Thief: The Dark Project is 20 years old, and you should play it today

Nick of time.

As with so much else about Thief: The Dark Project, its legacy is wreathed in shadow. Thief's footprint is barely visible today, a world away from the fame of Grand Theft Auto or Metal Gear Solid or even Deus Ex. That's not to say it doesn't have its fair share of fans lurking in dark corners of the Internet. But even if you found them, they'd probably say you're better off playing Thief 2.

Yet just because you can't see something doesn't mean it isn't there, and if you know where to look, you'll see traces of Thief's legacy everywhere. It's in the shadows of Splinter Cell, the air of Amnesia, the DNA of Dishonored. It's in any game where darkness is your friend, where you can lean around corners, or as a former Thief designer once explained to me, where you save the world "by looking evil squarely in the crotch".

There are countless ways in which Thief could lay claim to being of the most important and influential games ever made. But I don't want to talk about legacy. Instead, I want to tell you why you should play Thief right now. Many games owe a debt to it, but there's still nothing like the original.

Admittedly, these reasons have little to do with the game's core premise. Thief remains for the most part a finely crafted stealth game. But what was revolutionary in 1998 was improved upon from the sequel onwards. Although ingeniously designed, stealth is simple and roughshod, and those accustomed to the breadth and flexibility of more recent sneak 'em ups like Dishonored 2 and The Phantom Pain may find Thief's roster of flash-bombs and elemental arrows somewhat anaemic.

Instead, the appeal of Thief today lies in what Looking Glass Studios built around its game of virtual hide-and-seek. And I literally mean built around. When it first launched, Thief's premise was enough to make it stand out from the crowd, and it could so easily have been an ordinary heist game. But it is anything but. One of the game's core themes is a conflict between the natural and the mechanical, and this is communicated through the levels, which are a blend of logical architecture and knotty organic design. The second mission sees you performing a daring jailbreak from a rigorously structured Mechanist prison. But the institution is built atop an ancient, twisting mining complex inhabited by spiders and shuffling undead. Another mission represents this concept more literally, as you explore an abandoned section of Thief's city rotting back into the Earth.

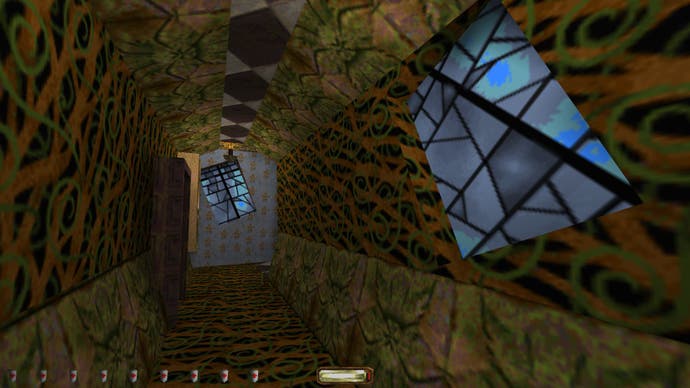

No level exemplifies the ambition of The Dark Project better than the Sword. Here you must "acquire" the eponymous blade from the mansion of an aristocrat named Constantine. On the lower floors, the house resembles a stately home, with large, opulently decorated rooms connected to an equally spacious garden. As you ascend to the higher floors, however, Euclidian geometry slips away, and the game begins to toy with your senses of perspective and scale. You'll walk into rooms where you're dwarfed by giant-sized furniture, along corridors that shrink until they're too small to navigate. In one room, the whole notion of shape vanishes entirely, leaving you suspended in empty space along a perilously narrow walkway.

It's not just the ambition that shines through 20 years of graphical improvement, or the brass balls of making something so fiendishly defiant of the player's will to progress, it's also so utterly, beautifully strange in a way that you rarely see in video-games these days. When modern games want to convey an unreal space, they do it in depressingly similar ways. Usually, this is some variation of floating islands (which represent the character's fractured sense of reality, in case that wasn't blindingly obvious). Recent examples include Spider-Man, The Evil Within, and even Dishonored.

Thief though, is genuinely weird, and it isn't merely the game's spatial shenanigans that contribute to this. Thief has a setting and atmosphere like no other. The City in which Thief takes place is an amorphous hybrid of medieval fantasy, Victorian steampunk, and early 20th century noir, a place where sword-wielding guards patrol under the glow of streetlamps illuminated by floating orbs, and where its stone-built prisons, mansions, and opera-houses are littered with mechanical devices like elevators and automated forges.

More important than how the game looks, however, is how it sounds. Thief's audio is a layered blend of electronic music and ambient noises designed to slowly seep into your subconscious, lending weight to the darkness that nearly always surrounds you. Often the soundtrack is simply emphasising the silence, deploying a rhythmic hum or a quietly howling wind to compound your sense of isolation, making each scuff and click of your footsteps stand out all like a tolling bell.

In certain areas, the audio provides a warped simulation of your environment. The cell-blocks of Cragscleft Prison are haunted by the groans and phlegmatic coughs of the incarcerated, while the gardens of Constantine's Mansion play home to strange insects whose chirps and buzzes are like an itch inside your skull. There's a wonderful loop that spins up when you break into Lord Bafford's Manor on the very first level, somehow encapsulating the feeling of sneaking around someone else's home in a couple of jarring chords.

Combined together, Thief's audio makes the very air feel like it's pressing down on you, trying to squeeze you out of whatever corner you're secreted into. Consequently, you're alert to your surroundings even when doing nothing other than waiting for a guard to pass by. It also makes the game utterly terrifying. Thief is not officially a horror game, but it is nonetheless up there with Amnesia and Alien: Isolation as one of the most frightening games I've ever played. The eerie atmosphere, the tension of the stealth systems, the creepy undead, which include babbling ghosts and sword-wielding Haunts who cackle maniacally while chasing you. It's terrifying.

Thief's cloying atmosphere would verge on intolerable, were it not for the lighter touches that the script deftly deploys throughout. This is most evident in Garrett, the master thief whose cowl you don for the duration of the game. Cool, cynical, and a touch arrogant, Garrett is a splendid anti-hero. But he's equally the player's companion, his wry observations and laconic wisecracks providing welcome reassurance when sneaking around places where everyone and everything can very easily kill you. Thief's bumbling, grumbling guards also contribute their share of comic relief, whether they're drunkenly singing to themselves or arguing about whether the bears in the bear pits are smaller than they used to be.

Thief is not a perfect game. Although the level design is generally brilliant, it isn't always that well suited for skulking around, while the undead creatures are difficult to sneak past because their body language is hard to read, and they cannot be knocked out. The first half of the game is also superior to the second, which lays on the supernatural too thick, and includes a couple of gimmicky levels that don't quite work.

All these issues were eradicated in the sequel, which is why it is often considered the superior game. I agree that overall The Metal Age is more fun to play, but it also loses some of the surrealism and dread that makes the Dark Project such an essential experience. Not only is its atmosphere and style unique within games, but its artistry simply could not be replicated by another medium. Thief's essence lies in the fact that it is experienced first-hand, crouched in the dark, clutching your blackjack, while a guard peers into the gloom right in front of your face and something in the soundtrack chitters in your ears.

That's why it needs to be played, not watched or read about (seriously, why are you still here?). Thief's legacy may be as a progenitor of the stealth genre, but the game itself is so much very more than that, and as such, it deserves more than simply to be remembered.