Obituary: Rick Dickinson, industrial designer of the ZX Spectrum

"You had to be incredibly inventive and imaginative."

It's probably fitting that Rick Dickinson's interest in design was first kindled by Lego. Speaking to Edge magazine in 2004, the industrial designer behind Sinclair's iconic 1980s home computers, who died of cancer earlier this week, explained how toddler ambitions to be a train driver and a lorry driver were put aside when he discovered those colourful blocks with their magical clutch power. "Lego had [just] launched their brick system, in Denmark and Germany," he explained. "And since part of my family was German I used to play with Lego all the time." Building Lego bridges gave way to building Lego spaceships; the fledgling designer was already learning practical skills that would become absolutely crucial later on. "I built things out of Lego," he remembered, "but with it being a square brick format you had to be incredibly inventive and imaginative."

Lego led to an interest in architecture and then to a career in industrial design, first in-house working for Sir Clive Sinclair and eventually running his own consultancy firm, Dickinson Associates, in Cambridge. Legendary commissions and plenty of awards followed, but some of Dickinson's first projects - the design of the Sinclair ZX81 and its follow-up, the ZX Spectrum - remain his greatest legacy. These glorious personal computers, surprisingly compact and pleasant on the eye and in the hands, matched with a price point so low that it seemed, at the time, to be almost a work of magic, became a defining part of the most charismatic background clutter of 1980s Britain - a time and a place not short on pop culture clutter in general. They are a reminder, too, of the strange kind of fame that an industrial designer gets to enjoy. These people make objects that help bring our lives into focus, but they retain a blissful personal anonymity at the same time. How many children rushing home from school to fire up the Speccy - much like Dickinson had once rushed home to upend his Lego bricks all over the living room - might have passed the machine's co-creator in the street without noticing?

It was hard for someone like Dickinson to remain anonymous, however. In the same Edge interview he emerges as wonderful company: knowledgeable, fiercely engaged and gloriously opinionated. Offering thoughts on everything from the design of Commodore 64 - "Big, bulky.... No innovation.... Can I swear...?" - to the original Xbox, which he deemed "interesting" - "You're probably thinking, 'This guy's a weirdo,' but yeah, there are things I like about it" - he retained, more than anything, a supremely youthful intelligence, witty and honest and offering unexpected takes on things.

He had earned the right to his opinions. He first worked for Sinclair making calculators, under the watchful gaze of John Pemberton, during a university placement while studying industrial design at Newcastle Polytechnic. After graduating in 1979, Pemberton sent him a telegram: "Ring me ASAP". According to the story Dickinson told Edge, he immediately leapt into action and spent the best part of a day trying to find out what ASAP meant. Eventually, he got in contact and discovered that Pemberton was looking for a replacement for himself. This was "quite scary," Dickinson admitted, "as John was a world-class designer and I'd just left college."

Dickinson's first proper job involved seeing Pemberton's design for the Sinclair ZX80 through production, finding mould makers and plastic companies to execute the plans. Following the release of the machine in 1980, his first product as a Sinclair designer was a memory expansion for the ZX80 - but his first starring role was with the design for the ZX81.

Both the ZX80 and the ZX81 were enormously successful, but the design of the ZX81 is a clear step forward. The ZX80 retains a lovely retro warmth, but the ZX81 looks sharp and purposeful and thrillingly modern. Sinclair's business revolved around keeping costs down wherever possible, and the ZX81 turns this razor-edged efficiency into a genuine aesthetic. Even now, it is a strangely desirable thing. It is no surprise to read that it won the Design Council award upon its release in 1981.

