Someone should make a game about: Stanley Kubrick's archives

To Hal and back.

Hello, and welcome to our new series which picks out interesting things that we'd love someone to make a game about.

This isn't a chance for us to pretend we're game designers, more an opportunity to celebrate the range of subjects games can tackle and the sorts of things that seem filled with glorious gamey promise.

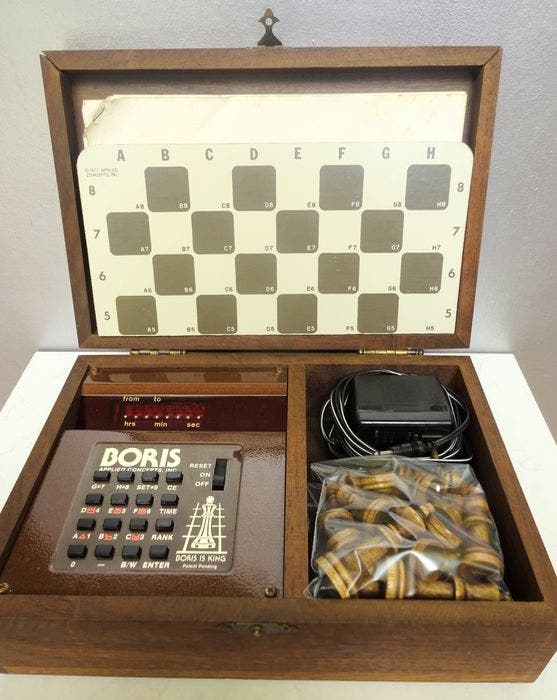

Boris is a chess computer from the late 1970s. God, it's a weird thing: this tidy wooden box with chess pieces and a fold-out board and a lump of computer, basically, a brown shiny brick of computer with keys and a little display. That display! Boris wouldn't just make moves. Boris would be a jerk about it too, typing out burn messages when you were up against it. Face to face with Boris a few weeks back, though, what filled me with delight wasn't just that here was a funny little chess computer I had never heard of. Here was one that had once belonged to Stanley Kubrick.

I am a proper Kubrick bore. Honestly, I am bloody awful about Kubrick. But like a lot of bores, it's because there is something about Kubrick that I feel everybody should get to experience. Over the years I have watched all the films dozens of times - I am the son of two Kubrick bores, for what it's worth - and I have also read a bunch of books on Kubrick and his films, including at least one biography, by John Baxter.

The problem with reading about Kubrick, though, is that you're often reading about someone who is reading about Kubrick. Because he kept to himself such a lot, Kubrick is terribly hard to get a handle on. I got a decent sense of the timeline from the Baxter book, and there are loads of lovely anecdotes in there, but the man himself did not quite emerge from the pages.

This is what made my encounter with Boris so special. Boris was recently part of the Stanley Kubrick exhibition at the Design Museum in London. I went up to see it a while back. Cor! The exhibition takes the form of 500 or so items from Kubrick's famously voluminous archives. You get a muddle of his early life and then a trip through many of his films, building, inevitably, to 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film so devastatingly good I absolutely refuse to get over it.

And here's the thing. After walking through this exhibition for a morning, I now feel like I have a bit of a sense of the man. And that's because Kubrick speaks directly through his things.

Example. Early on there's a bunch of stuff from his attempt to film a life of Napoleon. There are books and charts and art tests and all of that jazz. But there's also a huge box of index cards, actually a box of boxes. Look closer and you realise that Kubrick had an index card - I think I am getting this straight - for every day of Napoleon's life. When Napoleon was on form, there are multiple cards for a single day.

Who does that? Kubrick did. And for the first time I realise the probable reason that his Napoleon film never got made.

Later on, there's an image of the Overlook Hotel from The Shining. Kubrick is planning a shot of the exterior, but he doesn't leave England by this point and the exterior of the Overlook is in North America. So on the picture, Kubrick has written exactly what he wants. He's worried about the path to the hotel, the curve in the path. There's a way he wants it to be done. He breaks out the all-caps. "THERE IS NO OTHER WAY TO DO IT/REPEAT NO OTHER WAY," and, "the compositional effect of a different path might be BAD BAD BAD." When Kubrick tells you something might be BAD BAD BAD, this man who had an index card for every day of Napoleon's life, you probably took notice. But still, he has to stress it. He worries. He wants total control, but he also doesn't want to travel, so the result is anxiety, artistic fretting, directing via chopsticks.

One of the things that most stuck with me at the exhibition spoke to exactly this. It's the 1990s now, and Kubrick's planning Eyes Wide Shut. Eyes Wide Shut will be set in New York, but it will be filmed in London, according to the plan at least, so Kubrick despatches someone to photograph the entirety of a London street and tape the images together so he can see which bits he might use.

Part of Kubrick, in his thirst for total knowledge, part of him was waiting for Google to turn up. I had never realised that until I saw this image, which looks like nothing so much as a home-made Google Street View, which is, I guess, what it sort of is. Like a lot of things in the exhibition, the obsession, the desire for knowledge and control is heroic and slightly grotesque all at once.

I love reading about people. But I also love the idea of learning about them in other ways. The archive is a portrait, a self-portrait, and yet it is one that is constructed in part by the viewer, by the investigator. And like all self-portraits, there is the thrilling suggestion that it contains much the creator could not see for themselves.