The history of bleem!

How a small tech startup won the battle but lost the war for software rights.

As retro game prices continue to rise and old games become lost to time, emulation is an increasingly popular option for players looking to sample the classics. And yet, while their use is legal if a little murky, emulators are generally frowned upon by video game publishers, and remain the preserve of hobbyists. But what if you could go into your local game store and purchase an emulator commercially that allowed you to play games from rival formats on your PC or console? In the late 1990s, that actually happened, when a west coast tech startup named bleem! tried to take on a gaming giant.

The death of Connectix

To understand the impact bleem! made, we have to turn back further to a company called Connectix, a large player in the Apple world in the 1990s that had achieved success with its Virtual PC product in 1997, a virtualiser designed to run Windows on Macintosh systems. In 1998, Connectix had approached Sony to help design its follow-up product, a PlayStation emulator for Macintosh computers called the Virtual Game Station (VGS), but Sony declined, leading Connectix to reverse-engineer the PlayStation BIOS independently of Sony's involvement.

The VGS was publically announced - complete with endorsement from Steve Jobs - at the annual MacWorld expo in January 1999, and released shortly thereafter, receiving much industry attention.

The VGS had barely released before incurring the wrath of Sony Computer Entertainment however, who sued Connectix for a number of perceived copyright and trademark infringements just three weeks after the MacWorld announcement. Sony was initially granted a preliminary injunction against Connectix by the Ninth District Court in April 1999 that prevented sale of the VGS due to its use of the PlayStation BIOS as part of the company's reverse engineering process.

Connectix fought against this, and in February 2000, the Court of Appeals reversed the original ruling, lifting the injunction after deciding Connectix's use of Sony's BIOS was protected under fair use, a decision that lay significant groundwork for the protected status of emulation in the US legal system. In addition to reversing the injunction, the Court of Appeals also reversed the District Court's trademark ruling, which had claimed Connectix tarnished the PlayStation brand by releasing what Sony considered an inferior product.

On May 16, 2000, the San Francisco District Court also threw out seven of Sony's nine copyright and trademark claims against Connectix. It started to seem like the company was increasingly in the clear; the only two allegations left for Connectix to defend against were claims of unfair competition and trade secrets violation. In addition, Sony also sued for patent violations, which imposed harsher rules regarding IP use than copyright laws. These issues were due to be addressed in court by March 2001, but just before this could occur, Sony and Connectix came to an agreement and the VGS was folded into Sony Computer Entertainment. Sony, realising they had no effective case against Connectix for copyright and trademark violation by this point, had simply bought them out.

Connectix and Sony presented the agreement as a 'joint technology venture' to the press, and Connectix head Roy McDonald expressed excitement at the potential for future collaboration. Following the agreement he stated that Connectix "would gain access to technical resources at Sony that we've never had before [and gain] new cash resources that will enable us to fund new projects." Despite this enthusiasm, McDonald's hopes would not come to fruition-SCE never went ahead with any plans, and Connectix eventually dissolved in August 2003.

The origin of bleem!

bleem! was a company based in Los Angeles that, in a similar fashion to Connectix, became notable for its release of a commercial PlayStation emulator, leading to a series of high-profile lawsuits involving Sony Computer Entertainment.

Initially, bleem! consisted of just two people; programmer Randy Linden, who had become a notable talent for his work on technically demanding game ports, including Doom for the SNES and Dragon's Lair for the Commodore 64, and David Herpolsheimer, an expert in the hardware and software marketing world who had worked with clients such as IBM, Kodak and Apple.

Linden came up with the initial concept of a PlayStation emulator for the PC, and contacted Herpolsheimer to ask if he wanted to get involved. Herpolsheimer agreed, and thus bleem! was born.

The pair started working out of their homes, Linden in San Diego and Herpolsheimer in LA; no investors were involved in these early stages, but once the bones of bleem! were in place it started to go through an extensive beta period.

"It was a very organic, grassroots kind of startup: Randy had an idea; and I knew I could get it to market," says Herpolsheimer. "But we were still just two guys: no funding, no staff, no advertising budget, no fancy offices with Herman Miller chairs.

