A Way Out review - humdrum crime with a co-op twist

Double bill.

A Way Out, the new game from the Swedish-Lebanese director Josef Fares and his team Hazelight Studios, absolutely insists on being played co-operatively by two players. Not just two players, but two friends. The action is followed using a clever, dynamic split-screen display that keeps the two player characters in view at (almost) all times, and the game is best experienced in local play. It can be played online, but not with strangers; there's no matchmaking and you can issue invites to your friends list only. You are, at least, granted a Friend Pass that lets your online buddy download the game and play with you for free.

So, it's not the easiest game to play. You need negotiation and co-ordination skills just to fix a time to sit down to it. It's clear that the developer really wants you to play it with someone you know. And it won't surprise anyone who played Fares' debut game, Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, to learn that he has a very specific pay-off in mind.

That game had two lead characters as well - both controlled by the one player this time, using both control sticks on the gamepad. It used this set-up to generate some gentle puzzle gameplay, but also to frame a mighty emotional hook near the end of the game, where the unique control scheme and the affecting storytelling coalesced in one unforgettable moment. A Way Out tries to do something similar, only with social dynamics rather than game mechanics. It kind of works, but - as is often the problem with this kind of high-concept game design - the pay-off doesn't quite justify the set-up.

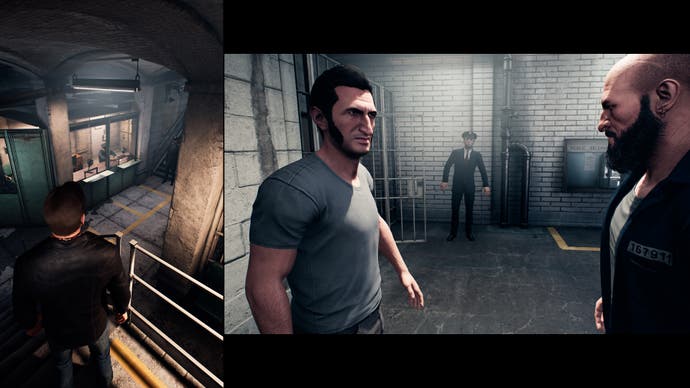

Brothers was a bucolic fantasy fable, viewed from above like a map, and the characters talked charming gibberish. It felt like a storybook or an early 90s video game. A Way Out sticks to the filial theme but offers a very different flavour of nostalgia, one that seems a more likely product of Fares' background as a screenwriter and film director. It is the 1970s, and this is a macho crime story about a couple of convicts on the run. The camera is cinematic, Naughty Dog style, and the elegant split-screen, which swooshes back and forth to change the emphasis from one character to the other or to find more dramatic framing, makes the game look like the title sequence for a vintage cop show.

If only A Way Out had the relaxed wit and style of those old TV potboilers, never mind the snowballing energy of cinema's on-the-lam classics like The Fugitive or Midnight Run. It's a stodgy, humdrum affair that rarely manages to pull its boots out of a bog of cliché. In prison, wisecracking career criminal Leo meets uptight white-collar convict Vincent. It turns out they both have reason to hate Harvey, a ruthless crimelord who double-crossed Leo and killed Vincent's brother before framing him for the murder. They fall in together and hatch a plan to escape prison, find Harvey and exact their revenge.

At first, you enjoy the methodical focus of the prison escape sequences and the novelty of a game designed exclusively for two-player co-operation. The prison setting throws up some naturally cool collaboration as one player distracts a guard so the other can sneak, filch or unscrew fittings, or lights the other's way with a torch, or discreetly passes a tool from cell to cell. It doesn't ever get tense or truly puzzling, though, and the escape itself is neither imaginative nor daring. Hiding one of you in a laundry cart is such a staple of prison escape fiction it's farcical, but A Way Out plays it po-faced, with only the novelty of the split perspective - one player peering out of a narrow slit in the cart - to give the scene any life.

It's little moments like this - that exploit the dual cameras for a visual gag or contrast, for synchronicity or repetition or an unusual perspective - that most reliably lift the game. A couple of action scenes hit their marks, notably when Leo and Vincent are cornered in a hospital and we switch to a single camera flowing fluidly from one to the other and tracking Leo side-on as he brawls down a corridor, Oldboy style. The design, writing and art, though, are uniformly mediocre. The co-op opportunities are often satisfying to pull off, but never display real ingenuity or require real thought. Fares' cinematic ambitions are a bit too much for his art budget, and the game is polished but bland to look at, drawn in olive and beige and stuffed with nondescript interiors and colourless supporting characters. After you've finished the game you won't be able recall what anyone in it looked like save the two leads.

The story's heart is the developing bond between Leo and Vincent as they steadily grow to trust each other and work smoothly together. It's well expressed in the gameplay and in the warm, understated voice work by Fares Fares (the director's brother) as Leo and Eric Krogh as Vincent. (You wouldn't guess they are both Swedes.) I wish I could say the same of Josef Fares' script, with its rote banter, clumsy sentiment and wan characterisation. His film work in Sweden was admired, so perhaps it's because he's not so comfortable writing in English that the dialogue is so flat - but that doesn't excuse the tired beats of the plot.

(Beware spoilers from this point on; I will be as vague as possible, but just as with Brothers, it's hard to talk about A Way Out without alluding to its ending. Truly Fares is setting himself up as the M Night Shyamalan of gaming, for better or worse.)

Tired it may be, but there is a sense in which A Way Out achieves exactly what it set out to do. Fares wanted to demonstrate the transformative power of telling a video game story with, and for, two players. You could almost argue that the story's stark unoriginality serves him well in this aim. There's a twist that would provoke eye-rolling in any movie, it would seem so predictable - but the co-op context, the investment that you and your friend have made in Vincent and Leo's journey, side by side, somehow make it fresh and shocking. This moment alone makes A Way Out a successful experiment in the unique and still underexplored possibilities of video game storytelling. If only the story had been worth telling in the first place.