The rulebook for a million summers

A return to The Spy's Guidebook.

I bought my daughter a magic colouring book last week. It is amazing. You open the book and it's just black-and-white pictures of fairies and flowers, the lines of the illustrations heavy and rather sooty, as if they've been copied from some ancient fairy and flower 'zine. Anyway, it's all black-and-white, and then you run a paintbrush loaded with water over the pictures and - shazam! - they're suddenly coloured in. The right colours, too: a fairy tunic will be green while their stockings will be pink or purple. A tree will have a brown trunk, a mushroom will have a bright red cap.

"How does it work?" my daughter asked me. Within a year, I reckon, she will know not to ask me this anymore - I never know the answer. Regardless, she had to ask because she had simply never seen anything like this magic colouring book. I had never seen anything like it! And then I realised that - in a way at least - maybe I had.

Do not misunderstand me, I am still dazzled by books with alarming regularity. Every few weeks something will come along and make me feel like it's the first book I've ever picked up - the first and the most urgent. Just yesterday, I finished Christopher Fowler's The Book of Forgotten Authors - Essential, I reckon; it's a banger - and through it I've been thrown into the worlds of Lord Dunsany and - whisper it - Ernst Wilhelm Julius Bornemann. But I'm going to talk about a different level of enrapturement here - what you might like to call the magic colouring book level. An encounter with the kind of book that seems so perfect you suspect it is made for you alone, and so engrossing it is not so much a book anymore but an entire world, so engrossing that you feel inside its covers there is an entire new way of living to be found.

This sounds over the top, but I'm talking about the books you encounter between the ages of five - my daughter was five this week - and, say, eight. The kind of books that are entirely formative. The kind of books - crucially, since this is Eurogamer - that often feel game-like in the ways that they encourage you to try interesting things and to see your own landscape a little differently after you've finished with them. And for me, it wasn't magic paintbrushes and gloriously sooty pictures of the tangled weed-world of fairies. It was secret agents and uncrackable codes and tricks stored in matchboxes. It was The Spy's Guidebook.

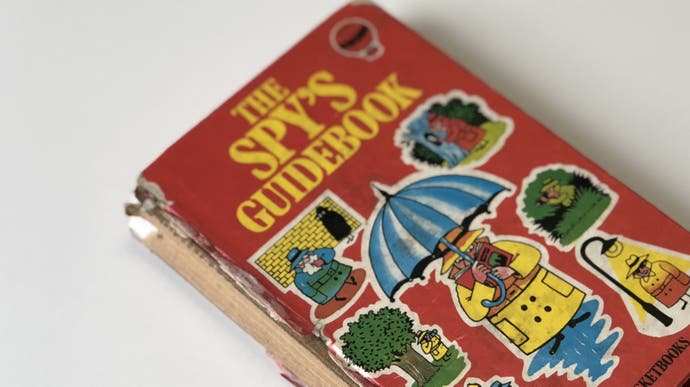

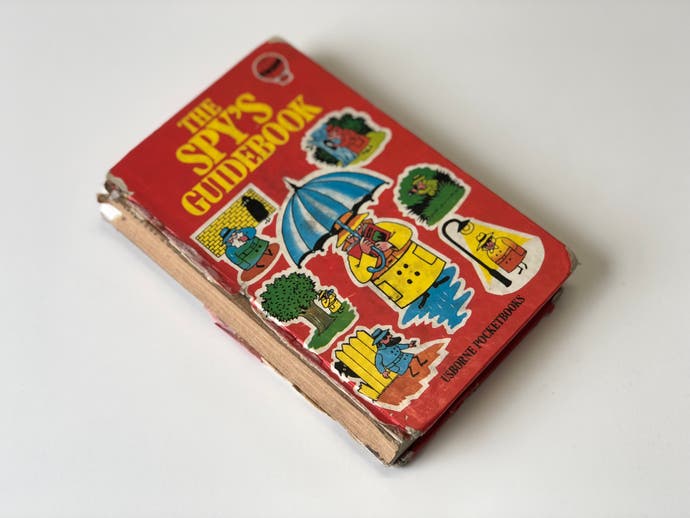

The Spy's Guidebook was published by Usborne, the brilliant kids' publisher whose icon back in the day was a little hot air balloon. They earned that balloon, too, because oh, man, their books took me places. I think the various contents of The Spy's Guidebook was published in separate volumes at one point. I definitely remember having a smaller book that just detailed secret codes and all that jazz, but then my sister and I found out about a bigger book that offered every single thing a spy would need to know. I remember ordering it from a bookshop, and then one day it arrived: glossy red, hardback, thick white pages, gadgets and subterfuges galore.

