On the awful thrill of a good maze

Come in and get lost.

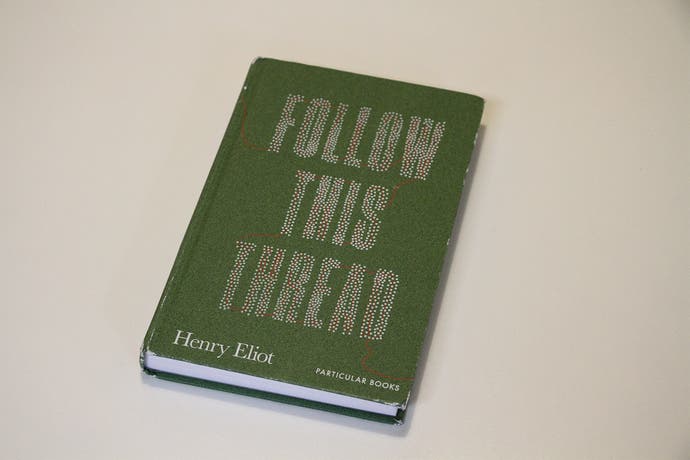

Last year, I read two really wonderful books about mazes: Follow this Thread by Henry Eliot, and Red Thread: On Mazes and Labyrinths, by Charlotte Higgins. I can't stop thinking about them. Eliot is the creative editor at Penguin Classics (if that makes it sound like the best job in the world is already taken, I regret to inform you that I think it might be), while Higgins is the chief culture writer for the Guardian (oh dear, the other best job in the world has been filled too). As you might expect from the titles, both books use the tale of Theseus and Ariadne as a means of launching beautifully constructed tours through the overlapping worlds of art and literature and mythology and human chaos.

And Eliot's book has something that makes it particularly interesting to people whose minds are filled with games. At the heart of Follow This Thread is the story Greg Bright, who emerges as one of the greatest, and most daunting, maze designers in history.

According to Eliot's book, it was at Glastonbury in 1971 when Bright, who was 19 at the time, first considered building a maze. He immediately asked Michael Eavis if he had a spare acre or two of land that he could use to try his hand at creating one. Bright said later that Eavis probably expected him to camp for a week or two and then move on. Instead, he spent the next year in a field that was "too wet for...cows", working without a plan at first, and "concerned with the rhythms that would be imposed on the maze walker". The music of chance!

Eliot explains that this initial maze of Bright's also lead to the first of his maze design principles. While the entire field was a single maze, it was composed of a group of smaller mazes. Bright called the junction points for these mazes "mutually accessible centres." (Over the years, other principles were to follow, all with cool names like "partial valves" and "ghost telepoints".)

This Glastonbury maze is now long gone, but as a result of it Bright got the contract to make the huge maze at Longleat - a "fiendish" maze, according to Eliot, which was such a hit that it kicked off a mini-craze for maze constructions. Soon they were being built in parks and country house gardens and on public land across Britain and the rest of the world.