"If it weren't for a small group of hardcore games who volunteered to help us beta test, and literally thousands of gamers in forums and chatrooms who followed their posts and told their friends, bleem! never would have made it off the ground."

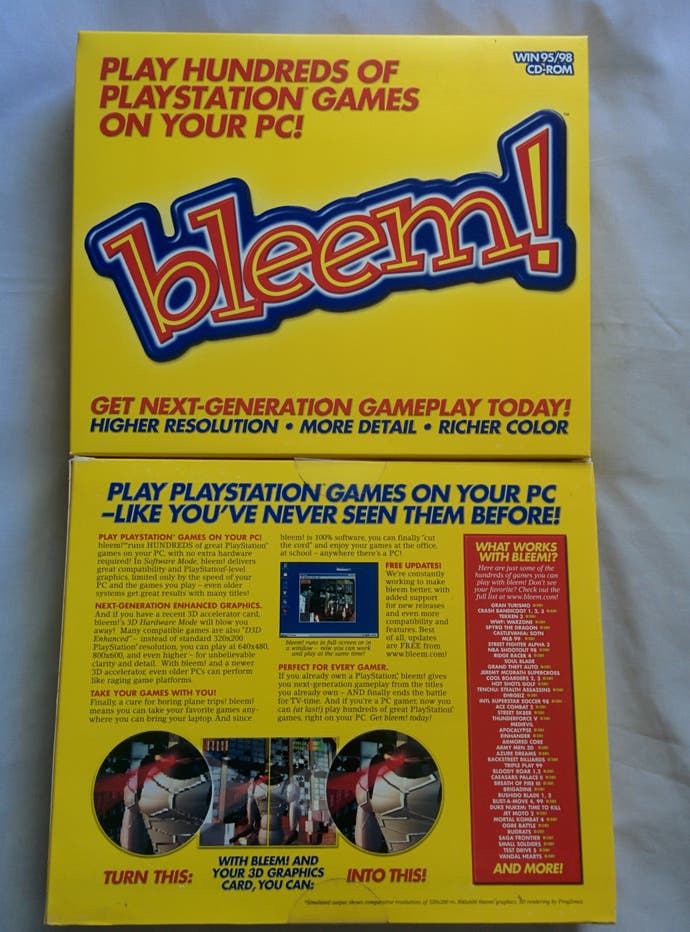

bleem!'s first stab at the product, called 'bleem! for PC', was funded following a proto-crowdfunding, pre-order campaign. It first released as an online beta in March 1999, and a few months later as a retail CD-ROM release, with initial orders shipped out of Herpolsheimer's garage. Priced at $29.99 in the US (the average cost of a PlayStation by this point was around $99), bleem!'s primary selling points were that it allowed PCs to not only recognise and play PlayStation games from an extensive list of compatible titles, but also play them with improved visual fidelity. It was an impressive effort, but couldn't play every game flawlessly and included some glitches.

Although initially attracted to the project due to its business opportunities, bleem! became something of a passion project for Herpolsheimer, an early advocate for digital rights in a time when the DMCA hadn't fully considered the ramifications of the internet and the concept of digital ownership. Having played his first console in 1975, he came from a gaming background of floppy discs and EPROMs - closed content, usually delivered on cartridges, each with individual patents and made by software developers more often than not tied to licensing fees. Game cartridges were effective at combating piracy, but they eliminated user choice by being tied to a single format. After all, the method of playing a VHS, cassette tape or audio CD wasn't restricted by manufacturers, so why should a video game? When a console died, the software was gone - there was no future-proofing in place, and this was something that frustrated Herpolsheimer.

When the Sony PlayStation became the first CD-ROM based console to achieve mainstream success, breaking the barriers that had befallen other attempts such as the earlier Panasonic 3DO, Sega Mega-CD, and PlayStation's contemporaneous rival, the Sega Saturn (which had already failed in the US market by 1998), he saw an opportunity for preservation. To the bleem! team, the format for content delivery was of relative unimportance; it was the right to play content as the owner saw fit that they were striving toward.

This was considered the central philosophy at the heart of the company. By the time bleem! was taking off the PlayStation had already amassed a huge library of games, and as such was considered a perfect starting point for the company to focus on.

