Manifold Garden review - rewiring strange architecture in the void

Its roots must hold the sky.

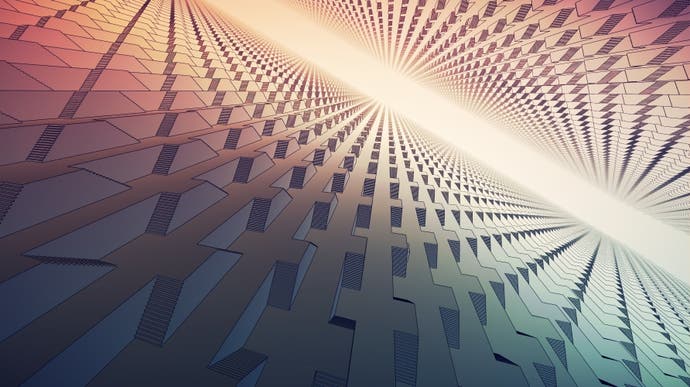

I wonder if Manifold Garden was born in that bright, strange moment in which a game world first wrapped around. You know, in the moment when Pac-Man first disappeared off one side of the screen, say, and reappeared - after a pause that grows more mysterious with every passing year, frankly - from the other side. The spaces in Manifold Garden are initially daunting. They're huge, bottomless, and the horizons race away forever. Then you start to think: Hey, isn't this corridor I'm walking down just suspiciously long? Then you realise that the real estate repeats, like distant trees in a Hanna Barbera cartoon, but freakier, because the loop has nothing to do with tiny budgets and everything to do with messing with the head. The world becomes a loop, but the loop looks nothing like a loop at all. The Slinky has been straightened. You can still see the trees that repeat up ahead, and behind you, and all around you. To proceed you must understand where you are already as much as where you want to go.

This is fun. Actually it is an astonishing amount of fun. When a solution to a problem in Manifold Garden finally becomes clear and turns out to be both audacious and simple, I often find myself laughing out loud. Game epiphanies can seem cheap sometimes: the music does this, the god rays do that and then you feel like the world has turned its face towards you and smiled a sleepy smile. But Manifold's Garden's epiphanies are not cheap at all. They are surprisingly frequent, sure, but each one stands for something, a little bit more understanding, a little bit more progress, a fresh way of viewing the world that had been obscured until now.

For the first hour, though, I was not convinced. Manifold Garden is a game about working your way through fantastical geometry, bending all things except logic and cause and effect. Cathedrals rise up out of the peachy void, the Lloyd Wrights mint atria and quadrangles from rose-coloured dawn. Always there is somewhere to go, somewhere to get to, a path that leads you forward, even if forward may look like upside-down, like inside-out, like backwards. But the game takes a while to teach you the things you need to know in order to get oriented. And so one of the greatest outdoors games of all time begins in poky little corridors and spare bedrooms.

What you're learning here is how to climb on walls, which can be done fairly easily by approaching the surface you want and pressing a trigger. Each wall you walk on is given a different colouring to allow you to orient yourself, and after a few puzzles you learn that you're not just changing the surface you can walk on but also the gravity of the world. Things fall to the floor around you, water streams in a different direction or simply stops. Most importantly, each surface, each colour, has switches and blocks that will only behave when you're standing on that surface.

The switches are basic enough. Blue surface, blue switch, you're off to the races. But the blocks are something else. For one thing they're actually apples, each one given the colour of the tree that grew it - the tree that, you've got this, shares the colour of the surface you're standing on. More importantly, you can only lift these apples up and move them around when you're standing on the surface that matches their colour. If you have to get one into a sort of lock thing to open up a door, that lock had better be part of the same colour system and floor the apple came from. Equally, if you're holding a red apple, say, and you move to a blue surface, you have to accept that you're going to drop the red apple where you stand and it will be fixed in place until you move back to the red surface again.

I wonder, dimly, if this is a riff on that funny quantum business of how each particular field corresponds to a particular particle. Sadly, everything I "know" about this stuff comes from reading the odd New Scientist magazine when someone has been obliging enough to leave it on a train, and that doesn't happen very often, so we'll park this thought here for now. Anyway, the crucial thing you learn early on in Manifold Garden is that, even when an apple has been dropped and you can't move it, you can still use it.

Let's say you have a red apple and it's stuck to a red floor. You're now standing on a blue floor and holding a blue apple. Good news, you can use the red apple as a ledge to balance the blue apple on. Maybe that helps you get the blue apple where you eventually need it to be. Maybe it anchors it to the game's equivalent of a pressure plate and allows you to solve a puzzle. Maybe it simply teaches you something you need to understand in order to do something even more complicated.

