How We Happy Few explores the injustice of motherhood

Mum's the word.

Be warned: the following article contains major spoilers for the first and second acts of We Happy Few.

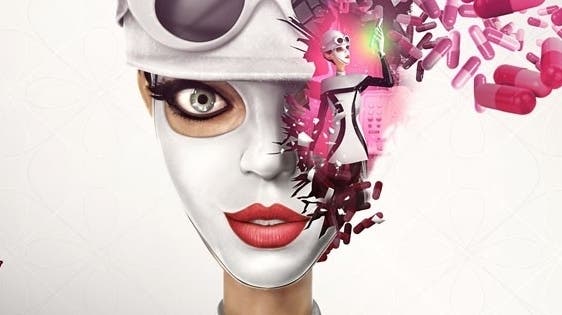

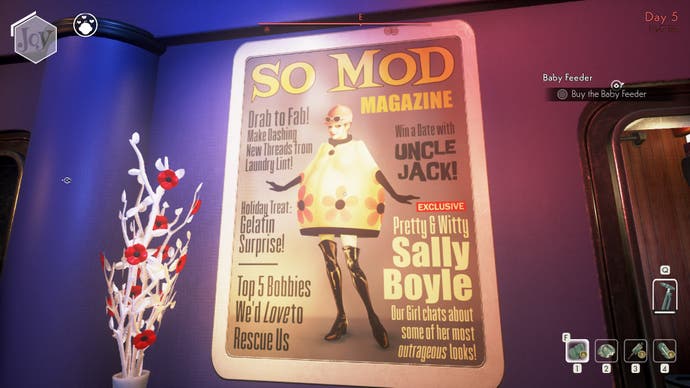

The first time you encounter Sally Boyle, We Happy Few's second playable character, it's through the eyes of a man. She strikes a dainty figure at the end of an alleyway, slick and trim in black latex and white felt, a jockey's helmet puckishly screwed down over thickly made-up elvish features. Within the game's 1960s British dystopia, Sally has become a sex and fashion icon, cast in the image of starlets like Edie Sedgwick, her apartment decorated with Pop Art prints of her own face. She's like something out of a fever dream, delightful yet abrasive and you sense, as reliable as the wind, hanging off your arm as she teases you about your clothes.

Sally's ditziness isn't entirely her own doing, however: the scene is as much a commentary on Arthur, the hapless dork doing the looking, as it is Sally. One of We Happy Few's more inspired tricks is that its protagonists perceive conversations with each other differently, the pulse of their emotions altering what is said and how. In the course of three parallel stories, played one after the other, you witness the same cutscenes from each perspective, with altered wording, performances and animations. It's tempting to say that there's no definitive account, but to my mind, the steady unfurling of the theme of censorship in Arthur's story (he once worked for the state's Department of Archives, Printing, & Recycling) makes his the least trustworthy. His impressions of Sally, specifically, are soured by resentment: the pair grew up together as foster siblings and were almost sweethearts, but fell apart when Arthur's dad coerced Sally into sleeping with him.

Arthur is nobly prepared to let bygones be bygones, however. Having acquired the means to escape Wellington Wells, he returns to Sally's apartment and offers to take her with him. She is receptive, but asks if it can wait till morning, glancing furtively towards the stairs - the implication being that she has another man to attend to. Arthur storms out in disgust, even as Sally protests that she has a secret to share. Hours later, the game switches back to Sally's perspective, and we discover what that secret was. Sally has a daughter, a squirming pink bundle of snot and tears named Gwen.

In the blighted post-War Britain of We Happy Few, children have been tacitly outlawed because they remind the population of certain unspeakable events; the mere thought of a child is enough to trigger panic and rage. Accordingly, Sally must keep her baby hidden in her flat, popping back to nurse her while holding down her day job as a leading purveyor of state-enforced "Joy" hallucinogens, and searching for her own way off the island. It's a bold premise in a very uneven game - not just a rare videogame representation of motherhood but a commentary on the stigmatisation and erasure of mothering at large. In the process, we also encounter a less gallant version of Arthur, the Nice Guy who blames an orphaned girl for his father's predatory behaviour. In her recollection of their parting, the scene has shifted to an overgrown playground where Arthur leans morosely, as though trying to sulk his way back into boyhood. As Sally perceives it, she actually tells him about Gwen, blurting the secret out as he turns away. "Did he even hear me?" she wonders. "Of course he heard you. He just didn't care."