The timing of bleem! in the wake of the Virtual Game Station lawsuits was, according to its creators, a coincidence - they had no knowledge of Connectix's project when bleem! development started, reflected by the fact that Linden had used a different method of emulation than the VGS that did not make use of Sony BIOS or violate any other copyright.

VGS was considered a 'virtual machine'; a software version of a PlayStation. bleem! differed from this in that it used a method, coined by Linden as 'dynamic recompilation', which involved writing subroutines that recognised certain types of functions on the fly, then recompiled them in a way that could be understood by the hardware of the chosen machine. This was the process that allowed for bleem! to go further than Connectix's VGS had, with support for increased resolutions, anti-aliasing and even transparency effects, such as the glow of a fireball or the smoke from car tyres.

"bleem!'s higher resolutions, texture filtering, and anti-aliasing all made games feel much more realistic," says Herpolsheimer. "You were getting a taste of next-gen gameplay long before the release of the PlayStation 2."

Initially, the bleem! team did not consider themselves to be stepping on Sony's toes. The Sony PlayStation released under a traditional razor and blades model, selling consoles at a list price lower than production costs and making up for hardware losses from game sales. Since Sony was making a loss on new consoles but profits from game licence fees-loss-leading being a fairly common tactic in the game console industry-its business model relied on a solid software attachment rate. bleem! felt that they could offer a cost-effective, pro-consumer method of expanding Sony's software portfolio to the PC system, thus circumventing Sony hardware losses.

"We saw it as a positive for everybody," explains Herpolsheimer. "bleem! would instantly make hundreds of PlayStation games available to tens of millions of PC users. That meant that game developers could reach a vastly larger audience at zero cost, at a time when the PlayStation's lifespan was coming to an end.

"Consumers who owned a PC and PlayStation could enjoy the games they already owned anywhere, with improved graphics and long after the PlayStation came to an end. PC gamers could purchase and play games they never had access to before. And Sony would receive licensing fees for each and every game sold for use on bleem!. It was win-win for everyone."

As bleem! continued to take off, the team became more ambitious, continually expanding on its list of compatible games. The company purchased near enough the entire PlayStation library, from the biggest hits down to obscure Japanese and EU exclusive releases, culminating in a library of about 1000 titles being played by a full-time crew of around 20 testers.

The team had high hopes for the future. A long-term goal of the project was to turn bleem! into a mastering tool in order for software developers to port titles more easily, a streamlining process that would make developers' software ubiquitous and not tied down to a particular system. As developer tools at the time were particular to each console, there was no incentive for console companies to make it easy to port content from one platform to another.

bleem! envisaged a future where it could function not just as a generic application allowing PlayStation games to run on PC, but in addition act as a low-cost shell that a developer could add to an existing PlayStation game, allowing them to market their titles for the PC just like any other port. This idea was eventually abandoned due to worries over legal issues, since the compiled PlayStation game would have relied on Sony's development tools for this to work.

The lawsuits begin

On April 2, 1999, shortly after bleem!'s beta launch but a few months before physical launch, bleem! got hit with a Ninth Court claim by Sony Computer Entertainment citing several copyright and trademark violations. Initially, bleem! was expected to fold given its bit-player status - it was a small company with less wherewithal than Connectix - but instead, they decided to fight back.

(It is worth noting here that Sony Computer Entertainment did not respond to comment for this article. In addition, SCE chief legal officer Riley Russell, who aided during the lawsuits against bleem!, declined to be interviewed.)

bleem! turned to a young and talented lawyer named Jonathan Hangartner to help represent them in court. Once the team's legal troubles with Sony started they could not afford the services of his firm anymore, but such was Hangartner's belief in bleem!'s project that he decided to start up his own independent firm in order to represent them in court of his own volition.

Much to Herpolsheimer and company's chagrin, Sony had not actually investigated the technical specifications of bleem!'s emulation, and after some research the team discovered that Sony had simply sent out the Connectix complaint with some minor alterations. Sony, who had amassed ample evidence in its time fighting Connectix due to initial discussions with the company to license the VGS, had changed the name of the defendant from 'Connectix' to 'bleem!', while also adding the term 'upon information and belief' in order to cover themselves from being challenged on the veracity of its accusations.