Usborne made a detective book too, but detectives seemed a bit square and law-abiding. There was something about the illicit world of the spy that appealed to a seven-year-old, and appeals still, I think. The sense my sister and I had at the time, although neither of us would have found these words, was that summer itself - the long summer holiday between school years - might be one big game, and this book might be the rules.

This is how I remember it, anyway: long empty summer weeks with this book to keep us company. Learning codes, writing messages, leaving them in drops, making plans and generally keeping a close eye on anyone suspicious, which meant our neighbors, basically. Our world was small back then - we lived on the edge of Canterbury with no real access to the countryside and no nearby parks. Besides, this was the 80s, the era of constant safety adverts about stranger danger and electricity pylons that were just waiting for you to throw your Frisbee into their open metal arms so they had a reason to zap you and set your head on fire, so we lived in a constant state of terror that kept us close to home. We were suburban spies, I guess: shuffling Smileys in premature retirement somewhere. Anything too bucolic in the Spy's Guidebook was useless to us. We were all about chalk signals on brickwork, about tailing people as they went to the corner shop.

This is how I remember it, anyway. But my memory is terribly fuzzy. There doesn't seem to be much at the centre of it. I have a sort of lazy summer espionage milieu, but I am missing anything in the way of plot points.

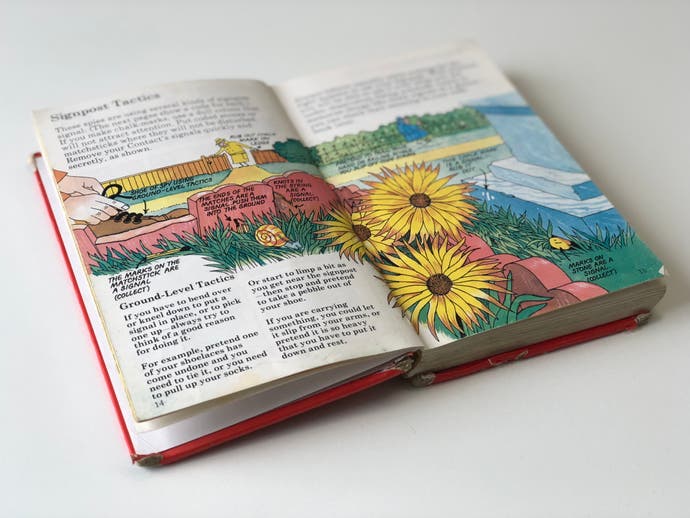

Happily, I found my copy of The Spy's Guidebook recently while clearing out my mum's old house ahead of a move. I've bought fresh copies over the years in bursts of nostalgic melancholia, but I never managed to get the red hardback again. For a while, it was printed with a spiral binding - a type of binding that I particularly hate - and then there's the paperback, which doesn't have the same tome-like heft that a book that this demands.

My original copy, though, freshly rediscovered, is still a cracker. The gloss has faded to a kind of mottled, dusty matte, and the spine is long gone, the bare cardboard on the inner binding exposed. But all the pages are intact, as are the blank end-papers in which I once wrote my name in a handwriting I no longer recognise.

And opening this copy a few weeks back I was eager to know: what's in this book? What is being a spy actually all about? What did we do with it back then?