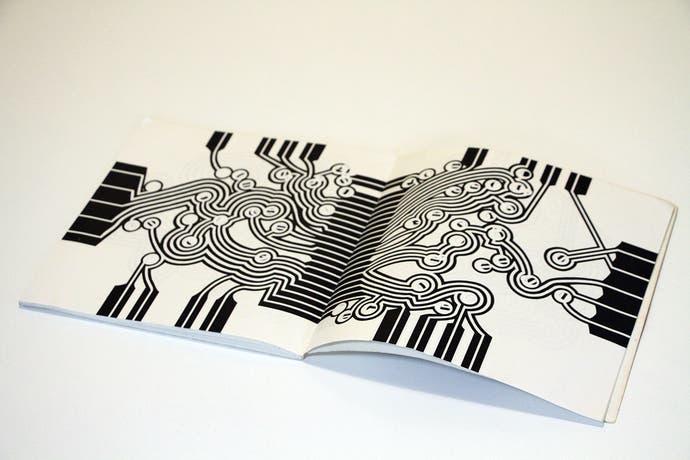

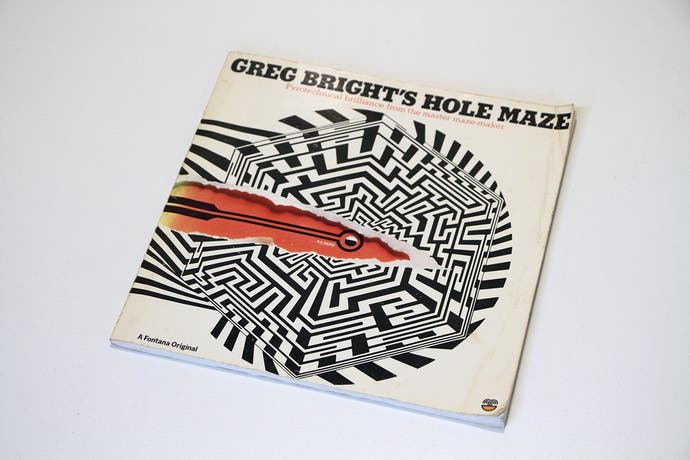

Bright himself quickly moved on to paper, "liberated...," as Eliot puts it, "by the lack of physical constraints." Exhibitions and publications followed, culminating, in 1979, in Greg Bright's Hole Maze, a dizzying monster of a book. "I saw it being readily deciphered by the first aliens from Outer Space," explained Bright. "Or by some mutant Newton of the dolphin species."

The Hole Maze is a fascinating document, and also a slightly frightening one. Early on in his tale, Eliot observes that "mazes are not comfortable places," and I have rarely seen a book as uncomfortable as Bright's. "My third maze book," he all but sighs in the introduction. "When it was the last thing I wanted to do, it became the next thing I did." And what a thing it is. Seemingly straightforward single-page mazes soon give way to complex lattices of light and dark lines. Holes are punched through pages and complexity lands upon complexity. When I turn the last page (never having ventured to make even the first decision required to start moving through the maze) I always feel like I am emerging from somewhere cold and treacherous. I often feel like I have a migraine coming on too. I can feel it advancing towards me over the channels and ridges of ink.

What to make of such a work? "In any quest there is a risk of overachieving," notes Eliot. "And Greg's fascination with the graphic purity of mazes was beginning to make his work less and less accessible." In 1979 Bright stated that the mystery of mazes, the aspect that once drew him to them, now "particularly disgusts me." That same year, Eliot reveals, Bright pretty much disappeared. "He published no more maze books and never built another maze."

After learning about Bright several years back, Eliot was determined to track him down. They met, eventually, at Bright's home, the location withheld and the house itself hidden behind an unkempt garden. Bright is 60 by this point, and shows Eliot his art and parts of a "vast, fragmentary novel-in-progress." "Concomitant with the fragmentary nature, which seems as much endemic as contingent," Bright explains, "the chapters are highly autonomous and heterogeneous, not to mention heteroclitic." I am going to sit down properly one of these quiet winter evenings we're currently having, pour myself a tall glass of Lucozade, reach for a paper and pencil (and some co-codamol) and work out what Bright's saying here.

More generously, when Eliot points out that Bright's work seems to require the restrictions Bright places upon himself, Bright says something absolutely glorious. "If there's no law, there's no tension with the law, so one thing is as good as another, there's no hierarchy any more. Whereas if you negotiate these difficult constraints, then something is accomplished by that negotiation.

"It's like with Bach," he concludes. "What, for me, Bach does, is make the law sound like freedom."

In the back room of Bright's house, he shows Eliot a piece of paper that covers an entire wall. "It showed a vast circle of tangled, overlapping paths, ending in hundreds of circular nodes," says Eliot. "It was recognisable as a maze, but only just..." This is the third iteration of Bright's "Ghost Telepoint Mazes", and as we leave him, Bright admits that "there is a deep problem about the audience" that he faces in his later work. He is working in mazes at such a high altitude that nobody can really follow him up there all the way. "Unfortunately," he says, "everybody but me is a lay audience in this."

After reading Follow This Thread, I emailed Eliot (full disclosure: I should mention here that Penguin, which publishes Follow This Thread, also publishes my own book) and went to visit him in London. I wanted to ask him about how he came to put Follow This Thread together, since it's a deeply unusual book in ways that I will get to in a minute. But I also, I think, and more fundamentally, I wanted to double-check with him that Greg Bright is real. Even after I picked up a copy of his Hole Maze book from eBay, Bright himself seemed like such a perfect literary confection, such a wonderful kind of trick - something out of Ishmael Reed or Paul Auster.

"That's so funny," laughs Eliot when we sit down together. "I haven't heard that reaction before, but it's an amazing reaction." Has Bright read Eliot's book? "He has a copy," Eliot nods. "I heard from him straight away. A letter that was very positive, I think."

