Edith Finch and finding meaning in materialism

First-person possessive.

Seeing as it's fresh from winning the Best Game award at this year's Baftas, we thought it might be a nice moment to return to What Remains of Edith Finch and take another look at a few of the things that make it so very special.

Games thrive on curiosity: we become explorers, burning with the need to know how to beat an enemy, how to overcome obstacles and to see what waits for us around the next corner.

What Remains Of Edith Finch, much like Gone Home before it, limits this exploration to one house and manages to feel incredibly intimate. The house is devoid of life in a literal sense, but it's filled with all the things personal spaces can tell us about people. Their stories are in the items we find.

Some things are small. The whole house is littered with books. The kitchen is stacked with cook books, and while their regular appearance throughout the house simply suggests reused textures, several cartons with Chinese takeaway and canned salmon Lewis brought home from the local cannery paint a pretty damning picture of Dawn Finch's ability to cook - or at least her interest in cooking.

Despite many of the rooms having been meticulously sealed, some memories spilt out, perhaps in an attempt to impress potential visitors - such as a picture of Barbara on a film set in the hallway and several of Sam's photos throughout the house. It suggests terminal materialism, wanting to own and display certain items to impress others and to remind yourself of how impressive you were at one point or another.

This isn't particularly worrisome in small doses - like Sam's hunting trophies you find here and there. Barbara's room, however, is a startling example of how unhappiness can spread quickly when a room reflects a part of your self-definition that you need to let go of. In her small room, Barbara is surrounded by film memorabilia with her likeness on it. On the wall the Hollywood sign spells her name. A gala dress in the room is a sharp contrast to the outfit she wore to work at a diner. Barbara and her family chose to keep representing her past career at every opportunity. The Barbara her mother chose to remember by preserving her room - particularly by putting a comic onto her shrine, a last outside account, a sign of fame no matter how small - died long before the actual sixteen-year-old did.

Most items you find represent a more benign form of materialism: in instrumental materialism, items are repositories for meaning for their former owners or those who knew them. They are sentimental knick-knacks with meaning that isn't immediately apparent.

This is particularly true for the items you find at each of the shrines Edie made for each deceased family member. The shrines and the rooms overall exemplify the great pitfall of instrumental materialism, which is how easily it can lead to hoarding. The stronger the emotional connection to an item, the harder it is to get rid of. In this way, instrumental materialism isn't unlike terminal materialism, but it's often more powerful since, unlike status symbols, sentimental items never lose value. In Edith Finch, hoarding is as much a symptom of trauma as it signifies the wish to honour the history of a family who is most well-known for not being able to build much of a history at all. Edie, or Edith Finch Sr., started a new family within view of the ruins of the old one. Instead of moving out, the house turned into an architectural impossibility in order to accommodate new family members as well as the old ones, making the coexistence of happy and sad memories the theme of the whole Finch family.

To Edie, longest surviving member of the family, everything seemed worth holding on to. Some items she understandably felt pride in and wanted to preserve, such as a wooden model of the house, likely put together by her husband Sven as an actual model for the actual house, or books written by her father Odin. Other choices are questionable, such as the cages of long-dead birds or the fact that she continued to use the bathroom her grandson Gregory died in without making any changes to the décor, going so far as to keep one of his toys always in view.

While some of the rooms immediately signify the biggest passions or skills of their previous occupants, others, like Molly's, are less easy to read. At first glance, Molly's room looks typical for a little girl of ten. The walls are painted pink and the bed has a curtain shaped like a big blossom. Wooden ornaments, a golden leaf border across the walls and plants, hint at her love for nature as much as the pony toys and the gerbil cage do. The books on monsters on her shelf, the scorpion in a jar and the Pacific Ocean Depth Chart on the other hand tell a story of her fascination with some more unsettling creatures, which she will eventually turn into the night she dies.

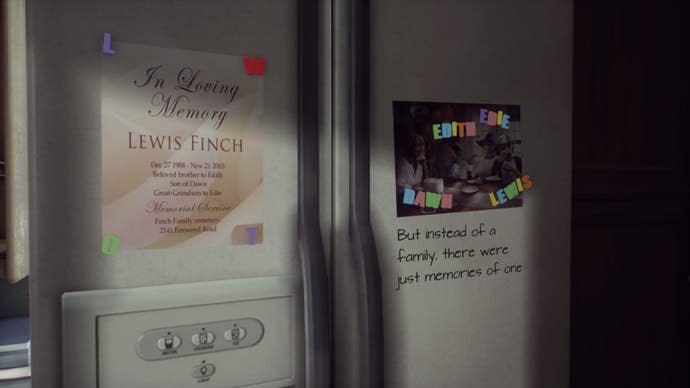

Lewis' room is similarly normal, typical for a man who hit his twenties in the early 2010s - he has a PC with a double monitor and a gaming mouse, here and there you can see some CD-Rs lying around. Even without Edith telling you, the few light sources throughout, the paraphernalia and the additional console tell you that Lewis' biggest passions were smoking, gaming and generally being left alone. It's easy to imagine him as a quiet type who talks more to people online than to his family.

This behaviour is so normal for someone his age, especially those who struggle to transition from high school to that confusing time of making career choices and pretending to be an adult, and Lewis was probably so chill all the time that it was difficult to see how hard he was taking the death of his brother Milton. The warning signs were there: all other Finches who got to spend significant portions of their early lives with a sibling before witnessing their deaths made drastic choices. Walter chose to live below ground and Sam is described as chasing death in the military. Their rooms speak of the ways in which they dealt with this. Lewis' room does not.

Sam's story runs through the Finch house like a red thread. Like his sister Dawn, he grew up in the house and lived in several rooms. He is also the only one to ever have brought a spouse to live there. Sam shared a room with his twin brother Calvin, and the setup of his half of the area is especially interesting because he lived in the room even after his brother died. With Calvin's half roped off like a museum, a clear testament to the eleven-year-old's love of space with rocket-shaped lamps, stars painted on the walls and a whole command centre of his own, Sam developed a passion of equal vigour - going to the military. His room embodies his goal at the time.

The propaganda posters in his room, as well as the fact that Sam was a teen in the Sixties tell us of a child who closely followed the developments of the Cold War and who, judging by the pictures he took during his time away, perhaps went to fight in Vietnam. It's interesting to note that his love for the army came fully endorsed by his mother: since Edie painted all the doors to her children's rooms, she probably painted the walls, too, and his is adorned by a military aircraft flying over a forest.

Eventually Sam raises his children in something akin to barracks. Each only has a bed and a locker, there's a list with daily chores and a training regimen on the wall. The sternly worded house rules next to the list of chores tell us of Sam's fear of losing his children as well as his dedication to discipline. They are forbidden from playing outside without permission or answering the door to strangers, and it's of equal importance to make no messes after dark, finish chores in a timely manner and respect each other. This utilitarian space was later abandoned, even though the remaining Finches will have had to cross it to get to their part of the house for quite some time.

This way of avoiding - yet not quite abandoning - memories is as much a problem as the way grandmother Edie clings to them. Right at the beginning, Edith makes it clear that the house you are about to enter is no home to her - she firmly calls it "the house" but changes her mind the second she sets foot in it. In home school, she learnt the story of her family, but never actually learnt about the occupants of her own house. When she enters it again, all she has are the items and the stories they tell. We get to play through her imaginings - her way of filling gaps in her knowledge, aided by her family's possessions.