Fallout 76 is an entertaining compromise

Three hours in post-apocalyptic West Virginia.

In John Hersey's novelistic account of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the nuclear blast at once divides and unifies. It's the synchronising point for six parallel lives - six total strangers joined forever at 8.15am, 6th August, 1945. The idea of the nuclear blast as a kind of photographer's flash, framing and composing its victims in a single, baleful instant of universal transformation, has since become a staple of post-nuclear fiction. 73 years later, the Bomb again performs a synchronising function in Bethesda's Fallout 76, but to rather different effect. It exists here as a weekly public "endgame" event, triggered by gathering widely dispersed launch codes and assailing a control room, its arrival time and explosive radius marked on the map screen for all to see.

It's with this that Bethesda concludes our three hour demo, inviting journalists to witness the calamity from the hillside around Vault 76, the game's starting area and character creation hub. The countdown ends just as I fast-travel in, breaking off my solo investigation of a museum rumoured to contain traces of the Mothman, an old West Virginian legend. I don't even see the missile land. The air turns white, then crimson as the frame rate plummets. We shuffle in the glow, a gaggle of level 6 scavengers in mismatched leathers and party hats, watching the fireball rise out of the valley below. Then, like the fools of history we are, we tumble down the ravaged slope together, yelling and firing our guns as purple clouds hiss upward to meet us. Our bodies buckle and deform, like the flesh of cartoon characters: switching to my Pipboy menu, I find that my skin has become bioelectrical, with a chance of shocking anybody who touches me.

Soon, however, the rads overwhelm my health bar and I collapse between newly irradiated trunks. The holocaust will linger for a few hours, twisting the location's fauna and flora into extra-hazardous shapes. It will somehow spawn rare items and crafting recipes, a fierce temptation for any player with the armour, meds and determination to weather the horrors within. Then it will fade away, leaving the area much as before - until next week, at least, when another set of launch codes are spawned. Fallout has always taken great relish in such devastation, from its elegiac announcement trailers to Fallout 3's infamous Megaton quest, but this is the first time a Fallout game has turned the apocalypse into a question of routine, a thing to gather around and re-enact, again and again.

It's a peculiar, deflating way to think about weapons that may yet kill the world, and that weirdness applies to much of Fallout 76 - a lonesome post-American epic that also wants to be a 24-player always-online shooter with PvP, four-player squads and a loot-centric endgame. Each side of the game has its moments, and the online requirement notwithstanding, the multiplayer elements aren't forced on you. Thanks to the map's sheer size - four times that of 2015's Fallout 4 - some odd but workable anti-griefing systems and the option to switch PvP off entirely, it's possible to play this much as you would a traditional Bethesda RPG. Even when exploring as a group you can always pursue separate paths, fast-travelling to one another's position should a player discover something especially intriguing (or dangerous). All the same, Fallout 76 feels more like a forgiveable compromise than anything else, a meeting of genres that entertains but, much like those weekly mushroom clouds, doesn't quite leave a mark.

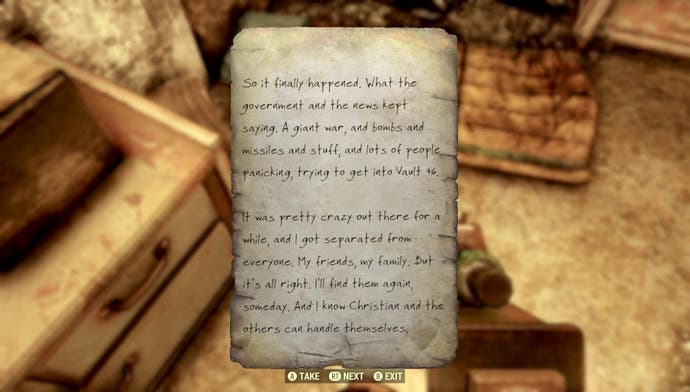

The game is set in 2076, some decades before the other games in the series, and 300 years after the founding of the United States (the anniversary theme is provocative given the current discourse around patriotism in North America, but only time will tell whether it's more than set dressing). As ever, it casts you as one of the last surviving humans following a nuclear armageddon, setting out from your fallout bunker into a wasteland full of things to shoot, collect and equip. Your initial goal is to track down your vault's Overseer, who has left a trail of audio diaries for you to follow, but on stepping through the cycling door, you're free to stroll off in any direction, level up and untangle the game's web of embedded narratives as you see fit.

