Rime and reason: beneath the meaning of Tequila Work's artful wonder

How a brush with death informed a modern classic.

Warning: this article assumes you have finished Rime. If you haven't, you should! It's only at the end you understand something very important about the game, which makes it very special - Rime is much more than the serene Mediterranean adventure it seems. If that sounds like a spoiler to you, look away, but please come back again when you're ready for more.

On a porch warmed by the Mediterranean sun, Raúl Rubio Munárriz, creative director of Rime, tells me the moment which changed his life forever. "It's pretty stupid," he says. "One day I nearly drowned."

He was dating a girl who wanted to swim off the coast of Spain and, eager to impress her, he agreed. And so they started swimming, and swimming and swimming, into the sea. Soon they were one kilometre out, but Rubio was out of his depth. "We are very far," he called above the water, his body getting tired. "We should go back." But the girl was unfazed. "Oh come on," she answered. "Let's reach that buoy and then go back."

Rubio hatched a plan. He would cling to the buoy and rest like people in movies did. "But it's not like in the movies," he tells me. "It's slippery. I couldn't grab the buoy and I started to panic." He told her he was tired, and that he couldn't get back on his own. To which she replied, "OK," turned around, and swam off. "I was alone."

"'OK OK stay calm stay calm,'" he told himself, "but I couldn't, and I had a panic attack." Frantically he made for the shore, adrenaline overworking him, and a minute later he was exhausted. "I started to go down," he says, "to drown."

When he started swallowing water he accepted his fate. 'This is a very stupid way to die,' he thought, jocularly. 'Good luck taking my car out of the garage - you don't know where the keys are and it's a very tight spot.' But then something else came to mind which stung: the thought of his parents receiving news of their loss. 'My stupidity is going to cause them suffering,' he thought. 'I know my mother is going to suffer, my father is going to suffer, my brother is going to suffer.' He wanted to tell them it was OK, don't worry, but he couldn't. This is going to have a chain reaction and affect the rest of their lives, he thought. 'It shouldn't be this way. This is unfair.'

But as he sunk below the water someone spotted his arms above, and swam out to pull him back to the surface and beach. It was the brother of the girl Rubio was on a date with, the girl Rubio would later marry - who would later explain she thought he was joking when he said he couldn't swim back in. "I was lucky."

But Rubio was also mortified. His being "a fat potato", he smiles, and a weak swimmer had caused him to nearly die. "For a long time I was very embarrassed and tried to forget this moment. I wouldn't mention it to anyone," he says - so he repressed it, buried the trauma deep. "I didn't tell my mother until seven years later."

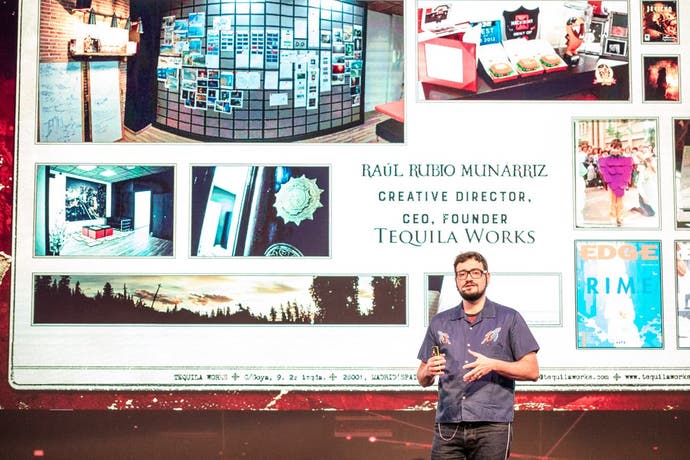

Raúl Rubio Munárriz is the founder, creative director and CEO of Spanish studio Tequila Works, which is nearly a decade old now, and which broke onto the scene with side-scrolling end-of-the-world horror game Deadlight in 2012. This was followed five years later - after a long and turbulent development - by Rime. But it wasn't always the Rime we know now. Once upon a time it was Echoes of Siren, a Microsoft game, a "Gauntlet meets Minecraft meets Jason and the Argonauts" adventure, according to the leaked game pitch. You weren't a fragile boy but a muscular Kratos of a man on a Robinson Crusoe-like adventure, gathering and crafting by day, and defending shelter from evil spirits at night. But Microsoft's plans changed and Xbox dumped Echoes of Siren, and Tequila Works was forced to look again at what it had - and it didn't like it. "What we were doing was not beautiful and crazy enough," Rubio says.

