Horace's incredible journey

How Die Hard Trilogy, a cancelled World Trade Center game and a small town in Kent led to this year's most overlooked masterpiece.

Where to start with a game like Horace? Maybe with how it's one of the year's finest games, and definitely its most overlooked. A sprawling, cinematic and ever-inventive 2D platformer - and puzzle game, and old-school arcade racer, and pixelart first-person shooter and about half a dozen other things it morphs into over its 20-hour running time - it's a lyrical flight of fancy that could only ever, really, have been made in the industrial town of Sittingbourne, Kent (or Shittingbourne, as it's affectionately known by locals).

Maybe it's best to start with Paul Helman, the developer behind the art, design, music, gameplay, writing and promotion of a project that's taken him some seven years to complete (with help from programmer Sean Scaplehorn). Horace is Helman, and Helman is Horace - a cauldron of pop-culture references and fondness for 16-bit classics, he's both classy and chaotic. At last weekend's EGX, his lanky frame hovered around the Horace stand dressed in an impeccable three-piece tweed suit and neatly polished tan brogues, all set off by a tatty Sainsbury's bag he kept constantly by his side. Here, in both Horace and in Helman, is a proper English eccentric.

Work began on Horace some seven years ago, though Helman's own story begins a little earlier than that; at the age of 17, he got his first job in the industry at Croydon-based Probe, working on some of its most high profile licensed games.

"When I went for my interview I was shown around the whole Probe office. I spent most of my time looking at Silicon Graphics machines and thinking this is the future," says Helman. "I was shown both the Alien Trilogy room and the Die Hard Trilogy room. In the Alien Trilogy room, all the blinds were shut, most of the lights were turned off and it was full of very goth people. It was very, very Alien.

"I had long hair at the time, but I've always been more on the punk side of alternative music. So I remember thinking 'Oh, this looks kind of cool I could fit in there,' and then I went around the Die Hard room and it was the exact opposite. And I can remember like, getting really good vibes at the interview and thinking this is really good because they asked me back for like a trial day and that was like, I hope I get to work on Alien Trilogy. Then I turned up and they said you're going to be working on Die Hard. I was like 'oh'."

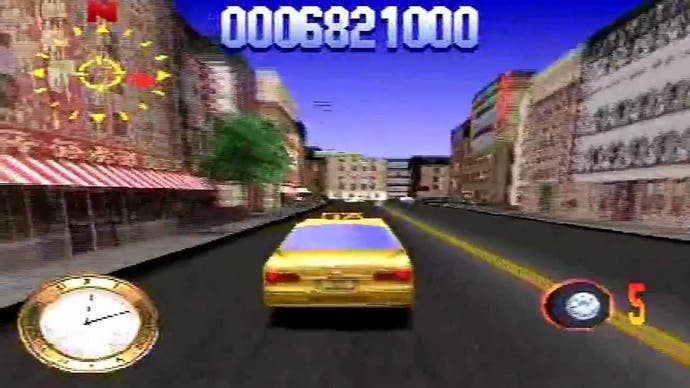

Die Hard Trilogy ended up being not a bad project to cut your teeth on, though; a portmanteau piece formed of three very different games taking on the first three films. Its final section, which reimagined Die Hard with a Vengeance as a mad sprint around Manhattan, also beat Grand Theft Auto to the punch when it came to urban open worlds.

"There was a point not long after I started where we presented it to Fox and Die Hard with a Vengeance was even more Grand Theft Auto-like - in that you could actually get out the car, run around and get into another car. We were going to have platforming sections. There's definitely a bit where you drove a forklift.

"So we showed it to Fox, and the trouble was we'd sort of made a small English town. They were like, you've read the script, right? This takes place literally in Manhattan. They were expecting skyscrapers and Harlem, and we're like oh okay... Luckily, they didn't cancel us on the spot - it wasn't too much work to rebuild a load of models."

Different times, of course. Even though Die Hard Trilogy was toying with some of Hollywood's most treasured IP at the time, the approval process was lax when compared to those of today. "It was great," says Paul. "Nobody really cared. A bloke whose name I can't remember turned up - the reason I can't remember is because everyone just called him Paul Cheese. It was something that sounded like Italian cheese. He would turn up and basically say, that doesn't look like America but that was about it. There was no style document from them or anything. I've since worked for Disney and other people - you get telephone directories from them for colour guides and the rest of that. That, though, was pretty much our only note - make it look more like America."

Die Hard Trilogy played fast and loose with its subject material - its take on Nakatomi Plaza, which imagined every floor of the tower block as a top-down arcade shooter, emerged simply because its coder was obsessed with RoboTron and wanted to make his version - but it worked. It didn't even need Bruce Willis' likeness to do its thing.

