My lost childhood with Daley Thompson

Infinite runner.

So: another day, another lot of newspaper hand-wringing over video games. Recently, Telegraph columnist Celia Walden wrote a piece in which she despaired over the recent Fortnite World Cup. With little knowledge or actual evidence, she ended her opening paragraph with the words, "I can't begrudge Jaden Ashman his win. But I'm also convinced that video games like Fortnite will be responsible for so many lost childhoods." It's as though children have only just started to spend time obsessing over multiplayer games together. But they haven't.

During the long hot summers of the mid-1980s I was a young kid with a bad haircut and a good Commodore 64 games collection. I didn't want to go to the park with the cool boys to play football and smoke Silk Cuts which was fortunate because the cool boys didn't want me there either. From roughly the ages of 12 to 16 I wanted to be Madonna or Sigourney Weaver or Jeff Minter and that was a confusing psychological bundle for other boys to unravel.

I was fascinated by sport - the rules, the rivalry, Ivan Lendl's Adidas clothing collection - I just didn't want to play. Fortunately I had computer games and a few nerdy friends. During Wimbledon, we would don tennis whites (I'm not kidding) and hang around playing Match Point on a pal's Spectrum. Sure, the animation was erratic and the ball boys looked like racist caricatures from a 1930s cartoon, but it was fast and fun and, if we took turns and kept score, we could get through the whole tournament before Knightrider started.

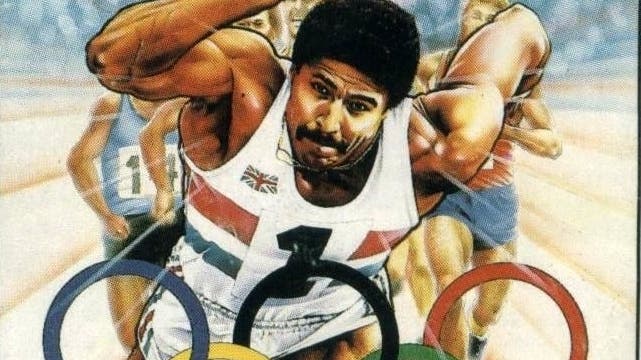

In 1984, there came the joystick wagglers. Daley Thompson's Decathlon was the local, everyman contender, with its devil-may-care approach to authenticity, and its advertising hoardings for brands we recognised from Stockport high street. Two players could compete in events such as long jump, discus and the 100m sprint, sitting close together their gripped hands in furious motion, like some sort of Public School initiation ceremony.

But the serious player's choice was Activision Decathlon, which was as glamorous and serious as Carl Lewis, and allowed four-players to take part. By the end of the summer, our bedrooms would be strewn with the broken shafts of a dozen QuickShot II joysticks, like the aftermath of an incredibly phallic space war. It was Activision's Decathlon that really taught me about the technique and strategy of track and field events, which sadly had little practical use because I'd already been banned from javelin at school for continually throwing mine while other classmates were still collecting theirs from the field.

The most wonderful days of my gaming summers, however, were spent with the brilliant sports titles from US publisher Epyx. Summer Games, Winter Games and the more wild and recherché World Games and California Games, were the pinnacle of multiplayer gaming in that era. These titles broadened the range of inputs, using joystick rotations and timed movements to simulate sports such as cycling and equestrian, and introduced a bunch of pale cheshire school kids to the delights of cliff diving and sumo wrestling. I swear these titles taught us more about the conventions and obsessions of other countries than a 100 social studies lessons - especially as we always bunked off social studies. Everyone bunked off social studies. Even the teacher.

What am I trying to say? It's simple. The idea of kids not going outside and instead sitting around playing video games, talking about videogames and reenacting video games, isn't new. Fortnite didn't invent it. It was there in the 1980s. And what's more, we didn't have lost childhoods. We were fine. I loved those days - gathering our snacks and sharing exaggerated anecdotes about our prowess in the kayaking; closing the curtains to stop the sun obscuring the crucial lifting off point on the Triple Jump; all standing and saluting during the medals ceremonies in the Summer Games titles; comparing joystick repair tactics. This wasn't lost time, it was just time - as light and disposable as all the other hours of childhood.

In 1987, I moved to Hemel Hempstead, which was poorer and rougher than my old home town of Cheadle Hulme. I finally started to socialise away from a keyboard and screen with people who'd had very different upbringings from me. It was there I discovered what the real causes of a lost childhood are - poverty and fear. In contrast, all I had were golden memories of loading screens and crisps and Nike casual wear. If I didn't fully realise it then, I do now, many years later. My childhood wasn't lost, it was blessed.