"They just thought they could knock us out," explains Herpolsheimer. "Connectix was big in the Mac world, an established company-we were just two guys working out of our homes so they thought we'd just disappear. They didn't even bother to call or research, it was just the exact same statement with the names changed."

The majority of Sony's claims against bleem! were discarded by the Court, leaving just a single issue that prompted further debate. Sony claimed that bleem! had violated trademarks due to the use of PlayStation screenshots on its CD packaging to highlight the improved graphics of the games on PC, a tactic Sony claimed was a misuse of its IP. bleem! initially lost this round at the district level, with the court granting Sony a preliminary injunction, but eventually this was overturned by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The main catalyst for the court's decision to overturn bleem!'s loss in this instance was that under fair use, a competing company could in fact use screenshots to highlight the superiority of a product. Judge Charles Legge - the same judge from the Connectix case, incidentally - explained his decision in a court ruling, stating that while bleem! had used Sony's copyrighted material (i.e. the screenshots of its games) for commercial purposes, the comparative intent of the advertising "[redounded] greatly to the purchasing public's benefit with very little corresponding loss to the integrity of Sony's copyrighted material".

After the retail release of bleem! for PC, Hangartner and Herpolsheimer were joined in their fight by general counsel Scott Karol, now better known as a film producer in Hollywood. He had been friends with Herpolsheimer since childhood, having grown up with him in Las Vegas, and before joining bleem!, worked as an executive vice president at the Turner network station TNT.

Though Karol had never been a litigator, he and Herpolsheimer also got involved with the defence in order to stand a better chance against Sony, Hangartner making the court appearances while Karol and Herpolsheimer researched and assisted with briefs and strategy.

"They couldn't get their heads around the fact that we hadn't done anything wrong," explains Karol. "If you buy a copy of a copyrighted work, shouldn't you be able to play it on anything you want to play it on, whenever you want to play it? Wasn't that the whole basis of the DMCA?"

bleem! also had reason to believe Sony was attempting to derail them in the marketplace through the influence of video game retailers. With the PlayStation 2 on the horizon, and limited allocation for the new console, competition among retailers was fierce.

bleem! by this point had deep market penetration in North America, Europe and Asia, and was being sold in stores such as Wal-Mart, Fry's, Best Buy, Target, Babbage's, and many more. It was believed among the bleem! team that Sony was pushing for retailers not just to not carry bleem! in order to secure their PS2 orders, but in addition, settle the emulation debate in perpetuity.

In December 1999, Sony served subpoenas to 10 of bleem!'s biggest retail customers without giving sufficient notice to bleem!. Hangartner was quoted in a press release on this at the time, stating that "these subpoenas have nothing to do with potential damages; they only serve to scare bleem!'s vendors into thinking they might be Sony's next target." The information Sony was asking the retailers to supply was considered by the Court to be irrelevant to the case.

"Back then, I absolutely believed Sony did that," explains Sean Kauppinen, former head of marketing and PR at bleem!. "I heard about a truck in France that was seized because some accusation was supposedly made and there was a court injunction that stopped the truck. That ruins your income stream and cash flow. I'm pretty sure bleem! was killed by Sony, but that's my opinion."

Kauppinen met Herpolsheimer and Karol in Puerto Rico in 1999 at a conference designed for tech companies seeking retail and distribution in LATAM-speaking territories. He became attracted to working with the pair after seeing them demo Gran Turismo and Tekken 3 running on bleem! software, which left a strong impression. He was hired by bleem! to help with public perception in the fight against Sony.

"If bleem! had survived, emulation and backwards compatibility would be a generation further ahead. It's here, but it would be more accepted if we had been able to hold out," he explains. "When you are deposed and you see your testimony later used in defining the DMCA, it probably has some effect. I know my favorite result was meeting [Napster founder] Shawn Fanning years later and talking about what happened with Napster and bleem!. We felt we were part of something defining for a generation of digital citizens."

bleem! for Dreamcast

A few months after bleem!'s PC release, a notable shift in the console hardware space was marked; the US launch of the Sega Dreamcast in September 1999. While it would eventually become known as the publisher's last gasp in the console market, hype was high for the technologically advanced console, and there were murmurs of Sega making a comeback following the failure of its Saturn system (in the NA and EU markets, at least). The Dreamcast, with its 480p resolution and 3 million polygons per second performance, was significantly more powerful than the Saturn, PlayStation and N64, and marked the start of a new console generation.

