Traps, treasure and ancient tomb raiders

Press X to not die.

You're exploring the ruins of an ancient, forgotten tomb when you hear the sudden, tell-tale grind of a pressure plate underfoot. For a fraction of a second all is calm, but you know something's coming. The only question is what. Poison darts shot from hidden sconces in the wall? An unseen trapdoor opening over a pit of vicious spikes? A blade swinging down from overhead? Or that old beloved classic, the rolling boulder.

We take it for granted that gaming's ancient dungeons and tombs are filled with booby traps just as much as that the torches are still burning or that even though gangs of bandits might have holed up inside, all the treasure chests are mysteriously unlooted. (Treasure chests are weird in themselves; how often is treasure ever really found in chests?) Seemingly, no self-respecting tomb-builder of antiquity would construct anything without an elaborate set of hyper-efficient mechanisms that somehow still work thousands of years later. And then there are the traversal puzzles. Only slightly less a staple than the booby-trap is the idea that forgotten ruins include bottomless chasms or hard-to-reach doorways that you can only get past with a very particular athletic skill-set. Just imagine doing that while carrying a sarcophagus, or all those treasure chests that need to be hidden in the deeper parts of the tomb.

What might be surprising is how old this idea is. It stretches back to the ancient world itself. Perhaps nowhere is more associated with these kinds of pitfalls and traps than Egypt. Its pyramids were labyrinthine and genuinely filled with fabulous wealth, at least before only-slightly-less-ancient tomb robbers got to them. The Greek historian and collector of tall tales Herodotos tells a story of a fictional pharaoh Rhampsinitos, supposed to have reigned before Khufu, around 2000 years before Herodotos' own time.

He had a treasure-vault built to house his vast wealth in silver, but the builder added a secret entrance so that his sons could stealthily loot it. Finding his hoard diminishing even though the seals on the doors remained unbroken, the pharaoh had traps installed around the treasure. Another ancient Greek writer, the traveller Pausanias, has an almost identical story, but the location has shifted from early Egypt to the Greek sanctuary of Delphi, seat of the famous Oracle and a site where city-states from all over Greece would build treasuries to show off their wealth and prestige.

Probably the most tantalising and famous 'real-life' booby-trapped tomb is that of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang. His huge tomb at the foot of Mount Li is subject to many legends, only fuelled by amazing and outlandish discoveries like his Terracotta Army. Supposedly, the main tomb contains great replicas of his empire, complete with rivers of poisonous mercury and crossbows set to shoot intruders. For a number of reasons, the tomb has never been excavated, but there are indications of high levels of mercury vapour inside, which has further stoked the legend. Within games, Qin Shi Huang's tomb notably inspired Tomb Raider 2.

And what about the traversal puzzles? There are ancient precedents for these too. One of the lesser-known and more wonderful sets of legends from late antiquity and the early Middle Ages is the so-called Alexander Romance, a collection of unlikely tales surrounding Alexander the Great that built up in the centuries after his death and mingled Greek history with extremely multicultural myth and folklore. This article isn't meant to be about the Romance, but let me gush about it for just a minute. It really does have everything. Want Alexander fighting sea-monsters in an ancient submarine? It's got you covered. Alexander in a griffin-powered airship? No problem. A nice bit of proto-Tolkien with Alexander walling up the 'Unclean Nations' of Gog and Magog in a land surrounded by mountains and sealed off by a great black gate that will open at the end of time? All there.

For now, let's talk about the Pharos of Alexandria. This most famous lighthouse of antiquity and Wonder of the World accrued a lot of legends in the Romance, from moving statues to a giant mirror. Supposedly, there were labyrinthine caverns and vaults beneath it, which Alexander filled with his captured treasure. But these caves weren't easily navigated. An Islamic account tells of great ravines and a colossal chasm, at the bottom of which was the enormous glass crab upon which the Pharos' foundations rested (no, really). When king Ubayd Allah of the Maghreb invaded Egypt at the end of the first millennium AD, he managed to gain access to these tunnels and sent horsemen to explore them. You might question the wisdom of exploring dangerous and precipitous subterranean caverns on horseback, and you'd be right. Many of the riders are said to have plummeted to their deaths. That's why we get off our horses before we go into dungeons.

The legends are old, but was there any reality to any of this? Did anyone really booby-trap their treasure-vaults and tombs? It's hard to find any clear examples, at least while Qin Shi Huang's tomb remains unexplored. But tomb robbery was a big deal in the ancient world. Wealthy people were often buried with extravagant and expensive grave-goods, as everyone would know. There was a strong temptation, if you could avoid the guards (or if you were a guard) to break in and borrow a few things. It's very rare for archaeologists to find a wealthy burial that hasn't been picked over by looters long ago (nice of Ubisoft to build a large chunk of Assassin's Creed: Origins around this).

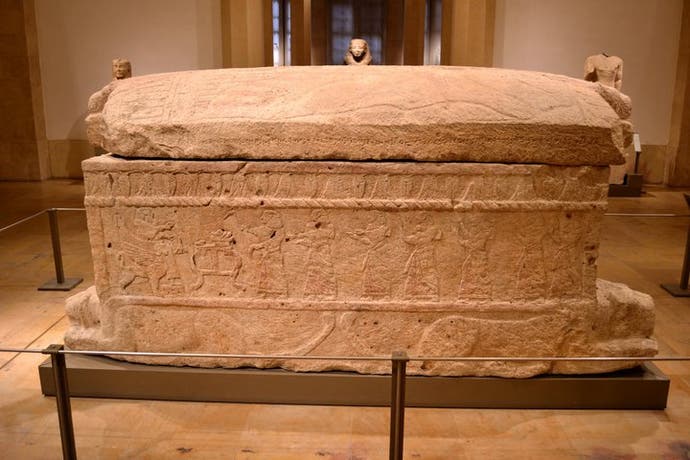

There was apparently a particularly bad spate of tomb-raiding in late Ramesside Egypt, recorded in documents from the 'trials' or interrogations of the suspected perpetrators. Sometimes there would be 'official' looting when later kings 'tidied up' or moved earlier burials, either to make space or to protect them from other looters. People were understandably keen to stop their own burials being messed around with: a 3000-year old royal tomb in Byblos, Lebanon has an inscription halfway down the entrance shaft which has often been taken as a warning to intruders. The sarcophagus itself has a further warning: if anyone tampers with or disturbs the tomb, they will lose their power and authority and there will be no peace for Byblos.

The target audience seems not to be common thieves and looters, but kings and generals. It didn't work; the tomb had already been cleared out by the time archaeologists found it in the 1920s. Curses were a thing, then, and even without them, ancient burials and ruins would have been treacherous places, full of crumbling masonry and unexpected voids into which you could tumble without warning. It's easy to see how ideas could take hold that they were deliberately booby-trapped, gauntlets of trials but with fabulous rewards waiting for anyone who could successfully brave them. The booby-trapped tombs and perilous labyrinths of games might not be based on real history, but the fantasies and fears they tap into about the ruins of the past are very ancient indeed.