It was then, in the soul-searching, back-to-the-drawing-board period after, Rubio's repressed memory of drowning bubbled back up. During a conversation with writer Rob Yescombe it all came tumbling out - Rubio even discovered regrets he hadn't realised he'd felt before, namely his having missed out on having a child. And from the pool of grief and fear and guilt came the spark and meaning Tequila Works had been looking for.

Rime is the story of a father moving through the five stages of grief, slowly accepting the loss of his son, who was swept overboard during a storm and drowned. It's a heartbreaking revelation saved for the game's end, and it shines new meaning and understanding on all that came before. It's a moment which naturally provokes an eruption of questions from within, and there are myriad theories and discussions online about this. They are the kind of questions I didn't have when I met Raúl Rubio Munárriz last year, shortly after Rime's release - but this time I do.

"Oh, so you finished it!" he says when I tell him, face lighting up. And with scarcely an invitation he's away, into a long and winding explanation of the meanings of Rime I can only assume he's wanted to get off his chest for some time.

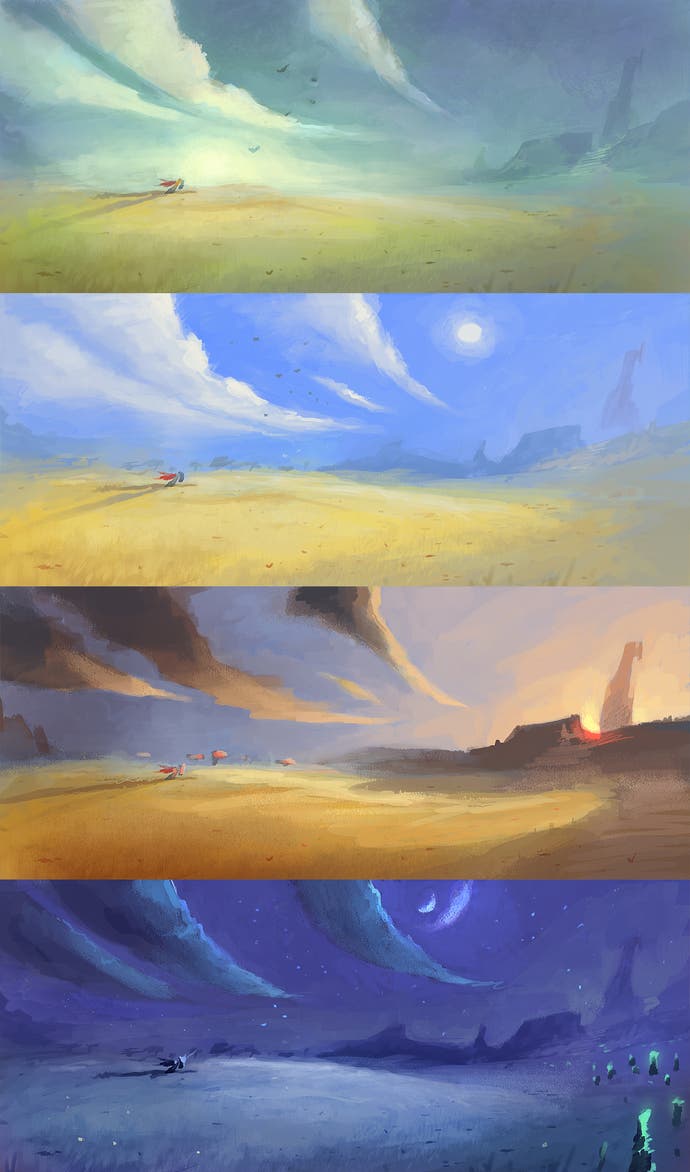

Rime begins in Denial, although you are a million miles from understanding it at the time. You wash up on the shore of a beautiful Mediterranean island, unsure of who you are and where. "It's like childhood in life," says Rubio. You are unaware and carefree, with no urgency or purpose bossing your way. "You can play all you want," he says, mess with the pigs, climb and explore. Everything's fine, everything's OK. It's a feeling of childhood echoed in the game's manipulation of light and perspective. "Child logic," he explains. "You really believe you can grab the sun and move it around - why not?" Sooner or later, though, you will be drawn to the thing you cannot ignore, the big white structure dominating the island. "The tower is always there."