The moment-to-moment is identical to Fallout 4, with the same FPS control scheme, the same first-person base-building interface, and the same nagging yet seldom lethal approach to survivalism: there are hunger and thirst bars that deplete your maximum stamina, used for sprinting and melee combat, should they fall too low. The weapons and armour pieces that quickly fill your inventory are the classic Fallout blend of retro-futuristic and makeshift, from revolvers cobbled together from wire and pipe through elderly powered armour to boxy rayguns and Max Max-esque rawhide baldrics. Your wrist-mounted Pipboy terminal, meanwhile, allows you to view stats (including limb-specific injuries and the effects of drugs), peruse backstory artefacts such as holotapes and listen to radio transmissions. The game disables PvP till you reach level 5, so there's plenty of time to get to grips with all this and make inroads on a few quests before you have to worry about other players, and even then, you're free to switch it off again in the settings.

The topography displays all Bethesda's usual knack for guiding the player without appearing to, challenging you to stay focussed as each rise or curve of the road exposes another intriguing silhouette or pattern of colours in the undergrowth. Vast shapes along the horizon are a perpetual draw, but look here, is that a tumbledown barn you glimpsed through those trees, and what of that burned-out minibus straddling the cliff? Where Fallout 4 was a little too built-up for my tastes, the West Virginian countryside is pleasantly mysterious, with its enveloping forested hillsides, relative scarcity of town environments and abundance of eerie rural legends. There are grander structures, such as an in-game rendering of the Greenbrier, the colonial golf resort that conceals a real-life fallout bunker, but the intricacies are often more fascinating than the extravagances - gap-toothed billboards on misty hilltops, the hush of a clapboard church and the way sunlight fills in the crevices on a tarmac road.

You'll meet many a foe on your travels, including a number of familiar faces, from the burrowing molerats to laser-armed Protectron robots to the feral ghouls that populate battered residences. They fight much as in other games, scuttling crab-wise into cover or rushing your position. Level gaps make careless aggression unwise - as far as I can tell, there's no recommended level for quests, and no advance warning of what you'll find in each region - but you can often get the better of tougher foes by kiting them around or luring them into tight spots where the AI pathfinding struggles to keep up. Travelling in groups obviously helps: at one point, my greenhorn team managed to slaughter a sleeping level 30 mutant bear by mining the entrance to its warehouse den, then lobbing baseball grenades at it as though egging a politician. We had less luck putting down a flying dragon creature, which pummelled us from on high with radiation waves, sapping movement and the frame rate, while we pecked away at it defiantly with throwing knives and shotguns.

The toughest foes of all are inevitably other players, though the temptation to treat this as a player-killing game is checked firstly by the option to disable PvP, and secondly by a baroque set of anti-griefing systems that reveal the Bethesda Austin team's prior experience with the infamously lawless Ultima Online. There's no penalty for attacking another player providing they fight back, and the game courteously equalises level differences to ensure a fairer fight, though you'll still have to factor in quality of weapons or gear. Kill another player who doesn't resist, however, and you'll be tagged on the map screen as a murderer, which means that other players (including, in a devilish twist, your own team mates) can kill you to collect a bounty. Said bounty is stripped from your own cash reserves, and if you don't have the cash to spare, you'll incur a "debtor's debuff", lowering your damage for a few hours versus both other players and NPC enemies (this doesn't appear to stack). It's a pretty withering method of keeping the anti-social sorts in line - or, depending on your point of view, a way of raising the challenge for yourself at the expense of everybody else.

