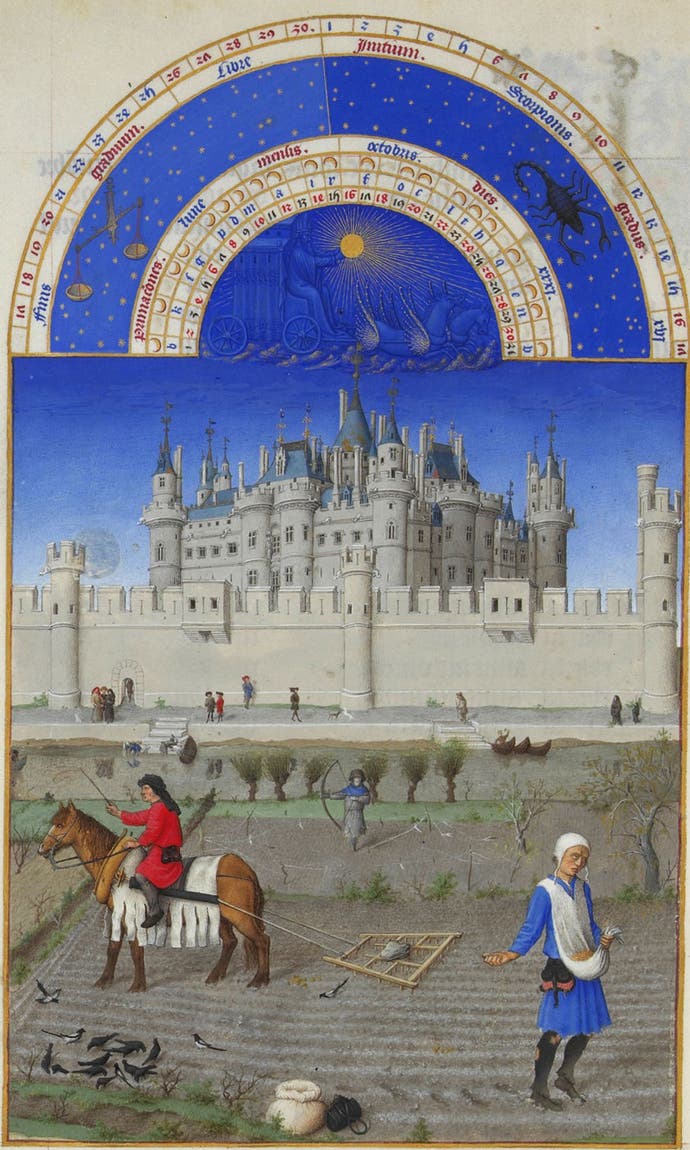

Of course, actual architecture tried to claim to be part of a divine order, too. This is especially clear in the 15th century illuminated manuscript called the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Quite a few of its calendar pages depict enormous palace complexes of white and blue stone as imposing mediators between the peasants and their fields below, and the sun and star constellations above.

Anor Londo isn't a 'historically accurate' city in a narrow sense, but it is authentic in the way it channels medieval ideas about power, architecture and the heavens. A similar argument can be made for the urban sprawl of Bloodborne. Yharnam is a multi-layered, historically ambiguous place with strong Victorian influences running through it, but the medieval still peeks through the smoke and haze in the form of Gothic cathedrals, palaces and suburbs. It is a city with monumental architecture and twisted figures shrouded in darkness, punctuated here and there by fire. It doesn't bring to mind traditional medieval interpretations of hell, but there certainly is a kinship to the darker side of the paintings of the infamous Hieronymus Bosch. Here, we see villages engulfed in fire, and indistinct architecture in an almost pitch-black hell with barely enough light to reveal the outlines of enormous buildings and sinister figures. They look like places where a hunter might find some work.

These are just three examples of fantasy games that draw from aspects of medieval art, imagination and politics and rework them in their own cityscapes. Still, there's plenty of untapped potential in the artefacts left behind by the medieval world, and we don't have to go far to find them. I for one would welcome a fantasy game that models its cities after Bosch's wonderful and bizarre visions of heaven: