The brilliance of video game maps

Press X to mark the spot.

Hello! Earlier this year, Thames and Hudson published a beautiful book on literary maps. It's called The Writer's Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, and if that title doesn't make you yearn for the kind of novels that come with mysterious territories scribbled across their end-papers, here's a lovely piece in the Guardian to give you a taste of this wonderful, transporting book.

A few of us ordered the book to arrive on day one. And as we read through it, our thoughts inevitably turned to video games and their own relationships with maps. Below you'll find some of the things we ended up thinking about.

The world is what it is - Malindy Hetfeld

A unifying characteristic of literary maps is that they turn a setting into a character. If a book includes a map then the world, or the journey you see mapped out within it, is pivotal to the story an author is trying to tell. Some video games use their maps in a similar way, to create a functioning world - most importantly, a world that functions without you.

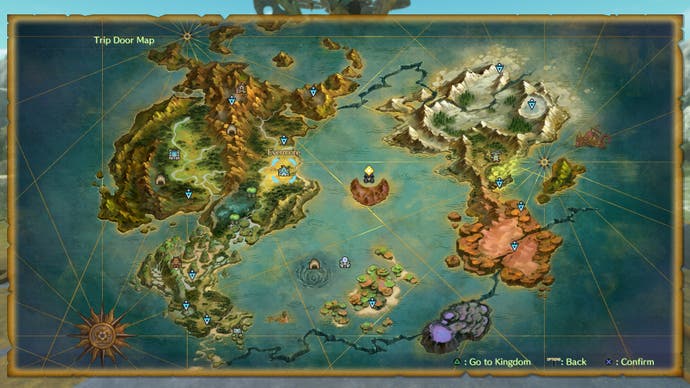

Most games afford players the freedom to create their path themselves. This doesn't only apply to open-world games. If I see an overworld map in an RPG such as Ni no Kuni 2, I expect to be able to travel to all of the places I see, and will likely seek opportunities to backtrack, too. Video game maps are mostly meant as navigational tools in the moment. They show you where you are, but they rarely show you where you're going. When we see an empty spot on such maps, we tend to assume that nothing of interest awaits.

In a world that has been designed with the player in mind who can literally go anywhere they want to, it can be difficult to hold their attention without specific landmarks. I admit that I love these fixed goals, because like The Lonely Mountain in the Lord of the Rings, they make you await your final destination with bated breath. In Link's Awakening, everything points to the Wind Fish's egg on top of Koholit's highest mountain. In Uncharted: The Lost Legacy - finally an Uncharted that makes use of a proper treasure map - the different towers you need to get to stand tall and proud.

However, it can be difficult to build emotional attachment to a locale in a game unless you actually get to see it yourself. Books have the time to establish the history of a place, even if it isn't central to a plot, in order to make the world as a whole feel more real. There are some games that manage this even if I only spent a few moments in certain areas as part of the plot: Final Fantasy X tells you a little about each place on the map, unfortunately only after you have visited it. It also has a historian who teaches you more about a town or historic battlefield once you arrive. By contrast, the map in The Banner Saga comes complete with informative little rubrics even for the parts you don't get to visit.

Dragon Age Inquisition is another example of a game that made me feel quite strongly for places that it did not allow me to visit. Different characters talk about different parts of the world of Thedas constantly to show you that your actions have far-reaching consequences. This way I can find out what happened to a town I have visited in a previous instalment, or learn more about lands I am barred from, such as Tevinter. I long to visit Tevinter, thanks to the evocative descriptions characters that grew on me provided.

The absolute piece de resistance of a game world map has to be the continent of Tamriel for The Elder Scrolls. People have tried to wrangle Skyrim's map into submission with mods and interactive versions of it, but it fundamentally is a map that doesn't explain itself to you or aspire to be particularly helpful. The world is what it is - now you have to go and find your way across it.

Misleading maps - Christian Donlan

In Spain this October, my wife and daughter and I set off one morning in search of a famous cactus sanctuary. Sanctuary is not quite the right word, of course, because succulents are hardy and the surrounding mountains suggested they could survive in even the worst conditions, clinging to the loneliest spire of distant rock. But Sarah loves them, and the nature of her love makes them feel, in some strange way, as if they are in need of sanctuary. How could she love something in this peculiarly delicate manner if it wasn't vulnerable, embattled, in need of a hug? Well maybe not a hug. Not for a cactus.

Anyway, we set off and quickly discovered that the map we got at the hotel was a highly abstract thing filled with whimsical compressions. Long roads in the real world were very short on this map if they didn't offer much to look at. Mountain paths with excellent views down onto the sea might be a few meters in real life, but this map elevated them to glorious causeways. After a few minutes, we got out Sarah's phone, and I led us all - I don't know why it was me doing the leading; Sarah's the fearless and practical one - as best I could. We turned on location services and suddenly we were a little blue dot moving along a blue line. We made the thirty minute walk to the cactus sanctuary in around fifteen minutes, without mishaps.

And without, in fact, much of anything. The minute the phone was produced I started to walk quicker, we spoke less, and - funny thing this - the landscape seemed to utterly disappear. We were staying just above Barcelona in the middle of some of the most wonderful coastal territory imaginable. The path to the cactus place was not a straight line but rather a lovely sinuous arcing thing, a dancing, flexing Bezier. But I saw very little of it because I was looking at Sarah's phone. I didn't need the real world anymore.

Except for one section, anyway. Briefly, as we moved from the edge of the town into a sort of fancy mountainous suburb filled with huge mansions perfect for any passing oligarchs, the map and the landscape briefly pulled away from one another. The blue line of the street on the screen was a little shorter than the dusty stretch of actual street beneath my feet. For a minute or two I had to favour the real world over the virtual, although I did it with great reluctance and distrust. For that minute or two, I suddenly had to look around, and how pretty it all was, how wide and open the sky, how warm the sun.

And then we turned a corner and the whole thing snapped together again and the world disappeared once more.

Looking back at this, what I can't help but think about is the huge sprawl of modern open-world games, the beauty and artistry, the carefully crafted views, the tangle of natural systems that create wildlife. All of that, and how little I notice it, because I am on a mission all the time, and I am an arrow on the tiny, unsatisfying mini-map, but the mini-map is entirely accurate and so I only really need the arrow and the map and the real world itself is an irrelevance for huge stretches and so I pretty much tune it out.

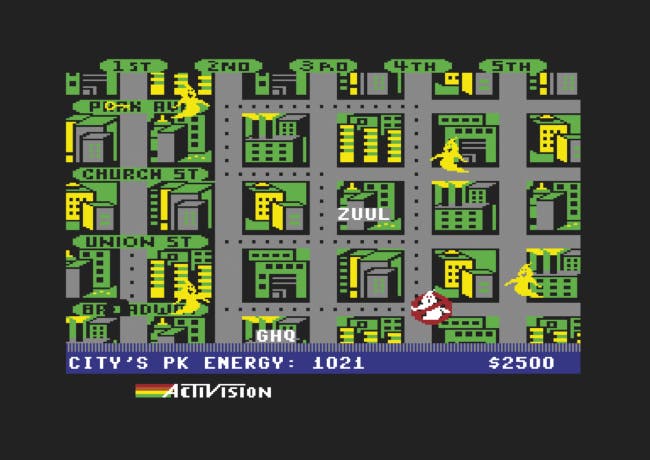

This can't be a situation that pleases anybody. Games have become much easier to complete, I guess, since we got mini-maps and waypoints. We all laughed when those glowing chevrons turned up in Perfect Dark Zero, but they were heralding an era of games where being lost was no longer allowed. BioShock! You're under the sea in a fascinating failed experiment of a city where monsters roam and secrets lurk. Do be a dear and follow the golden arrow at the top of the screen? Nobody was laughing then, but that golden arrow ruins BioShock, and I don't know whether they should be ashamed for sticking it in there or whether we should be ashamed for needing it.