I ask Eliot if Bright actually speaks the way he does in the book: highly autonomous and heterogenous. Not to mention heteroclitic. "Some of the letters I have had from him, I read them once and I can't make them out," Eliot replies with obvious admiration. "Once you work out the vocabulary, what he's saying is perfectly sensible. And often really insightful." He thinks for a moment. "I think there's definitely a streak of genius in him."

It turns out that, after struggling to track Bright down, Bright then cropped up in the most unexpected of places.

"I met him in 2011, and for the last two years I've had this job here with the Penguin Classics list," Eliot explains. "And one day I got this letter on my desk, just addressed to 'Penguin Classics, Penguin'. It could have gone to my colleague Jess, or to our assistant. But for some reason it was on my desk. I thought I recognised the handwriting.

"And it was a letter from Greg Bright," he laughs. "It was an extremely niche query about this line of Greek that Coleridge includes in his prologue to the Xanadu poem. He thought one of the diacritical marks was wrong and he wanted to use it in one of his poems and he wanted it checked.

"It was so weird. I mean, maybe he fires off letters all the time, but this guy who was so hard to find, and then by complete chance I got a letter from him at work."

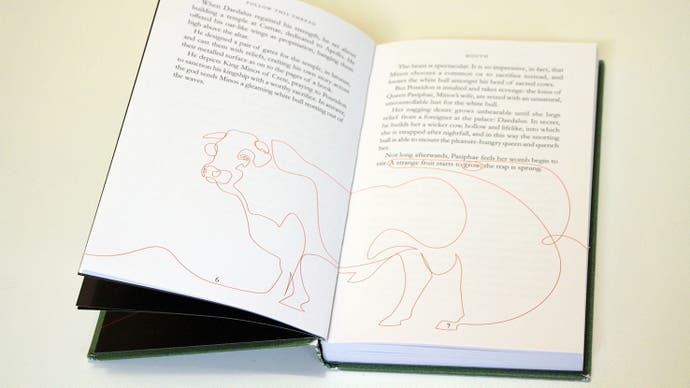

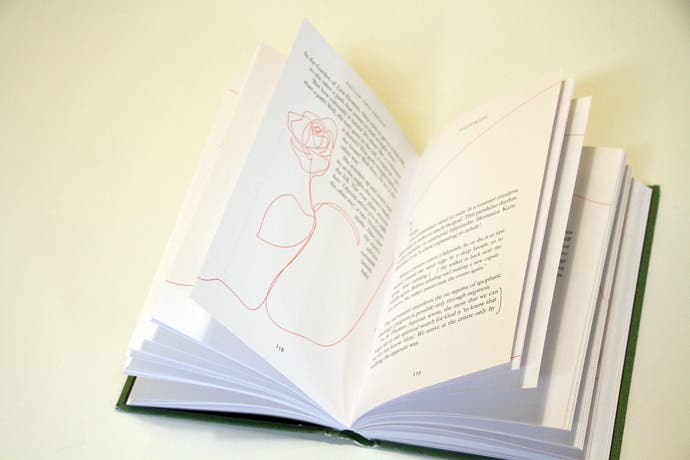

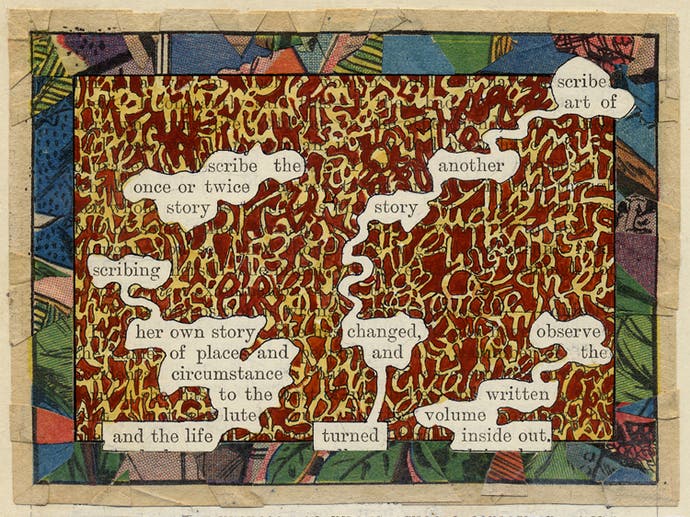

Even when Eliot's book isn't directly concerned with Bright - and it's a wonderfully restless book that delights in many different things - there is a sense that the maze designer's presence is always there, like a voice coming through the wall from another room. As with the Hole Maze book, Follow This Thread can be thrillingly odd and disconcerting, its narrative twists and turns mirrored as the text shifts through various orientations on the page. At times, you're turning the book as you follow a rogue sentence, and while re-reading it on the bus into work this morning, I got a few funny looks from people who wondered why I was reading a perfectly good book upside down.

