What does it take to truly know a video game location?

Mapping the wilds.

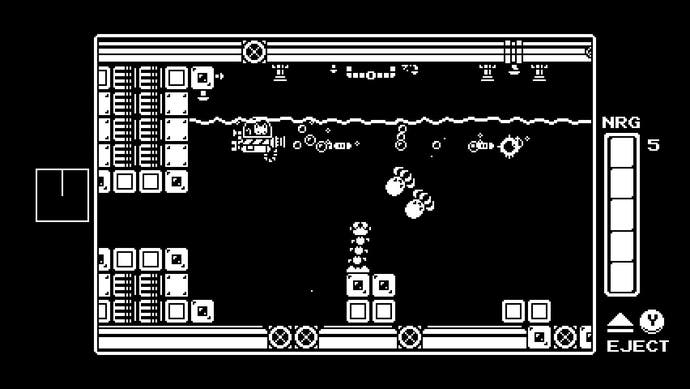

I realised the other day that I had probably played through Gato Roboto about five times by now. This wonderfully compact Metroidvania has grabbed me and held me close. It's the story of a cat lost on a strange planet, a cat who finds heroism deep within itself in a manner that feels very true to who and what cats are. It helps that the cat has a mech suit.

Normally, playing through Gato Roboto means starting from scratch, opening up the map, getting the basic items and chugging through the bosses. This time, though, on my sixth attempt I'm trying to do something I've never done before. I'm trying to 100 per cent it.

This has always struck me as a slightly tedious thing to do. I admire completionists but I've long known I will never be one. It always has the musty whiff of taxonomy to it. I want to get the gist of a game and see the end credits - people who skip the end credits are probably evil, incidentally - and then I'm generally happy to move on. But with Gato Roboto I've found a game that's sufficiently compact for me to test this whole completionist business out. And it turns out that I'm a massive dummy. There's nothing drab or dusty about 100 per centing a game. What I didn't realise is that it turns whatever you're playing into a whole different game.

Gato Roboto has completely changed now that I'm not just racing to the final battle but sounding out every environment I pass through. It feels like mowing a lawn, trying to get every part of it covered, and it turns the whole thing into a bit of a puzzle game. Whereabouts, in everything I've seen so far, is there a possibility for something I haven't seen? Which walls will give way? Which spaces seem a little too empty?

Ultimately, I'm learning the way that the people who made Gato Roboto like to think - what they like to do with space and how they like to create a rule and then subvert it. And the surprising thing is that it's changed my whole relationship to the game. It reminds me of Nick Carraway, newly arrived in West Egg and feeling like a bit of a nobody, and then someone stops him on the street one morning and asks directions and the whole thing is transformed: he suddenly feels like a pathfinder, a mapmaker. He feels a sense of deep knowledge, of connection to his surroundings.

Fitzgerald was playing this for laughs, of course, but I know this feeling, I think. With a handful of games I have come to know them so innately that loading them up does not feel like I'm going to play a game, but more that I'm returning to a place I am intimately familiar with, and that I care for to a certain degree. I feel like a custodian.

I felt like a custodian in Crackdown. This was a game that, I suppose, I pretty much 100 per cented without realising it. And once the game's main stuff was out of the way I was able to see the place more, somehow, to believe in its architectural fictions. The mountain sections of the first Crackdown felt like a non-place to me when I was going after the gangs or the orbs, they felt like an annoying between-place sludge to race through. With the game cleaned out I returned and for a while it felt like I lived there. I would bound over ridges, stumbling upon the Lighthouse, the Mansion, their in-game purposes long since removed so they could simply be themselves. In the end, when I now think of Crackdown, I think of these mountains. When you really get to know this game, the mountains are where the game's heart resides.

The other games I've come to truly know are all the other usual suspects I tend to find myself writing about: Grow Home - I know every inch! Link to the Past - the guy sleeping under the bridge! These are all games where the location is at first a handy space for the adventure to unfold in, but which becomes truly itself once the adventure is over. It has enough fiction - the fiction of nature, of rocks and trees and flowers growing in the wild - to keep you rooted there.

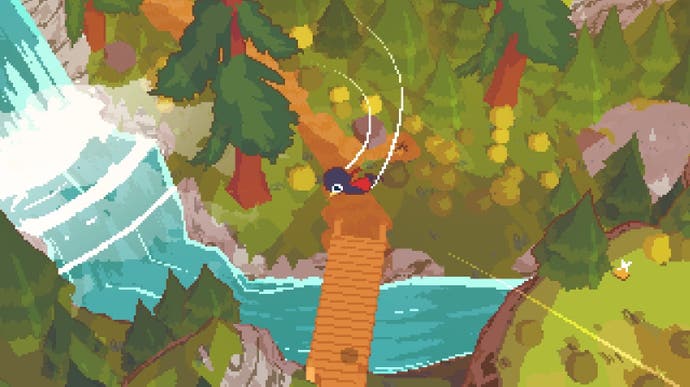

This is why I loved A Short Hike so much, I think. This is a game about getting to the top of a mountain, and you can do that in under an hour. Clearing out the rest of the game is taking me a bit longer, but as I do it, I am realising that I am rendering the landscape truly visible. It's like making a paper rubbing of it. I scour the surface of the game looking for coins and chests and feathers and collectables. And in scouring it, I somehow reveal to myself the fiction of earth and stone and sand and ice. When I'm done with this game, I will be ready to truly begin it, in other words. I will have my feet on the ground and the whole world open before me, and nothing to distract me from the wonders of a simple, singular place.