VR has already taken people with dementia to the seaside - and now video games are exploring neurological disease itself

From medical apps to indie games.

Mary is living with dementia at Belmont View, a Quantum Care home in Hertfordshire. Clearly distressed and disoriented, she is carefully led to a comfortable chair by carers. Once she is settled (though still visibly agitated), a virtual reality headset is gently placed onto her head.

"Ooh, look at it," she immediately says in wonder. Mary is sitting in a virtual beach scene diorama. The effect on her mood is dramatic; before long, she is singing 'I Do Like to be Beside the Seaside'.

Video games, and related technology such as this VR experience, are being used across the world to supplement treatment for - or better understand - neurological diseases. Neurological diseases are diseases of the brain, spinal cord or nerves, resulting in a wide range of physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms. Over the last few weeks, I've been speaking to several people involved in the applications of video game technology to neurological illness, and they have all had a fascinating tale to tell.

Mary is featured in a promotional video for the ImmersiCare experience, alongside other residents who describe it as "fantastic", and "beautiful". "It's always very emotional watching people, because of the happiness it brings," says Alex Smale, CEO of ImmersiCare. "A few months back, I spent about three and a half hours driving down to Southampton.... Seven hours of driving just for 30 minutes to actually give people the experience. And it was so worth it."

A typical ImmersiCare session will last 20-25 minutes, during which the patient will experience perhaps three different scenes in VR. (Carers are present throughout, to ensure that the patient is comfortable and not in any way distressed.) "There really isn't anything that comes close to the level of fulfillment and stimulation that VR brings with such a small amount of stress or difficulty," Smale explains. In addition to eliminating the stress of physically moving the patient, other scenes that it would be impossible to offer in the real world for reasons of cost or practicality - such as swimming with dolphins, or going into space - are also on offer. The sense of calm that descends during the VR experience can last for the rest of the day, and even into the night. Unsurprisingly, many residents enjoy sessions on a daily basis.

Dementia is a term that encompasses many different diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Benson's syndrome, Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA), and many more. Precise symptoms vary from person to person, but the common thread is varying degrees and types of significant memory loss. Confusion and mood swings are common, as is an inability for patients to recognise family members or - in the latter stages - themselves. Navigating previously familiar surroundings, using everyday objects, communicating with others - dementia can render these simple tasks extremely challenging, or even impossible.

Frustration and depression are all too common in those living with dementia. The ImmersiCare system does a wonderful thing in helping to alleviate that. Watching a participant literally cry with happiness as she removes the headset in the promotional video is not a sight I will soon forget. A quick and easy, albeit temporary, trip away from the care home is something that only VR can provide. It is, as another participant in the same video describes it, "like a free holiday".

Wonderful as it is to see people like Mary benefit from a therapeutic experience, it's extremely difficult to imagine exactly what it's like to see the world through her eyes. The symptoms of dementia aren't always visible, and are difficult to explain to anybody who hasn't experienced them. Video games occupy a unique space in terms of potentially being able to rectify this.

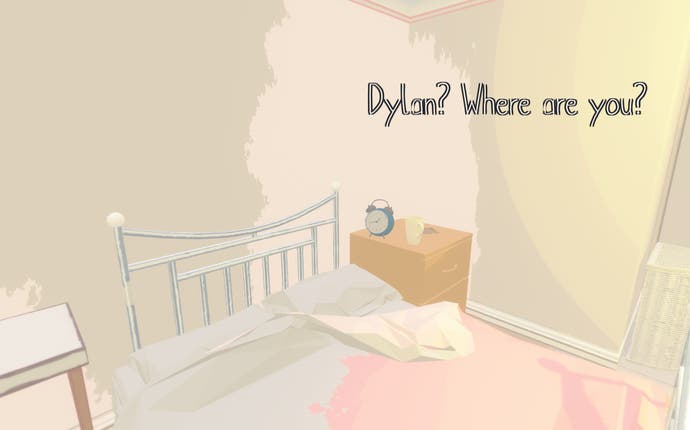

3-Fold Games is hoping to do so with its first game, Before I Forget. Still in development, it puts the player in the shoes of Sunita, a fictional character living with dementia. The player will feel the frustration she feels, see the hallucinations she sees, and discover the life lived that she discovers.

Narrative designer Chella Ramanan explains the basic concept. "It's a narrative exploration game, focused on a woman with dementia. You guide her around a house, and you interact with objects. When she picks up an object, it triggers a memory." Working with medical professionals Dr David Codling and Dr Donald Servant, the small team at 3-Fold are striving to make the experience as authentic and respectful as possible.