Most intriguingly, through the entire book, Ariadne's red thread tangles and sways and wriggles and arcs across every page, cutting sentences in half, circling a world, or knotting itself into delicate illustrations of the people and things being discussed. More than anything, it makes me think about the act of reading - no, about the act of comprehending what you're reading. That thread seems to render visible the some of the contours of mysterious process that turns someone else's words into thoughts in your own head. (Oddly, Higgins' book is excellent at this too.)

And it makes me wonder: is this the sort of book that changes the way you see the world around you?

"That's definitely a thing towards the end of the text," says Eliot. "The idea, the slightly scary idea, that this structure which is so enduring and so full of different and sometimes contrasting metaphors, can expand to envelop the whole world and can start to feel like you can never escape the maze and that each aspect of your life can become a maze.

"There's a fantastic poem by Edwin Muir, which I only annoyingly discovered after finishing the book. It's from a phenomenal collection he wrote called Labyrinth, and the title poem is called Labyrinth, and there's a description of Theseus after he's left the labyrinth feeling like any road he's on, he's conscious of the choices he's making and the invisible walls he's walking between. It's this terrifying vision."

When I first read Eliot's book - and Higgins' Red Thread - I started to wonder why mazes have such a rich and enduring life as metaphors.

"I think that is the question really," admits Eliot. "I think that's why I wrote the book. One of the things that I do find fascinating is that mazes, as a physical structure or a design, only emerged 600 years ago, but the idea of them is so much older. You know, these various myths, the minotaur. That is what we'd describe as a maze, but it's so much earlier than the archaeological evidence. So this idea is incredibly persistent."

He tries another path. "Well, in a way that a chess board is an abstraction of the battlefield, perhaps a maze is an abstraction of the world. Because daily experience is an experience of making choices, feeling that you could have done some things better, being proud that you did something quicker than you might have, of coming up against barriers and meeting dead ends. And so I think that idea lends itself to the human experience of the world.

"And particularly, once mazes were being built, from the 15th century onwards, they're very unusual in that they're a metaphor that also manifests itself. Even if you don't go in there's still a possibility of physically entering this metaphor, or this symbol, which is quite unusual I think. I can't think of another symbol that can literally envelop you. It's interesting that the etymology of maze, is from amazement, bewilderment. In a sense it's quite a static word, of being taken aback and being bewildered by something."

Speaking of bewilderment, one of the things Eliot's book captures really beautifully is that, as a species, we don't actually seem to know how we truly feel about mazes. If we're visiting a country house, we'll maybe think, Ooh, let's do the maze, but Follow This Thread also points out that the first maze designs are found in a book of weapons. In the myth of Theseus and Ariadne, the labyrinth is not a particularly cheery structure. I can't think of many other things which are simultaneously "This is lovely, let's do it on a bank holiday", and are also "This is terrible and futile and we're all doomed."

Maybe our inability to fit these two aspects together is why we can't let them go?

"That's it," says Eliot. "That's the other part of it. They're so contradictory. And even in the experience of doing them you experience those contradictions. There is something very enticing about the entrance to a maze: you're curious and then the challenge of the puzzle is exciting. But then once you're in them, and I say this in the book, I feel quite claustrophobic quite quickly. Once you realise you've actually lost your way or you've made a mistake or you don't know what you're doing, all of a sudden it can feel quite terrifying, like a trap.

"And it's interesting that the metaphors that we use it for are so opposite in many ways. Many cultures use them as symbols of death, whereas in Indian traditions and Native American traditions it's a symbol of birth and spiritual rebirth.

"I feel somehow, even when we're in a country house and we walk into a maze, somehow we're accessing those pretty deep-rooted metaphors." He nods to himself. "I just think it's a brilliant, brilliant moment, the opening shot of Pan's Labyrinth, where the girls is lying at the center of the labyrinth, there's blood dripping out of her nose, but it's running backwards. Time in that moment is running backwards. And so we see the moment. Usually life is a one-way trip and we go from life to death, but what we see in that opening shot is the moment of death reversing back into life.

"I feel something like that happens at the centre of a maze. We turn 180 degrees around and all those metaphors of being trapped and heading towards a dead-end and death at the centre? We consciously reverse all of those by turning around and heading out."

Thanks to Paul Watson for the photography.