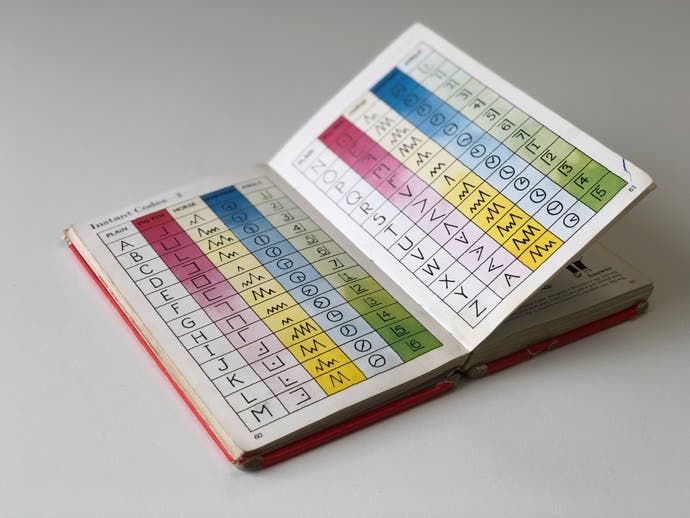

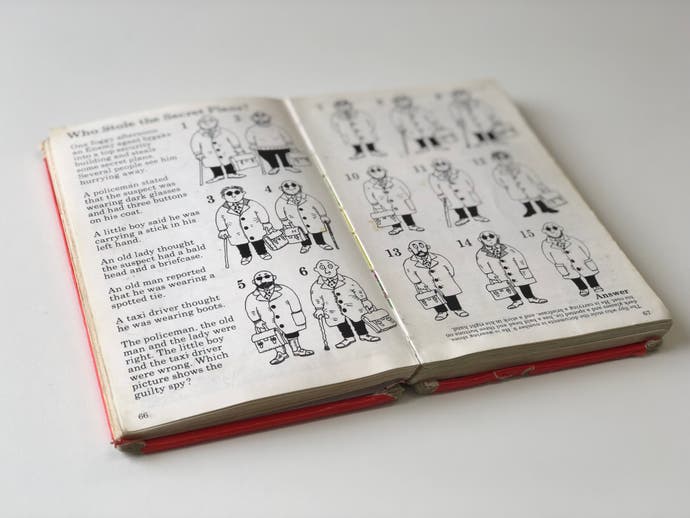

And, well, codes - pages of them. Morse, Semaphore, Angle and something called Pig-Pen that I still have very warm feelings towards. And there are signpost messages - matchsticks you can mark up, painted rocks that might warn a fellow agent of trouble ahead, loops of string you might knot in a certain way. There is some unconvincing stuff about disguises, and there is a lot about tracking different kind of footprints, and there are also games and activities - variations on the sorts of things you might get up to outdoors as a scout, but also pictures to look at and study to spot suspicious characters and that sort of thing.

But the games were never the real appeal. They felt childish to us, back then, two primary school spies who were determined to pass messages to each other, even if we didn't really have much of note to communicate. Reading the book now, I wonder whether some of the stuff in it might have been thrillingly drawn from real early 20th century tradecraft - the codes, the drops, the newspapers which have had their pages quietly reorganised with a pin. The book is certainly written by people with a certain kind of grown-up name: Ruth Thomson, Heather Amery. Christopher Rawson sounds like someone who might have gotten a tap on the shoulder at Cambridge, and Falcon Travis, first listed amongst authors and hence the spy ring leader, I presume, sounds like they were the man or woman who probably gave Rawson the tap in the first place. It's this sense, of a children's book written by adults who were writing just before the great professionalisation - and tidying up - of children's books in general that gives the book its strange allure. It is a weird artefact of childhood, but also an artefact of the act of communication across the child-adult divide. I am not explaining this very well, I know, but my sense of this strange liminal state of the book remains very strong. Intoxicating.

In truth, having read the book cover-to-cover over the last few days - well aware that we never read anything cover-to-cover as kids, dipping in and out on arcane whims - I'm still not sure what we actually got up to with it. We learned the codes and we packed those matchboxes with little gadgets a spy might need, but then we were left, seven-year-olds or so, in a world in which we were not spies and did not, actually, have a great deal of important things to do. The appeal of the thing, I suspect, was that it was this book we had that hinted at great adventures. Our spying took place in our heads, I reckon. In our heads we wore the brightly coloured raincoats and matching hats and sunglasses that the spies wore in the illustrations. In our heads we were prone to falling into mysterious plots that required lots of tailings and message sendings and dead-drop watching. In our heads we were allowed to stay out late and act mysteriously under the moonlight.

This is where the book's richness lies, I think. In its sense of untapped utility, in the sense that it is the preparation for something that will actually only happen in our imagination. And in truth The Spy's Guidebook is not actually alone in this regard. Every now and then I find another book like it and I cling to it, just like my daughter has not really let go of the magic colouring book since she got it. Every now and then I find another book that seems to require something more from the reader than other books do.

Judith Schalansky's Atlas of Remote Islands is such a book: beautiful prints of tiny islands scattered over the globe - islands that the author knows she will never visit, but has recreated first as pieces of precise cartography and then as short chunks of text. It is an unblinking sort of book - it will not look away.

I learned of this book from the people at Simogo Games, and so it is inevitably tangled up with Year Walk and Device 6 - games, but also pieces of text and audio and imagery, objects that are there to be explored and examined as much as merely played and completed. Games to prod and shake and hold to your ear like a strange conch.

I see a little of it in my recent crush on cook books - it started years back with Shopsin's glorious Eat Me, which is a memoir and a guide to a certain way of life as much as it is the book I turn to for the chilli recipe that I have made at least once a month for the last five years. It has spread to Christina Tosi's Milk Bar book - cut the salt in half if you're making cereal milk panna cotta, gang! - which is again a book to read and re-read and think about as much as it is a collection of recipes to see you busting out the KitchenAid.

For these things, the normal words, I would argue, will not do. They are not books, not games, not collections of favourite dishes with instructions on how to make them. They are transportative objects, chunks of pure writability. And somewhere, surely, there is a paintbrush loaded with water, or just the right size of matchbox ready to be transformed into a toolkit, to bring out all that is truly inside.

Thanks to Paul Watson for the lovely photographs.