Activating the tower, though, can be looked at another way. The child, you see, is the trespasser in the world. This fantasy is the father's way of cradling the existence of his child in a kind of limbo, where he suspends disbelief, keeping the merciless truth of reality at bay. It's the child who begins to disturb that peace and awaken things repressed and locked away. "For the father it was easier to accept this was not happening," says Rubio. "Everything was happy like Disney World, but when you woke up the tower when you moved the sun, the island was not pleased."

So after the boy climbs the tower for the first time - and ventures down the hallway through the giant keyhole of beaming light - the world changes for the first time, and Denial gives way to Anger. Which seems obvious - there's a giant angry bird who steals a large golden ball you need to solve a puzzle. A scenario inspired by football games as a child, Rubio tells me - and the moment you hoof your ball into a cantankerous old neighbour's garden. "May I have my ball back?" you ask. "No! It's mine!" they snap. Suddenly the world is hot, not pleasantly like before but baking, cracked and scorched, and it's during this phase the father, the island, begins to lash out.

"For the father - we call him Manu - is remembering, and his first reaction is 'I need to blame someone', because it cannot be his fault." This is why there are three windmills: one underwater; one made of wood and sails; and one painted with images of the boy. They represent what the father is trying to blame his loss on. "At first maybe you are blaming the sea, because the sea took away your kid. Then maybe you blame the boat because it was your way of life - why couldn't you be a carpenter? This wouldn't have happened! Then obviously you blame your own kid - he was careless, he shouldn't have done that, you were warning him."

The windmills are destroyed by the storms - the anger - unleashed there, and when they are gone there's no one left for the father to blame but himself. This is why the bird flies away in terror and why the shades appear, Rubio tells me, because they are what the boy is, only he doesn't know it yet - only the father won't accept it yet. It's why they cower from the boy. "They are afraid of you because you are so different to them," he says. "You shouldn't be like that."

Lightning strikes the bird's nest and, aflame, it chases the boy but falls and dies. In his anger, the father has killed it. He has also unknowingly destroyed the eggs in the nest. "That's Anger itself," says Rubio. It is blind and reckless.

This time when the boy scales the tower he finds himself back where he started, at the bottom, but not in a world lush like before, rather a swamp "full of crap" like you find behind the sofa. Like the father. This is Bargaining, where you seek help from a higher power - from the sentinel you create, the "webcam with legs", as Rubio calls it - to return things to the way they were.

Now the shades are aggressive towards you, or perhaps they are trying to get you to accept your nature as a shade. "Or maybe these shades are repressed memories, your bad feelings about sadness and shame," says Rubio, "and that's why they look like shadows because you tend to ignore and hide those feelings, and when they are exposed, maybe they want to look like the kid, take back their mojo."

While Bargaining unfolds, this fox and sentinel you brought to life begin to become close and start leaving you out, which is entirely intentional. "You think you're getting into something but you know what? You're not important, it doesn't matter," says Rubio. This feeling culminates at the end of Bargaining when the sentinels are awoken and simply walk off without so much as a nod in your direction. "You are just a guest," and your self worth is now on trial as you climb the tower for the third time to find it flooded with the father's oncoming Depression.

How to visualise Depression came to Rubio in a dream. "I fathered a child at this point and I couldn't sleep for two years. One of the nights I couldn't sleep I had this weird dream where I was alone in the world and there was only rain, and the rain was tears and I couldn't see anything. Everything was invisible," he says. "I couldn't see the world around me because I was so deep within my own depression."

It's this reduced visibility in the game which masks the fox running off and the sentinels sacrificing themselves to open doors for you. It is as in life: "Most people when they are depressed don't notice the people who are helping - they feel they are being taken advantage and no one understands them - and that's sad, because these people are the ones who are really caring for you but of course you can't see it," he says. "Sometimes your best friends need to sacrifice so you can move forward."

Try as you might you cannot stop the final sentinel, the one you first created, sacrificing itself on the final door. And scream as you might, you cannot prevent the fox, who you later hold in your arms, from fading away. "Many people told me 'You're a bastard! You killed the fox,'" says Rubio. "No! You created the fox, Nana, and the fox has fulfilled her duty to you. Her only purpose in life was giving you hope to accept your nature, and the nature of the kid - a shade." It's why the shades now ignore you, because finally you are one of them, there are the bottom of the father's mind, never to move forwards.

