Why some special games are a bit like cooking

Delicious!

I don't know if you've ever tried to caramelise sugar, but trust me: it's pretty magical stuff. You measure your water and your sugar and you dump them into a saucepan. You swish it around until the sugar's gone. Then you put the saucepan on the heat. After a while, stiff little bubbles start to form. After a little while more, the pan is filled with them. The temptation to do something at this point is almost unbearable. But resist it! After a few more minutes, something astonishing happens. The clear liquid in the pan starts to transform. What was clear and thin slowly becomes thick and golden. Snakes eyes, pal: you've got yourself some syrup.

Change is everywhere in cooking, I am discovering, because cooking, I am discovering, is basically chemistry in the presence of a julienne grater. I made custard last week - actual custard from eggs and whatnot rather than from a powder or poured from a package. The last moment in the process, and I appreciate this sounds ridiculous, will stay with me. All of these ingredients and then you're heating and stirring and fretting and pretty sure it won't work. Then suddenly: man, that sort of looks like custard. It is! It bloody is custard!

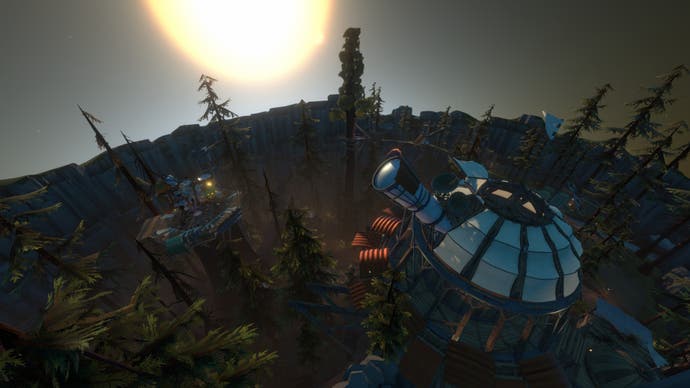

I will never forget the first time I struck custard, as it were. I will never forget the first time I caramelised sugar. And - gear change! - I will never forget the fact that while I've been exploring a lot of this stuff in the kitchen I've also been playing Outer Wilds. It's a game about exploring space in a dinky little ship and uncovering vast mysteries. It's physics rather than chemistry. But does it remind me of cooking? Sort of. And it makes my heart rise like a singing bird, because it's all about change, and change should be everywhere in games.

Over the last year or so I have started to group a small number of games together informally in my head. Vectorpark's games. Toca Boca's games, particularly Mystery House. These are games where things transform. In Vectorpark's world a window might open to reveal fur or a giant eyeball. A skeleton might rework itself into a xylophone. Up on the top floor of Mystery House, meanwhile, a selection of platonic solids go through a riot of different costumes, peeling open, squeezing shut, swelling, warping, cracking, ghosting apart. It took me a while to realise that all this prodding the screen and spinning the colourful doodads in front of me that I was doing? It took a while to realise that this was a puzzle. It seemed so smooth and flowing and gloopy and blocky and physical, so much like a process, rather than the cold digital calculations of what counts for a puzzle in most games. Then, it took me a while to realise that this puzzle was also something else. It was afternoon tea! It was cakes and tea and other sweet delights. It was all this stuff at once because it was change, pure and simple. As simple as the workaday alchemy of certain leaves placed in boiling water.

From this to Outer Wilds is not such a leap, I think, because as Vectorpark's Metamorphabet squirms and bucks with all the dark delights he has packed inside it, and as Toca's Mystery House can be pulled and squeezed and generally kicked around to colourful effect, Outer Wild's clockwork solar system is a place where huge forces are in play, transforming the landscape around you and frequently doing you in.

The container for all this change, as it were, is a time loop rather than a saucepan. You start the game at the beginning of a twenty minute countdown to an exploding sun. When the sun explodes - or if, as is frequently the case, your excursions kill you before it explodes - you come back to the start. This means that I started to see my little lens of time in this game as a process. It had a start state and an end state.

Or rather it has as many start states as it has planets.

Everywhere in the solar system you explore, things are changing. On a comet, the sun-facing ice melts away as the surface heats up, exposing a deadly interior. On a gas giant, huge storms whirl around a series of islands, changing their gravity as they move. On a two-planet system - I am sure I am using that term incorrectly - one planet slowly sucks sand from its twin. I parked my ship on one of these planets, and fifteen minutes later, I had stayed put while my ship had moved across to the other one. Meanwhile, as it travelled, I had been watching an ancient ruin slowly revealed as the desert beneath me started to shrink.

This is astonishing stuff. Dynamic stuff. Dynamic in a way that a lot of other games cannot manage. Change is everywhere in games, I guess, but it is so often binary changes: alive, dead, winning, lost. Games like Outer Wilds, games like the stuff made by Vectorpark and Toca, simulation games? They open change out into a sort of elastic continuum. These are games about flux, about the surprising shift from one state to another, taking in all the states between. They are games about physics and chemistry, about cooking, and about the panorama of life.

-45-57-screenshot.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)