Ramanan proudly recounts a section of the game that the doctors found particularly representative of the disease: "We have a sequence where Sunita wants to go to the toilet, but she's forgotten where it is," she tells me. "So the player will go to a door that they haven't been to before. But every time they open it, it takes them back to the same place. This represents the fact that she's getting confused about which door leads where, and it's really interesting watching players dealing with their frustration at not knowing what's going on.

"That's a thing you don't normally want to do in a video game - frustrate your players - but that's obviously part of the experience of dementia."

Frustration is not the only reaction that their current build is provoking, however. Having finished playing through the demo, people often become very emotional, reminded of loved ones that are living with dementia, or have perhaps passed away. Claire Morley, a programmer and 3D artist, says that these reactions were, "pretty overwhelming to be honest, it was really flattering, in that we've made something that can elicit that kind of response; [it's] validating, in that we're making something that is worth making."

Ramanan agrees, and suggests it works toward their goal of reminding people that somebody living with dementia is more than their disease. "They're a whole experience of friendships, and family, and relationships, and careers, and hopes, and dreams."

Although a video game in the traditional sense, Before I Forget has the potential to be educational in the way that only a game or similar experience can. "We can do things that you wouldn't be able to do in a film or a book, which is play around with the player's sense of control," says Ramanan. And it is not only those living with dementia that video game technology can offer a bridge to, particularly when it comes to conditions that frustrate this sense of control.

Multiple sclerosis is a disease which affects the central nervous system, which is composed of the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms vary wildly, but commonly include difficulty walking, muscle stiffness and spasms, problems with co-ordination, dizziness and fatigue, and difficulty processing visual information. It is not a terminal disease, but it is incurable and progressive. Due to the sheer range of symptoms MS can lead to - and the great variability in how it affects people - MS can be a very hard illness to get a sense of.

Enter Merck, which has created MS Inside Out. This is another VR experience - with a full sensory version involving external stimuli, and a more traditional 'roadshow' version - that seeks to emulate some of the common symptoms of MS.

Andrew Paterson, Head of Neurology & Immunology at the Biopharma business of Merck, explains that the experience is so effective, its use is not limited to members of the public. It's also used to educate neurologists and other medical professionals about the condition that they're treating. More developments are on the way, for MS and beyond. "We've only scratched the surface of VR's potential," he says.

Though a product from and for the healthcare industry, MS Inside Out bears similarities to traditional video games, in that it offers two different 'stories' to experience using computer-generated graphics. Andrew gives an example from the tale of 'Tom', where something as simple as picking up a toothbrush becomes a challenge due to the fine motor skills required. "[the headset user] will try to pick it up, but they will actually miss. It becomes very, very frustrating very quickly. You can't actually do exactly what your eyes and your brain are telling you to do. What's being shown on the screen isn't synced with your actions [...] when we tested this and showed it to patients who have the same sort of experience, they felt it was a good representation of the frustration they feel trying to perform everyday tasks."

While more intangible elements such as euphoria and fatigue are not yet emulated in VR, Merran Boyd - who lives with MS herself - agrees that her experience with MS Inside Out effectively emulated many of her symptoms. "It gave a really good overview of some of the symptoms that I face daily myself. Things like visual disturbances, blurring of vision [...] I think it gave a really good, true experience of the symptoms it was creating. It put you into that mindset of someone with MS."

Boyd says that when her husband tried the experience, it helped give him a greater understanding of her daily life. And more generally, "I think it's good for people with MS to get a look at some of the symptoms they may not experience that others do, but also for the people who don't have MS to understand what others are trying to tell them about."

Boyd, and the millions of other people living with neurological diseases, are experiencing the world from a variety of angles that any one of us could find ourselves occupying at any time. For example, recent research suggests - as reported by The Guardian - that over a third of men, and almost half of women, are likely to develop dementia or Parkinson's disease, or to have a stroke. Add to that the estimated 100,000 people living with MS in the UK alone, and the myriad other neurological illnesses I have not mentioned here, and a picture of the prevalence of such conditions comes into focus.

ImmersiCare is proof of video game technology's therapeutic potential when it comes to such illnesses, potential which has only just begun to be tapped. By providing a virtual world to somebody like Mary, the otherwise impassable gulf between physical limitations and a desire for fresh, regularly delivered, stress-free environments is miraculously bridged. At the same time, virtual worlds such as those created by 3-Fold and Merck can paint a picture for those of us not currently living with a neurological illness - a picture that paints a thousand, often frustrated, words.