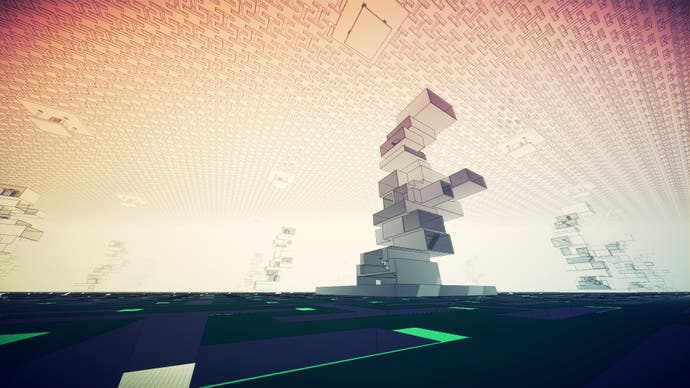

And yes, I have made all this sound complicated. This is a shame. Manifold Garden is complex, but it's not an elbowy jumble to play by any means. What it has is its own rules, and you need to learn these rules before you can do very much. Hence the slow opening as you trudge around corridors and bedsits, everything looking like a locked door or the coloured circuit that will open it. Welcome to the infinite void. How do you feel about being a locksmith, an electrician?

Stay the course! After a while the game opens up. You're suddenly outside, the architecture rising and the walls and staircases soaring around you. You start to understand that the worlds you're going through are not inhumanly vast, rather they are inhumanly repeated, and the repetition can be useful. Let's say you want to cross a gap. Run forward into space and the momentum will carry you slowly forward. You will fall for what feels like hours, your target platform zipping past again and again, but each time that platform's a little closer until you finally connect. Gap crossed. No fall damage. A thrilling moment, and the game just throws it at you with no pageantry because it has so much better in store.

Where did things truly click for me? They clicked when I emerged from a corridor and found myself on one side of a valley, stepped and crenellated up the wazoo in a way that made the whole thing look vaguely Central American. Or maybe I was suddenly an ant, trapped on the sheeny, intricate surface of a chunk of bismuth. What was opposite me? Another distant wall, stepped and crenellated, with a handful of its own little features repeating here and there. Was that me on the opposite wall, or was it where I needed to get? Solving this puzzle, man, it took me five minutes, but I was vibrating with sheer happiness for ten minutes at least once it was all done. Not because I had done something clever, but because I was in a world where unprecedented stuff was so willing to announce itself. What a place I was in!

Manifold Garden is full of this stuff. I can measure its greatness in the number of times I have taken my headphones off, rubbed my eyes, leaned back in my chair and found myself laughing at the audacity of what's going on in this game. I step away and I feel like a diver returning to the surface. I can measure its greatness in the number of times a colleague has passed by and looked at the screen and said, "Ouch, that hurts my eyes," or "What's actually going on there?"

Each passing level only adds to the brilliance. In one I must coax a ball through a maze by turning the maze and the world around the ball. In another, I must coax rivers across the ground, tipping them over the edge of the world, which wraps around and so the water falls from above shortly after it disappears into the depths below. In another, huge pieces of real-estate rise and fall, thudding to the ground around me completing circuits. Trees sprout, apples change colour, walls give way to glimpses of the infinite. The whole thing reminds me of a motel one minute and a plate glass university campus the next.

All of which sounds daunting. But in truth Manifold Garden's cleverest bit of cleverness lies in the fact that it's not daunting at all. It wants to let you explore without getting lost, it wants to give you the tools to experiment, and it wants to give you puzzles that yield to experimentation rather than busywork. It wants you to feel the elation of everything becoming clear. It wants you to know what it's like to solve a Rubik's Cube while you're inside the Rubik's Cube.

I love the mindset this game drops me into. The world outside the monitor vanishes. I am deep inside something intricate and wonderful, but also something strangely clear-headed and precise. My job is to turn the thing around and see how the parts work and interact and what potential there is for me while all these things are happening. There's something fiercely transporting about it all, but there's also a briskness that might just be the secret ingredient. You move so quickly through these worlds that the magic of the places you explore is not broken down and greyed out by the brain's habit of stripping everything back to puzzle pieces. I still think of certain areas I have visited: one had machinery in the center of a room, and two doorways next to each other in one wall, and each doorway, when I looked through it, took me to a different impossible elsewhere. But I moved in, pottered around, looped and riddled, and I solved the place before I had destroyed the thrill of it. As a result, it will be fresh in my head forever.

Manifold Garden took seven years to make, I gather. And I think in this game's topsy-turvy cosmogony you can actually see those seven years, time translated into space as if a big lump of the stuff had been squeezed through one of those pasta machines. You see the seven years of development in the horizon as it races out and repeats, showing you the void, and then showing you your own position again, echoed and echoed into the distance.

Have you ever really loved a building? A library, a train station, a museum? The thing about architecture is that even if you have the deeds, even if you have your own clothes in a closet somewhere, you can never really own it. It never feels like ownership anyway. Something about it is too big, too different, too magical to get your arms or your head around. This is where Manifold Garden lives. Play it. You will love it. And I really think it will stay with you.