While dad protagonists have enjoyed a spell in the limelight, playable mums in videogames remain few and far between. Those incarnations who aren't killed off to furnish a child or spouse with some plot momentum (see Far Cry 4, Dishonored, God of War) run a very small gamut, from self-effacing bystander (see any number of JRPGs) to suffocating tyrant (see ICO and Halo's Catherine Halsey). "It's a trope in literature that mothers often have to be dead for a young hero to go on an adventure," comments Lisa Hunter, one of We Happy Few's writers. "Presumably this is because a mom wouldn't let you go after Voldemort or take the One Ring to Mordor. When they are alive, mothers in stories are too often there just to scold and nag the hero. You seldom see a mom being a hero herself. But why not? Someone whose job is to literally keep someone else alive seemed like an interesting character to explore - particularly if her maternal role doesn't come naturally to her."

If the figure of the mother as a clutching harridan is more obviously grotesque, it's the caricaturing of mums as passive nurturers that deserves most criticism, because it perpetuates the long association of motherhood and, indeed, womanhood with free labour. As Girish Menon, chief executive of ActionAid UK, comments in a 2016 study, women worldwide effectively donate four years of work to society over their lifetimes by undertaking caring roles inside and outside the home. "Without the subsidy [this] provides, the world economy would not function," he argues. "Yet it is undervalued and for the most part invisible." According to a United Nations report from 2015, being a mum means taking a lifelong pay cut, rising for every child you have; the exceptions, it says, are mothers in some lower-income countries whose daughters are expected to help with the housework. Men, by contrast, are still generally not obliged or encouraged to devote the same share of their time to their kids, allowing them to plunge their energies into their careers and secure pay rises and promotions. As a result, mothers at work may feel compelled to minimise or hide the time they devote to their children, while younger women downplay their prospects of becoming mothers.

All of which is as true of the games industry as any other, but gaming puts its own, inglorious spin on things. On the one hand, there's the blockbuster sector's continuing reliance on crunch to meet unsustainable production schedules, which often comes at the expense of the family lives of developers - men and women alike. On the other, there's the macho association of "gamer" prestige with the ability to sink hundreds of hours into a game, and an accompanying disdain for "casual" games, including so-called "mom's games", which are designed to fit around a workload. As the independent designer Beth Maher told Gamasutra, while reflecting on her own experiences of motherhood, a player's ability to sink days into a videogame "doesn't have anything to do with how much they 'love' games or how much of a gamer they are, and everything to do with opportunity and privilege."

While hardly as gargantuan as an Elder Scrolls, We Happy Few is very much a game for the player with leisure time to spare, lasting up to 80 hours if you wring every last sidequest, crafting blueprint and character upgrade from its procedurally arranged world. As a survival sim that models the effects of hunger, thirst and fatigue, it also requires a hefty degree of concentration and planning - the coalescing of a mental map of resource locations, shortcuts, crafting tables and shelters. Survival games generally trade on a thoroughly alienated and self-absorbed vision of reality, in which the isolated player accrues mastery over punishing but intrinsically "fair" environmental variables. They are games that encourage you to make gainful use of everything, strip every possibility to the marrow and dispense with dead weight.

