Snack Hacks, a cookbook for people who like games, is a strange delight

"You've been playing the Da Vinci Code video game for a few hours..."

"Chop the parsley," he writes, "just enough to discipline it." There is a poetry to a good recipe, a way of looking at the world that transports the reader. Fergus Henderson, the founder of St John, which is the greatest restaurant in the world if you ask me, is in the kitchen. He has some parsley. He wants to chop it. How much? Just enough...

That line rattles around in my head all day every day. Chop the parsley... I have been to St John several times now, and Fergus is always there at a table. Why wouldn't he be? If you've created the greatest restaurant in the world, where else are you going to head for lunch? I have read and re-read his cookbook, too, a vast white slab of a thing, pink fore-edges, a bit of texture to the cover. Mostly I read and re-read the recipe for bone marrow on toast. Chop the parsley, just enough, discipline. Wonderful stuff, parsley.

It's not just Henderson. Eat Me is my second-favourite cookbook, written by Kenny Shopsin, proprietor of a tiny restaurant in New York that I have always been afraid to go into because Shopsin often took against people instantly and denied them a seat at the counter. Shopsin died last year, sadly. He sounded wonderful. I still look in the mirror sometimes and see a person that Shopsin would have disliked. In Eat Me, right, he is telling you how to make his chili, which is the greatest chili in the world if you ask me. I make this chili at least once a month, I even have a cooking pot that I bought specially. And how hot should you make the pot before you begin? Hot enough, says Shopsin, to bounce a drop of water off the bottom of the pan.

This is magic. And there is a peculiar magic to cookbooks, one that has drawn me in so thoroughly that the next time I'm in New York I'm making a detour to Bonnie Slotnick's cookbook shop on East Second Street. A good cookbook gives me a particular feeling: it is a whole world, self-contained. It is a way of thinking, a way of seeing.

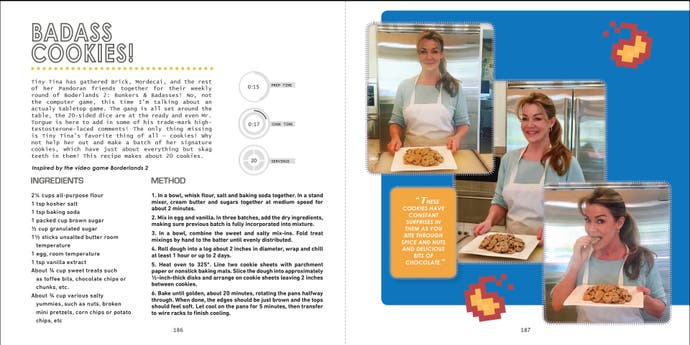

So I was excited to get a copy of Snack Hacks, which is a cookbook for people who like games. I like games! And I like cookbooks. It's written by Claudia Christian, most famous for Babylon 5, I want to say, but who has also done a lot of voice work for games, and by Mark Michel, a writer and photographer who has been playing games since the 1970s, according to his bio. It offers "over 100 fast and delicious recipes for gamers, coders, freaks and geeks".

I am going to be pretty direct now: this book won me over. And it had quite a lot of winning over to do at first. The paper stock isn't great, and the premise feels a bit thin - food for people who like games? Furthermore, the kind of food that Snack Hacks celebrates is not easy to make beautiful in photographs. Speaking of photographs, Claudia Christian holds an Xbox controller on a couple of pages in the manner of one who has been told it is filled with ants. And yet! And yet!

The point - and it took a while for me to realise this - is that the food in Snack Hacks looks like actual food. This is completely honorable really. I am on board. The winning-over had begun.

Also, I have made a few recipes and they are not bad at all. Snack Hacks, as the title suggests, is about immediacy and cutting corners. Some of the hacks are pretty clever: I had never thought to turn a muffin tin over to shape taco shells. Many of the recipes are simple and fun. Dragon Kickers Chicken may look like a pancreas - it did when I made it anyway - but it's really just buttermilk chicken with hot sauce and Italian breadcrumbs, unfussily rendered. This is not going to go wrong. I also like the fact that this recipe is a chance for someone to talk about God Hand.

This is a generous book, by the way. Lots of boxouts and asides that are worth reading. A bit about Claudia Christian's work recording audio for games, a page about Mark Michel's experiences growing up with cerebral palsy. There are voice artist actor profiles and a load of tips for storing butter. I would also have loved to have been in the room - and I really mean the love, I adore this stuff - when people were working out how to link a specific recipe to a specific game. Of course palmiers can be lumped in with the Da Vinci Code game! "Now you're getting hungry for something just as tasty as the mystery!" The recipe in question, for Ambigram Palmiers, is simple and adaptable, and it references ambigrams, which are a strange delight in themselves, so it's money in the bank all the way.

And it makes me think. It's taken me a while to realise that cookbooks and cooking are not quite the same thing. They offer different pleasures, and they occupy different spaces in the mind. To put it another way, I have memories of food, but I also have memories of cookbooks, and they're separate.

I grew up in a house that had The Joy of Cooking on a shelf in the kitchen, battered, spine gone to thread, notes and paperclips sticking out all over the place. I have my own copy now, and I know a bit about the rather moving history of this book, and its eccentricities, like the squirrel-skinning illustration that tells you you've got the best edition of the text. My daughter will grow up in a house that has Eat Me and Henderson's Complete Nose-to-Tail on a shelf in the kitchen. Somebody, maybe, will grow up with Snack Hacks on a shelf. This charming book of ugly food that is simple to make and tastes surprisingly nice is everything a cookbook should be: generous, precise, enthusiastic, partisan. For me it's a bit of a pleasant curiosity, but for somebody out there it might one day be the start of something brilliant.