And it had a killer app. As Super Mario 64 was to the N64 or Super Mario World to the SNES, launch title Soul Calibur became a notable example of the Dreamcast's raw potential, bettering its arcade counterpart in every way and becoming one of the best-reviewed games of all time. Dreamcast also utilized Windows CE technology, a scaled-down counterpart to Windows NT.

bleem! saw the potential immediately.

So too did Sega, which was somewhat ironic given that the company had previously supported Sony in its fight against Connectix. The possibilities of creating a version of bleem! for Dreamcast did not escape the beleaguered company. First shown off at E3 in May 2000, bleem! for Dreamcast promised to deliver PlayStation games on Dreamcast that not only matched the performance of Sony's console, but by utilising Dreamcast's superior hardware, would improve on it..

The bleem! team were gifted two Dreamcast dev kits by Sega of America, who gave Linden access to, according to Karol, "more low-level information than anyone had ever seen before".

Dreamcast was the first next gen console out," explains Herpolsheimer. "It's not like we could emulate on Saturn or same-gen systems because there's an overhead. That's what made emulation on the PC and Mac possible, especially with what Connectix did, as they just had more computational power than any other processor. So when the Dreamcast came out we looked at the specs and saw how many computations it could put out compared to what we'd need for a PlayStation game. We played around with it a little bit, and thought it would be fairly easy to port to."

Once they had a prototype working, members of the team, including Herpolsheimer and Karol, were flown out to Japan to meet with Sega's board of directors, including president Shoichiro Iramajiri, presumably excited at the prospect of getting one over on the upstart rival who had thoroughly bested his company in the previous console generation.

The meeting went well, and Herpolsheimer and Karol were wined and dined over a lavish dinner. Sega wanted bleem! to work with them, and were interested in investing in the company. However the very next day, after the previous evening's indulgence and talk of contracts, Sega made a sudden about face, deciding that it could not agree to terms with bleem! unless they received a stamp of approval from Sony, a situation Sega knew was next to impossible given bleem!'s legal woes. Herpolsheimer and Karol left Japan disheartened by this sudden and unexpected turnaround, and not long after their return to the US, the news broke.

In January 2001, after three consecutive years of losses, Sega announced that it was not only discontinuing the Dreamcast, but was leaving the hardware industry entirely to become a third-party software company, a decision that allowed them to create games for other systems such as the PS2. bleem!, down but not out, released bleem! for Dreamcast (aka bleemcast!) independently of Sega in April 2001, just over two years after the release of bleem! for PC, and three months after the announcement of the Dreamcast's cancellation.

The Redmond meetings

Interest in bleem! was not limited to Sega, however. A certain American tech giant, deep into development on its then-unnamed first console, also showed an interest in the team's technology. Microsoft was interested to learn if bleem! could make PlayStation games run on its rumoured DirectX Box project.

"The way I heard it was, there was something like a competition within Microsoft at the time. Bill [Gates] had pledged a billion dollars to one of three potential projects: a game console, a mobile product, or something or other that I can't recall anymore," explains Herpolsheimer. "We worked with them to integrate a custom, fast-booting version of bleem! with Windows, so that the user experience would be as seamless and console-like as possible. Each of the product groups made their presentations, and Bill was shown what was to become the Microsoft Xbox, running Gran Turismo 2 on bleem!."

bleem! negotiated with Microsoft for months, and Herpolsheimer even flew out to the company's Redmond office for meetings. The meetings went far enough that Microsoft made an offer of $7.5 million for bleem!'s technology, but this fell through. Herpolsheimer and co. were hoping for a valuation more in line with the estimates given by their venture capital advisors, who had made claims of over $100 million based on the company's bottom line-this was the height of a major tech bubble, after all. In retrospect, Herpolsheimer admits he should have taken it.