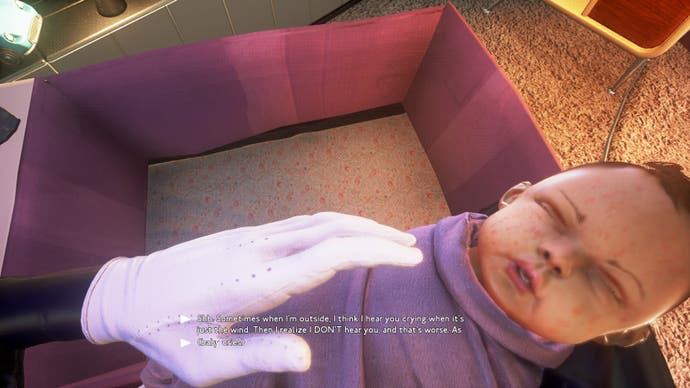

The presence of Gwen, however, troubles the rhythms of survival you'll have picked up while playing as Arthur, and thereby, the aloof and masculinist recreational culture those rhythms are geared toward. Caring for her is necessary to complete Sally's campaign, but that care is not a means to power or victory in itself. By chafing against the player's habits in this way, while presenting Sally's baby as her guilty secret, We Happy Few thus turns the disappearing and disparaging of mothers into a question of genre expectation: the frustration of a survival game's efficiency drive, in other words, doesn't just state but enacts the devaluing of maternal labour. Player reactions have been revealing. "On the one hand, some players are saying 'oh my god, I've got to feed this baby, it's terrible,'" says Hunter's partner and Compulsion's narrative director Alex Epstein. "And then other players are saying yes, that's sort of the point. Welcome to motherhood!"

Admittedly, Gwen often feels closer to a difficulty modifier than a child. For much of Sally's story, she appears only as an additional resource gauge at the top of the screen. Your interactions with her mostly consist of hurrying home between quests to feed her and change her nappy, which entails crafting a filter to remove Joy from the town's tapwater; you'll also need to tape together your own nappies, as these naturally aren't for sale anywhere. Epstein acknowledges that the portrayal of Gwen has come second to other production questions, such as reducing the load on animation and AI teams. The designers settled on a young baby, he says, because it would have been a nightmare to represent her moving around.

If she is something of a streamlined child, however, Gwen's needs are still provocative for how they disrupt the essentially anti-social fantasy of the survival sim. But her presence in the game is about more than complicating the genre's busywork - she also endows it with greater narrative and psychological texture. Gwen can be a solace for her mother where Arthur's only real companion in the end is the accusing memory of his lost brother. Cradle the baby in your arms and Sally will offer Gwen and the player her thoughts. These include reflections on her own mum, who very much conforms to the hysterical ogre stereotype, and Sally's resulting ambivalence about mothering in general. This ambivalence lends dramatic force to what might otherwise be some fairly generic survival game unlockables, designed to reduce the time players spend on certain activities as they become routine.

One of Sally's story missions involves putting together the materials for an automatic feeding arm, bolted to Gwen's cot like a budgie's water bottle. Besides letting you range away for longer, this goofily illustrates Sally's lack of sentimentality about parenting and unwillingness to sacrifice her autonomy to her daughter's upbringing. It feels like a reaction against the "culture of overbearing instruction and judgment" around motherhood, as described by Diana Evans. Yet Sally is not beyond the gravity of that culture, which is thrust upon her by We Happy Few's own system of buffs and debuffs. Every time you tend to Gwen, you'll receive a "Maternal Glow" buff that allows Sally to fight better, run further and go without sleep for longer. Shirk your maternal duties, and Sally will incur a "Burden of Guilt" penalty to her carrying capacity. This turns the game's own nuts and bolts into mechanisms of surveillance and reproach. You might read it as a blunt endorsement of the associated attitudes, but I think the buffs and debuffs are better understood as Sally struggling to escape the shame heaped on her during her youth and dread of turning into her own mum.

There is a sense in which Sally is mother to everybody in Wellington Wells. As Lisa Hunter points out, the state's unspoken forbidding of childbirth, together with the addling effects of Joy intake, has bred a society of overgrown toddlers. In the more affluent Parade neighbourhood, clown-painted townsfolk spend their days playing children's games such as Simon's Says, or coddling pets named for long-lost offspring; their nights are given over to lewd yet sexless, giggling orgies featuring full-body gimp suits and electric cattleprods. Presiding over everything is the marvelously condescending Uncle Jack, the daddy state made flesh.

Within this infantile milieu, Sally has grown adept at babying powerful patriarchs such as the odious General Byng, indulging their sexism and self-regard in exchange for access and immunity to arrest. Her appeal as a character lies with Compulsion's refusal to treat her as either saint or victim. "Like Arthur, she's a huge liar, and she manipulates people because she has to," Epstein says. "She's not among the righteous - she's just doing what she has to do." It's the presence of Gwen, however, that sets Sally's campaign apart and marks We Happy Few out as one of last year's most intriguing games, for all the well-earned criticism of its portrayal of mental health, and the leaden toil of staying alive within its world. In its raucous, crackpot way, it plays out the sidelining and belittlement of motherhood by entitled men, while also making a mother the heroine of her own story.