"That was quite funny as we were obviously using a lookalike," says Paul. "It's actually Dennis our lead coder. He looks nothing like Bruce Willis - he's completely wet shave bald, but I then drew various beards and hair on him. If you notice, Bruce Willis gets more and more bald throughout. One of the reasons we decided to do that and various other pisstakes was because we heard Fox were chasing him to get proper approval. He basically turned around and said that he wanted 50 per cent royalties. And we all laughed at the idea and luckily, Fox just told him where to go."

Willis of course ended up getting his face plastered over his own game, 1998's Apocalypse (a game which has its own fascinating story).

"We all think he did Apocalypse because he didn't get Die Hard. He then wanted his own face on something. Literally. Which was weird. Die Hard the film series is all right, but I can't help but think you could replace Bruce Willis with various other wisecracking action stars."

After the success of Die Hard Trilogy a sequel was greenlit by Fox, but by then the team had moved on - indeed, they'd moved on to form a new studio headed up by Simon Pick called Picturehouse.

"They were actually a subsidiary of Sony, but Sony didn't really give a shit about us. So we were contracted for three games. We made Terracon, which wasn't really marketed. The last game we worked on was then a version of Lemmings for the PS2 which they cancelled at 90 per cent done. We could have literally released what we'd done. It was a slightly more traditional Lemmings, but also in full 3D with like planes of movement and things like that. And then like, Lemmings that could travel through planes. It was a more traditional Lemmings puzzle type thing, but for the PS2.

"I think we made like 200 levels of stuff. Simon probably still has ISOs for it somewhere. But he's very cagey about it. Because obviously if that gets released into the wild it's not too hard to find out where that came from."

In-between Terracon and the cancelled Lemmings game was a more curious project - and another one that never saw the light of day, but for very understandable reasons.

"We worked on this game called Boom TV. The idea was It's a Knockout with explosives, with you blowing up famous landmarks around the world. You can see probably see where this is going - about a month before a literally world changing event I had just finished both making and animating the World Trade Centre exploding and collapsing."

Paul was working on Boom TV the morning of the terrorist attacks on September 11th, modelling Rio's Christ the Redeemer.

"We were a small team, obviously but we had two offices with just a bit of divider - and someone came in from the coding room basically saying a plane has flown into the World Trade Center. Me being the cynical idiot I was, went 'oh stupid pilots' and put my headphones on carried on working. And then I slowly realised that the whole of the rest of the office slowly syphoned off to watch like the start of World War 3."

Attempts were made to retool Boom TV, though it was soon cancelled. "It was actually really fun to play," Paul says.. "You had a choice of characters to play and essentially it was almost a shoot 'em-up where you throw bombs and you basically had to find places to pile bombs up. And then you get different types of bombs that would explode on impact to release other areas. The idea was that you would then plant all the bombs in the right place and then after a certain time limit they'd all go off and collapse - assuming you got everything in the right place everything would fall in one."

Picturehouse was a short-lived studio, and upon leaving a very different chapter in Paul's life began. "After our third game was done the contract up essentially so we were made redundant. I got paid a decent amount of redundancy, so I took a year off and did nothing. I was 25. It was amazing.

"I realised I could live for a grand a month. So I basically lived as cheaply as possible for as long as possible. I mean, strictly speaking, I took a bit of freelance work. I didn't even really start properly working for 18 months, two years. I just had enough of games at the time and I was considering anything else to do with art. I'm massively underqualified. I left school at 16 and basically just got an A in art."

There were various freelance gigs, but what exactly happened in the period between a full-time job and starting on his own passion project? I joke that it must have been spent dossing around Sittingbourne, getting stoned and playing video games. It's not too far off the mark.

"Well, it's all been a bit fuzzy and hazy. You say sitting around getting stoned and playing video games? That's kind of all I did for like 10 years until I started Horace."

Play Horace and it shows, in the best possible way. It's a bundle of references from the worlds of music, of cinema and of games that all coalesce in one brilliant whole. It's no surprise to discover that Paul's something of a hoarder - in his house in Sittingbourne are various instruments (he's an accomplished drum player, amongst other things) and a bedroom that's a dense library of pop culture.

"I'm one of those horrible nerds. My bedroom is fifteen by twelve and every wall has shelves from the floor to the ceiling. I've got two, two and a half thousand CDs, a thousand DVDs, about a thousand VHS tapes and a similar amount of wall space that's video games."

It's a collection that's mightily impressive, and reaches great depths. When well-known UK punk outfit Snuff wanted to reissue their first album, they realised they'd lost the original masters - so they then turned to Paul who had one of the few remaining original copies to master from.

"The thing is, I've always been a massive nerd and I've always collected stuff, because I don't really do much else. So I always spend my money on buying stuff. So I've got both Japanese and American versions of Final Fantasy 6. I bought all these sorts of things like in the 90s when eBay started. In the early 2000s I bought all four Mega Drive Phantasy Stars for about 30 quid including postage - half of that was the postage from Japan."

