Shenmue and the blissful boredom of being young

Notes from a first-time player.

I remember my teens, my early twenties. I'm not talking about the febrile highs or the painful embarrassments - although I remember those too - but the sheer aimlessness, the great stretches of unoccupied time, the loafing. Waiting for the one daily bus into town from the Northamptonshire village where I grew up and killing time window-shopping until the one bus back; later, as a procrastinating student, ambling down Coney Street in York, pastry in hand, knowing my afternoon would end in me clocking the Super Mario 64 demo for the umpteenth time in GAME, as if I didn't have anything better to do. Maybe I didn't.

There's anxiety and depression at that age, a crippling fear that you will never find out who it is you are supposed to be and what it is you are supposed to be doing. But hand-in-hand with that suppressed turmoil goes a blissful boredom, a vacant, nothingy existence that might be enforced by a lack of money or purpose, but that has its own remorseless momentum. It won't let you go and the clock won't move any quicker to the time you want it to be - the time when something will happen. We like to romanticise youth as a frenetic blaze of glory, but for the young, dear God, life comes at you slow.

I remember it, but so different is my life now, it's hard to remember what it was really like. I did get a taste of it this past week, though, playing Shenmue for the first time.

Sega AM2's unfinished magnum opus is a total one-off - and not only for the right reasons. Conceived as a multi-part epic, it was over-ambitious, vastly expensive to make and a commercial failure. For better or worse, it also represents an artistic dead-end as a way to imagine the scope that major video game productions could aspire to. A couple of years after the first episode was released in 1999, modern video game bigness would be defined by Rockstar's Grand Theft Auto 3. But Shenmue's director Yu Suzuki had something altogether different in mind. Its status as a road not taken in game design makes Shenmue, for all its clunkiness - not all of which can be excused by its age - well worth experiencing today in its long-overdue reissue.

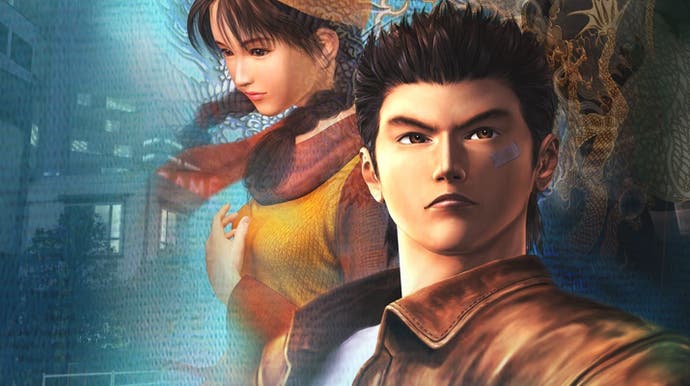

The story sounds a lot more conventional than the game is. It also sounds more B-movie than blockbuster, which may have been one of Shenmue's commercial challenges. Ryo Hazuki, 18, lives in a suburb of Yokosuka, an unremarkable Japanese port city, in 1986. His father runs a martial arts dojo and Ryo is a keen martial artist himself. One day, he witnesses his father's murder at the hands of a mysterious Chinese man and his henchmen. He swears revenge and sets about trying to discover who these men were and why they killed his father. (The police, oddly, are entirely absent from the hyper-realistic representation of local society.) His quest leads him into the criminal underworld and towards hints of something more supernatural and strange, but not to a final confrontation with his father's killer. That's something fans are still waiting for, 19 years later - and it's not even certain that next year's crowdfunded third episode will supply it.

What sets Shenmue apart is not this earnest potboiler plot but the world it takes place in, as well as the freedom you are given to fully inhabit that world - and the constraints placed on that freedom.

The word realism is often used to describe video games, usually their looks. But realism is very rarely an artistic goal of the games themselves. Even when setting games in the real world, most creators, certainly those working with big budgets in the mainstream, cannot resist the lure of fantasy. In Grand Theft Auto, Rockstar offers whole cities as limitless playgrounds for fantasies of power and liberation. They are big places that only accommodate big actions. What could be more real than the freedom to do whatever you want? Well, just about anything.