"We had a product people actually wanted; we were in the black despite this huge lawsuit, making money with new and protectable technology, but because Sony was on the other side, people weren't going to put their name to it," he explains. "What we didn't plan for was how we'd continue to have enough money to win, and also the fatigue factor. It just got absolutely exhausting to run a company and a lawsuit; everyone just got burned out."

The final days

It was at this point that things began to turn even uglier. A few weeks after the release of bleem! for Dreamcast, Sony sued bleem! for patent infringement, having failed to beat them on the basis of copyright and trademark. It was the same tactic SCE had used in the Connectix case.

Though Hangartner had enlisted additional counsel to advise on patent issues, and Herpolsheimer had performed considerable research into such laws as the patent writer for bleem!, Karol and Hangartner both found themselves somewhat overwhelmed. The fact that bleem! had covered themselves by not making use of Sony's code during the creation process did not hold up in this instance, as even inadvertent or accidental releases of similar products were not protected under patent law. By this point, SCE was simply trying to crush bleem! through litigation.

"David was a really smart guy even though he wasn't a lawyer, and after looking up the patents, we thought it was really weird; several of them weren't owned by Sony, some didn't apply to video gaming at all, and the others were really suspect," explains Karol. "Basically what Sony was doing is what they always do; they sent a letter to some small guy saying 'You violated our intellectual property, if you don't stop we'll crush you', and everyone goes 'Oh my god, I'm sorry', and goes away. But David didn't."

The bleem! team, having reached the end of their tether, decided to counter-sue Sony for anti-competitive behaviour, such as a heated and much-reported debate from E3 1999 where attending Sony employees tried to have show staff remove bleem!'s display from the expo.

bleem! for Dreamcast was a technical marvel and a legitimate threat to Sony. Like its PC predecessor, it allowed PlayStation games to be played on Sega's console with improved anti-aliasing and higher resolution thanks to Dreamcast's superior hardware and forward-thinking VGA compatibility.

Unlike the PC release however, the company came up with a plan to release separate compatibility discs for each game at a budget price of $5.99 each, ensuring near-perfect performance. Due in large part to financial difficulties brought about by Sony's patent suit however (with defence costs estimated at $1 million per patent), bleem!'s ambitions were stymied, and only three bleem! for Dreamcast discs ever saw release: Metal Gear Solid, Tekken 3 and Gran Turismo 2. Funds exhausted following protracted legal battles, bleem! shut its doors in November 2001.

The mark left by bleem! on game emulation tech was notable, but the court cases against Sony would prove its lasting legacy. It dominated the company's brief history - even the bug alert on bleem! for Dreamcast discs included a disclaimer that it could give users "a sudden, overwhelming urge to sue everyone you know in an evil quest for world domination." Perhaps things could have turned out differently for the games industry had bleem! been able to continue its work.

"The fact is, if you buy something digitally you should own it for life," says Kauppinen. "When a hardware platform dies, especially since they are mostly razor blade models, the software should still belong to those that purchased it. If the company that made the hardware isn't going to make more and support a user's access, then emulation should be legal and supported."

After bleem! folded, Linden, in a career move that initially hurt Herpolsheimer, went to work for Sony Computer Entertainment, having been advised to entertain an offer of work from them as part of the settlement. He was initially paid a fee as a consultant in order to help explain bleem!'s technology. In a twist of fate, Kauppinen would make a similar move, going on to work for the now-defunct Sony Online Entertainment from 2002-2005 as a PR lead on popular titles such as PlanetSide and Star Wars Galaxies.

Herpolsheimer, with 15 years of experience behind him, left the software industry altogether, disheartened by his experiences. "I was ready to build a bunker and fill it with canned food because if this was how the world worked, I didn't want anything to do with it."

In comparative tests viewable on sites such as YouTube, bleemcast!'s emulation is still to this day shown to be superior in some respects to that of the PlayStation 3 and PlayStation Vita.

Today, it is unthinkable to imagine a product like bleem! making it to market, but its footprint is unmistakable. Emulation is still a word spoken in hushed tones within the industry, and while the impact of exclusive titles in the current console space is diminished, true platform agnosticism remains a pipe dream. bleem!'s methods may not have worked out in the end, but its aims should be commended.