It's all helped provide the healthy love of classic games that informs so much of Horace. "I basically gave up with modern games. And it was brilliant because it basically gave me a chance to play Final Fantasy 6, Earthbound. All the best games ever that no one talks about as much these days. I can't remember who said it but there's the famous games quote of nothing ages worse than cutting edge graphics. The Last of Us Remastered looks incredible, but give it five years and everyone will be like, that's a bit weird looking."

Horace is Paul's opus, a pixelart epic. "I wanted to make a arty platformer that expanded like a Final Fantasy," he says. Its story is lifted from 1979 Peter Sellers vehicle Being There (which I admit I haven't seen just yet - though Paul was gracious enough to give me a copy when we met again at EGX). It's a gently satirical tale of a robot being reunited with his family and finding himself elevated to strange places, and it's a deeply touching tale too.

"I'm surprised how emotional it's been for some people. I've seen streamers crying, and I was like okay... I wanted it to be very filmic. Games often just pick a genre and stick to it. Grand Theft Auto is gritty crime, Mario is a whacky cartoon. And I was like, why? Why does it have to be one or the other? Let's just grab everything and put it all together. That's kind of my ethos.

It's an ethos that makes Horace dizzying to play - this is a platform that constantly wrongfoots you over its extended running time, sort of like Nier Automata in a bowler hat. "One of the last main big beats towards the end is when you play all the mini-games at the robotworld tournament.. And I basically wanted a reason to have all the mini-games in there - our producer wanted to push that even further, so they're all slightly different versions of the ones you come across in the main game. The last one is a mini-game that you don't get to play anywhere else. And that's 20 hours into the game."

Playing Horace, you can tell that this is a game that took some seven years to bring together. Was it always the plan for it to take so long, though? "I had no idea - I was happy to work for as long as it took. At the time I was still taking freelance contracts. I worked for three years. And I essentially got the first ten per cent together, and working really brilliantly, and not to put a massive dampener on everything, but unfortunately, my mum died. And I just threw myself into it for a few months.

Programmer Sean Scaplehorn was brought on board, helping Paul put together a demo for a London conference where it caught the attention of a handful of publishers. "505 did a deal to pick it up. Basically, though, they gave us a producer and left us alone for four years."

The hands-off approach seemed to have worked out - especially for some of the lawyer-baiting sections of Horace that play fast and loose with well-known IP. "I'm convinced that 505, apart from the producer, didn't really play the game. There's one mini-game that's really early - it's Ghostbusters meets Pac-Man, and to make [producer] Dean laugh I wrote a quick piece of music that riffs on Pac-Man doing Ghostbusters."

It also makes for a game that feels uniquely personal. Sittingbourne itself stars throughout - though never explicitly, though if you've ever had the fortune (or misfortune) to visit you'll find plenty that's familiar. There's also characters drawn from friends and family, and the sense that Horace offers an insight into Paul Helman, albeit through a pixelart filter.

The hands-off approach, though, has meant that Horace has struggled to find traction, with little by way of reviews or support. To play Horace is to fall in love with it, but it's clear that not enough people have played it. "It's a relief that it's out and people like it. I wish it had sold more, though obviously we're still ongoing with consoles and stuff."

The console question is ongoing, though hopefully there'll be more concrete news to share in the near future. Horace was made in Unity with the intention to port it to other platforms, and it's something that Paul is certainly keen to do. What happens after that, though?

"I've got a couple of ideas for some other games. One of them's reasonably simple - I want to make a game essentially for blind people, but that anyone can play. Just so I don't have to draw anymore graphics. I then have an idea which I've had for decades - it was my initial idea, but I realised it'd be far too complicated. Horace was my simple idea..."

So after all that, was Horace worth the seven years of toil and isolation? "Oh yeah. I think it's been good. I think 505 leaving me alone allowed me to do what I wanted. It makes me laugh - unsurprisingly I ended up paying attention to negative comments more than I do others, and the amount of people, well most people seem to love it, but some people are like you can't do this in a platform game. You can't have three hours of cutscenes. And I'm like, why not? Who said a platformer has to be presented like Mario. Maybe it's all just my hatred of authority."

Still, I'm delighted that 505 allowed something like this to exist. Horace is a work of mad beauty, uniquely British, genuinely touching and fluent in the language of video games. It's funny that Helman now shares a publisher with Hideo Kojima now that the Japanese developer's Death Stranding is heading to PC - because, for my money, Paul Helman is the real auteur. I've one last question, though. How, in those seven years of toil, did Paul keep himself sane?

"Oh, I didn't," he says with a smile. "I'm absolutely batshit."