The biggest casualty of the game's always-online approach is Fallout's old turn-based VATS system, which is now obliged to function in real-time, and deals with this like somebody trying to fence with one hand while doing their algebra homework with the other. It's essentially a first-person lock-on with a chance-to-hit percentage, which rises and falls blindingly fast as each combatant moves about and terrain factors come into play. The system is handy when scouting for opponents in the long grass - you'll feather it on and off as though pinging a sonar - but as a combat aid it's messy and frustrating. I quickly dispensed with it, even after unlocking a perk card that lets you target specific limbs, as in previous games: this simply creates more fuss, as you cycle body parts frantically in search of the highest percentage.

There are more positive things to say about the redesigned character customisation system, which recalls the freeform loadout approach of Call of Duty: Black Ops. You'll gain XP and spend points on stats like Strength and Perception, as before, but these points also now unlock Perk Cards - abilities or traits corresponding to one of your stats. You can equip one per stat, shuffling them around at will, which allows you to tailor your tactics to the situation. If you're inclined to get in the way of bullets, you might pick a card that automatically uses a health item when you take a certain amount of damage. If you're minded to spend long spells foraging, you might equip one that raises your carrying capacity. The variety is pleasant, though none of the cards are all that eyebrow-raising in themselves. There are two rarities of perk cards, but the difference is cosmetic: rarer cards come with fancy animations and a gold finish, but have no additional impact on play.

I wasn't able to spend much time with the base-building, largely because I managed to lose most of my crafting resources after getting killed repeatedly by the aforesaid dragon - thankfully, weapons, gear and health items aren't lost when you cop it. As in Fallout 4, the building options range from foundation elements such as staircases and ceilings through decorative fixtures such as lamps to defences such as turrets. The key difference is that you're free to move your base as required - rather than looking for preset points, you drop a base camp unit (which also serves as a fast travel point) to create a building zone around it. The game won't let you build everywhere - you can't slap down your own creations atop painstakingly crafted quest-critical structures, and the building zone can't overlap with that of another player. In the event that a player joins your session who has set up camp in the same location, the game will dismantle their base and "blueprint" it for later restoration, though I wasn't able to see how this works in practice.

One unintended effect of building a camp is to make prominent the absence of friendly human NPCs in Fallout 76. There are no townsfolk to worry about, no settlers to recruit from distant parts of the map, though other players might drop in for a Nuka Cola or two or to exchange a few emotes. Quests, which generally boil down to going somewhere and collecting something, now hinge entirely on notes and audio diaries or at most a conversation with an eccentric robot. The game's lack of a citizen populace to woo, steal from or massacre has divided fans of the series; in practice, I found that it heightened my appreciation for Bethesda's ability to tell a story through the geography and the arranging of stray objects. The humans are gone but this remains a world etched and coloured by the lives once lived within it. There are still those tragic tableaus beloved of Skyrim and co, and they are still poignantly at odds with the gotta scrap 'em all mentality players are encouraged to adopt. Scaling an old colonial residence, I find two skeletons embracing each other near a pile of alphabet blocks. That these might spell out something profound only occurs to me after I've shovelled them into my inventory to serve as fodder for building projects.

Perhaps that's Fallout 76's real feat of the imagination, rather than its reduction of the almighty nuke to a cycling game-as-service mechanism. It tantalises with the thought of a loneliness as big as a county, a landscape of hollowed-out vignettes - Gone Home with the resources of an open world blockbuster at its disposal. But then a team-mate bounces a grenade off your head just as another group crests the road in a rattle of shotgun fire, and you're back playing that other game, the knockabout party blaster wearing Fallout's skin. It's not a natural marriage, but it has a certain rough-and-ready charm, and I'm curious to see where it takes us.

This article is based upon a press trip to Virginia. Bethesda covered travel and accommodation costs.