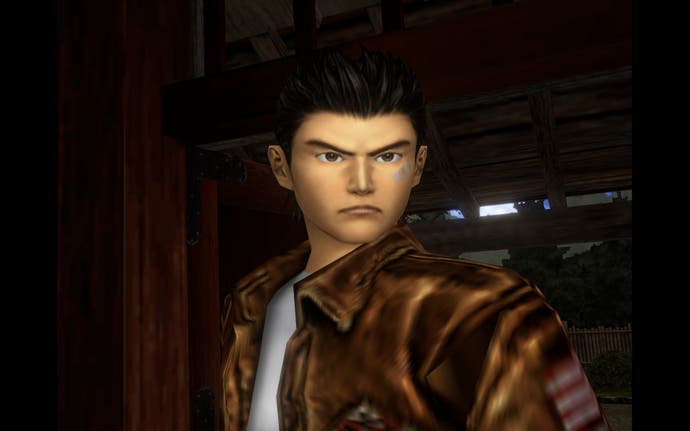

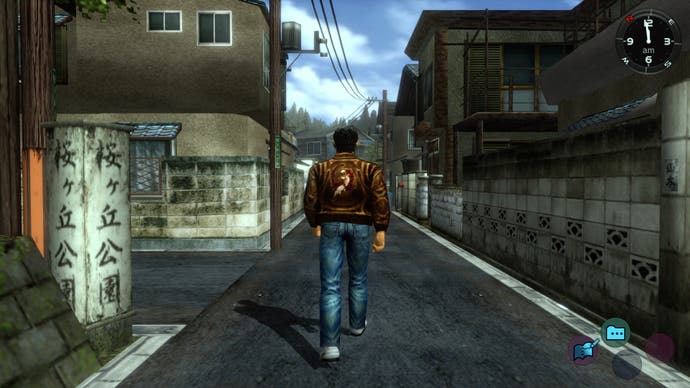

Shenmue, despite its genre plot, is a true realist game. Suzuki may have had an epic story to tell but he wasn't interested in a big canvas. He had his artists draw life in a dead-end suburb of a dead-end town in mid-80s Japan in meticulous detail, and squeeze it all into a handful of streets. They made sure that every single inhabitant of this place, even the milling strangers who would never have anything to say to you, had an individual and recognisable human face and voice. The programmers created a persistent clock, a day-to-night cycle with variable weather, and daily routines for the characters, beating Nintendo's haunting The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask to the punch. Nintendo, being Nintendo, used this idea to create intricate story-puzzles and added a time-loop mechanic to make them playable. AM2 used it to create a simulacrum of humdrum daily life - and to force the player to wait.

In the last two decades of advancing tech and ballooning budgets, the beauty and fine detail of Shenmue's art assets has naturally been outstripped. But it has never been matched for its real-world cultural specificity, from the particular look of the street signs and travel agents' flyers to the economic conditions affecting the workforce or the history and makeup of Yokosuka's Chinese immigrant population. There are nostalgic beats, of course - famously including fully playable Space Harrier and Hang-On cabinets in the local arcade - but the 80s setting isn't cynically exploited for retro set-dressing. The overall effect is powerfully evocative. A vividly remembered and intricately described reality can be as transporting as any fantasy.

Shenmue's great gamble, which won't pay off for all players, is to force you to live that reality. I don't think a major, mainstream video game studio has ever made a slower game. Its most conventionally exciting element, the martial arts combat, might also be its least consequential, despite being conspicuously well produced (it's based on Suzuki and AM2's Virtua Fighter games). For the first two-thirds of the game you rarely encounter fights, and by the time they become prominent toward the end, you have become so enmeshed in the rhythms of daily life that they feel more like interruptions than highlights.

Most of the time, Ryo plays detective, following clues and rumours, asking around, making notes in his notebook - and waiting, waiting, waiting. Often your next lead can't be followed for another 24 hours, but you can't speed up time. You can't even give up on the day and go to bed before eight o'clock in the evening. So you have to do something games almost never ask you to do: just exist.

Since you're not given a choice in the matter, Ryo drifts. He helps a small girl nurse an injured kitten back to health. He goes to the arcade. He avoids talking to a young woman, Nozomi, who has a crush on him. He wastes money on capsule toys, cassettes and raffle tickets. He stands on street corners drinking cans of Coke. Everybody in the area seems to know him; he is friendly but aloof, keeping a polite distance. His quietly emotional housekeeper, Ine-san, makes awkward scenes.

Eventually, because the plot requires it, he gets a job down in the harbour driving a forklift truck. Astonishingly, the game then requires you to turn up to work and do a shift every day, moving stacks of crates from one location to another, back and forth, back and forth (albeit enlivened with a silly warm-up race every morning). It's metronomically tedious, but it also comes as a strange relief just to have a task to accomplish at all.

Shenmue is often compared to Sega's later series Yakuza, which shares its obsessively detailed real-life urban locations and its wealth of mini-game frippery. Yakuza can certainly be seen as an attempt (a successful one) by others at Sega to turn Suzuki's idea into something marketable. But with its strutting gangster leads, Yakuza has a whiff of glamour that Shenmue sternly rejects, and it never has the courage - or the stupidity - to force you to take the downtime. If any game can be thought a kindred spirit, it's surely Atlus' role-playing series Persona, in which teen protagonists have to balance the pressures of schoolwork and socialising with a double life as occult dungeon-crawlers. Though far less literal than Shenmue, Persona too designs real life around its outré adventure and asks you to play that real life just as seriously, if not more.

Shenmue's animation is stiff, its story beats are cheesy and its acting is wooden. Some of the meaningless diversions are played for novelty, so they haven't aged well, and sometimes the whole enterprise just collapses into hapless camp. Yet in the hypnotic repetition and empty stretches of time created by its unwavering commitment to the clock, Shenmue describes a convincing emotional landscape for a lost teenager. It's numbing, claustrophobic, fundamentally very boring, but also luxuriously self-involved: a heightened state in which a twilit walk down an empty backstreet, just because you have nowhere better to be, can be too beautiful to bear.