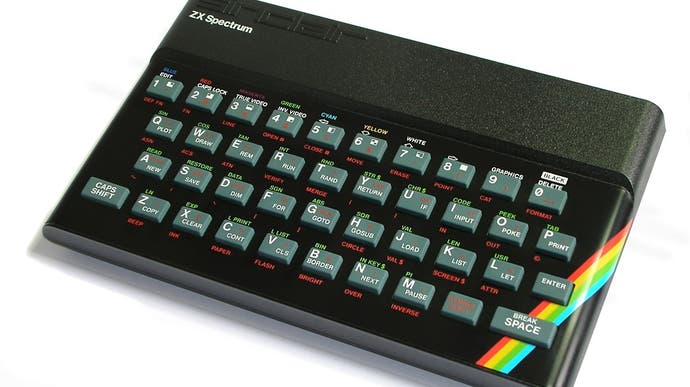

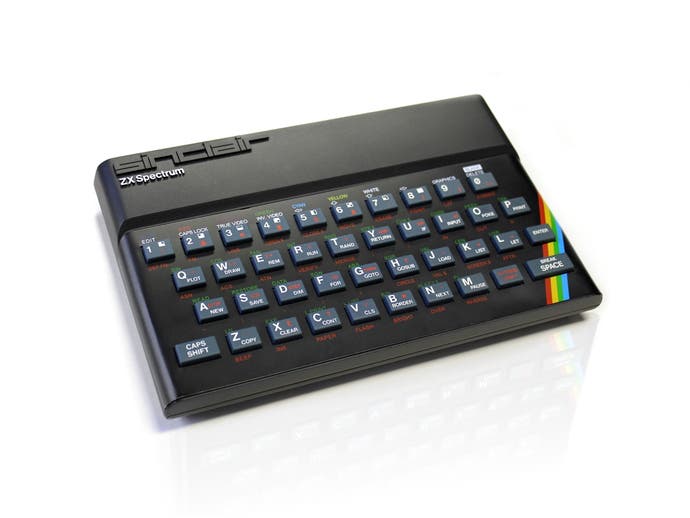

The ZX Spectrum was the follow-up to the ZX81 and helped establish personal computers in the home. The 'Spectrum' referred to the machine's colour display, and was matched by a stylised rainbow on the casing. Today it is still a bit of a shock to see just how small the thing is. Speaking with Eurogamer's Spectrum fanboy Ian Higton this morning, he suggested that, more than any other home computer, the Spectrum is loveable.

"I look back at the Spectrum years with great fondness," Higton told me. "Even though I was a bit too young to experience it right from the start, I still had many years of fun with my +3. The fact that games were so basic (no pun intended) meant that I had to use my imagination to fill in a lot of the gaps, but that made my time with them feel so much more personal. Games like Dizzy or Skool Daze or Chaos were like cartoons and comic books come to life, and I have wonderful memories of crowding around the keyboard, playing these games with my family and friends.

"There's such a strong pang of nostalgia surrounding my love of the Spectrum. Its games provided such amazing, mind-expanding moments for young me, but the memories are always mixed with a trace of sadness as they're times that will never be repeated."

Central to the Spectrum's success was its price, of course, with the 16k version coming in at £125 while the BBC Micro's cheapest model was £299. In a joint interview with the Spectrum's engineer Richard Altwasser, to mark the machine's 30th birthday in 2012, Dickinson told the BBC that "literally every penny was driven out where possible. So one of the consequences was that we would very rarely take an existing technology... but instead would engineer another way of doing it."

The classic example of this kind of thinking was the Spectrum's rubber keyboard, which replaced the hundreds of components of a conventional keyboard with a design using "maybe four or five moving parts." The ZX80 had used a membrane keyboard back in 1980, which is at least part of the same lineage, but the Spectrum's chiclet keyboard still stands out, because in its very rubberiness - it has famously been likened to "dead flesh", a judgement Dickinson often took a perverse pleasure in - it makes itself unignorable, a design statement as much as a mere solution. It is a wonderfully weird icon in its own right and reinforces the notion that a Dickinson design would always have character.

In the following years, Dickinson created industrial designs for early laptop computers. In the late 1980s he worked on the MacArthur field microscope and designed the portable Lensman microscope, which won BBC design awards amongst others. He contributed concepts and models for the first "Broad Band phone" for AT&T, and returned to games by designing the infamous Gizmondo console - it wasn't infamous for its industrial design, at least - and, more recently, the ZX Spectrum Next.

Dickinson was diagnosed with cancer in 2015. Following successful treatment, the disease returned last year and Dickinson died in Texas, where he was receiving further treatment, on the 24th of April. He is survived by his wife Elizabeth and two daughters.

His finest work,"born out of staggering innovation and clever shortcuts," as Dickinson put it in 2012, led to gigantic dividends. "Clearly we've spawned a generation which is now quite mature and has produced software for the many products that surround us," he said, with obvious pride.