But depression - long and hard though it may seem - does not last forever, and so when you reach the centre of the Necropolis you break your chains and once again life rushes back into the world of Rime. "You are a shade but you are what we called Enlightened Kid - unlike the other shades. 'You know what? I'm not fading away - I'm going to stay. You need to accept me, I'm part of you.'"

It's then the world turns upside down and you realise you were on top of the tower and everything has been happening underwater, and so in order to get to the top you now descend, and when you do, you leap. It's a moment some people misinterpreted. "Oh so you need to kill yourself," they said. "No!" Rubio says. "The tower is inverted. The bottom is in fact the sky, the stars, so you are jumping into the sky, you are going to these stars, because you trust in it. You literally go beyond."

It is then, with nothing left to support the fantasy, Rime reveals the truth. "You have been noticing this mysterious cloaked figure in the game, and you know he was on the boat, but you realise it's you, literally you." The father - and now you take direct control of him. You unlock the door to your son's room and look around at the mementos maybe you collected in the game, and the cuddly fox, the representation of the mother in the game, Hope - with the father, the hooded figure, being Guilt, and the boy Loss. You turn to leave but suddenly see an apparition of the boy on the bed and you rush to him, embracing him, until finally, as he fades away, and as you dangle a remaining bit of cloth from the memory out the window in the breeze, you accept his passing and let go, sending it floating into the new dawn.

These are meanings as Raúl Rubio Munárriz sees them, condensed from topics he could easily speak hours on, for he is very quick to veer off on a deep and poetic tangent. But other people's interpretations of the endings vary. One person, for instance, believed Rime to be the Peter Pan tale of a man unable to accept his childhood had gone, while others flipped the meaning to be about hope and not loss. "The message for me is no matter what, the last thing you lose is hope, and even then you will, one way or another, reach the end, so it's OK," they said.

"We received lots and lots of letters ... very personal letters," says Rubio. People opened up about children they'd lost or loved ones they were about to lose. They were even, in some cases, the ones about to die. Some sought answers about the game, others sought answers about the afterlife. Others, meanwhile, thanked Rubio and team for helping them recognise their grief and the shape of the journey ahead. "Those were the best ones." And a few felt nothing, which was strange, but then, "Your life experiences are essential to make the game work."

How do you follow a game like Rime? It is a painstakingly made adventure of beauty and poingnance which nearly broke Tequila Works, and hasn't been terribly successful in return. Even the second-chance Switch release, a commissioned port, went wrong and caused Tequila Works more work in the end. "Last year, whew!" says Rubio. "It never ends.

"We know how to make a sequel to Rime," he adds, "but it wouldn't literally be Rime 2 - more like a spiritual successor to Rime. But are we going to make it? I don't know. Maybe one day we can come back but for now it's too soon - anyone who has finished Rime, maybe they'll understand why. For us it was a very very big journey and it was very intense."

But Tequila Works is working on new games, with the 60-person studio loosely divided into three 20-person teams. "We have several projects," he says. "The other teams are working on new stuff that we started last year but it's too soon to announce anything."

Nevertheless, he says one will be a virtual reality game. "After The Invisible Hours [a murder mystery I reviewed] we feel very comfortable with VR. If the focus with Invisible Hours was immersion - feeling like you are inside a story - in this case it's more about disruption, in the sense presence is key. I can be inside the story but do I feel like I'm disrupting the story? That's what we're exploring."

The other 'obsession' the studio is exploring - Rubio likes talking about in obsessions - is sandbox narrative in smaller, fairytale-sized stories. What happens if you make dialogue more like gameplay in a sandbox game, and allow emergent, spontaneous things to occur? It's something Rubio does every night conjuring stories for his child.

"For me it's like the story is a matrix where you have characters and locations and events so whatever my son changes is going to cause a chain reaction," he says. "We're [Tequila Works is] not trying to tell this epic saga or anything - in fairytales it's easy because there are very few characters and locations and events. That's what I do every night with my kid! And that's what we are experimenting with now."

It's here I leave Raúl Rubio Munárriz, on the sunny Mediterranean porch overlooking Croatia's Adriatic Sea. It's not quite the Mediterranean where Raúl Rubio Munárriz nearly drowned, but it's not a million miles away. And as I leave him, his real life is once again seeping into his work, albeit from a much less dramatic place than with Rime. I am encouraged. How can I not be? Look how well it turned out last time.