Anyway, the moral of all this is that the cactus sanctuary was absolutely amazing and you should definitely go there. There's a parrot named Stuart and the people who run the place all seem cheerfully eccentric, and there really are an awful lot of succulents knocking about.

Oh yes, and abstracted, misleading maps - maps that require a bit of work - are much more fun than accurate GPS maps, and maybe they should turn up in games more often. It will take longer to do things, but I might remember more of it afterwards.

Indigo Plateau, Kanto's great counterweight - Chris Tapsell

I think the best maps - in games, that is, but I suppose out of them too - are a lot like the best stories. The whole maps-as-storytellers schtick isn't really anything new, of course - Tolkien started with the map, apparently - but there's a very specific type of storytelling map I have in mind: the type of map that has an end, and not just an end but, like a good story, an end that you probably always knew was coming. The best maps I've ever found in games don't tell you where to go, so much as they tell you where you are going to go, sooner or later, like it or not.

I'm thinking about Pokémon, of course. I'm always thinking about Pokémon, although in this case though I do actually have a reason for it because Let's Go, the wonderfully sugary reimagining of Pokémon Yellow, was the most recent game I spent hammering away at for one of our guides and, naturally, that meant spending a lot of time looking at the map.

Only it didn't, really. Normally assembling a guide means constantly back-and-forthing between the map and the world itself, taking pictures, making notes, writing up locations. But I hardly ever use the map in Pokémon games. Why would I? Pokémon games, despite the illusion of an open world around you, are oddly linear. Someone could probably argue that they're Metroidvanias, actually, and they'd probably have a point: squiggly spaghetti lines that unlock and transform and circle back, a knot that tightens if you try to fight it, only opening up if you follow it, wherever it wants you to go. But unlike Metroidvanias, and unlike many games, really, Pokémon games make a point of not just telling you but showing you, right away, where you're going to end up.

Indigo Plateau, where you fight and, inevitably, beat the Elite Four to become your region's Champion, sits in that top-left corner of Kanto like a great counterweight, so heavy it's got its own gravitational pull. Dither, sure. While away a lifetime on the soporific shores, fishing in a lonesome corner of Route 10. Keep bumping into those big, immovable rocks that line the water routes in the south, hoping to somehow will your way onto the other side. Take as long as you need, but try as you might to go off-script, you will end up at Indigo Plateau.

I love that. I love how it dilutes the great, galactic complexity of storytelling down to something so simple but so compelling. 'Characters going from A to B'. Such a horribly boring, mechanical way of thinking about how stories work - but one that's still pretty much right, at least if all my half-read screenwriting books and many, many nights spent with head firmly on desk have taught me anything. Plot is things happening, story is things happening in a direction. Repeat that five times and then put it in big red letters on a flash card. Dodgy screenplays aside, it seems like a device that's still so woefully underused. Especially in games, of all things, where you often spend so much time flicking back and forth between map and world it can feel like you're playing the map instead.

There are other games that do it though. No Man's Sky and Into the Breach. Total War Warhammer 2, with its big unignorable vortex. Breath of the Wild and its ingenious dismissal of that old open-world dilemma, putting you on cleanup duty after the end of the world, instead of pitching the chaos all around you while you opt to roll cheese down a hill.

FTL is maybe the perfect one: a game that builds the thrill and tension into the plotting of a course, when all the while that little red dot sits there at the end of it, just patiently waiting while you're off tarrying in the far reaches of a friendly sector. But the effect in all of them is the same: it makes the quieter moments, that you take for yourself, all the sweeter. I'll get to you shortly, little red dot. Just like Indigo Plateau, just like Ganon, and just like the original Mount Doom.