On the strange promise of a board game with a few missing pieces

Under the sofa.

It was never Professor Plum in our house. The professor was entirely innocent. He was in the clear. Perfect alibi. Water tight. He was doomed for eternity to be one of the good guys.

I don't know when we lost the card for Professor Plum, but it changed the way we all thought about him. With no Plum card in the deck to start with, he simply couldn't end up in the murder envelope. He couldn't have done the crime! But we still had the counter, so Plum was still physically there in the house when it was time to investigate. This situation gave him a kind of purity. Everyone else was under suspicion, but Plum? Plum was always on the side of the angels.

When I bought my own Cluedo set a few years back, I immediately ditched the Professor Plum card it came with so that the experience would mirror my experience of playing the game as a kid. Five children in my house growing up, and all of us clumsy and careless. As a result, we played Scrabble with missing vowels, we played Monopoly with limited liquidity. We played a version of Cluedo in which it was never Professor Plum - in which it would never be Professor Plum.

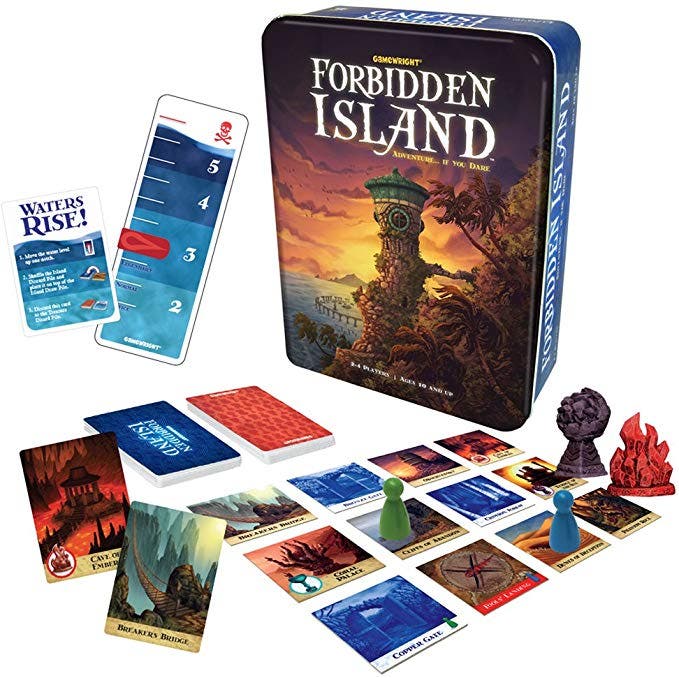

I thought of Plum this Christmas. Not because Cluedo was on the cards, but because I was doing a spot of tidying up and I found a box in which, in amongst loose pens and bits of wool, the tin for Forbidden Island had upended itself. Forbidden Island is a really beautiful board game - a co-operative affair in which you hunt for various treasures on an island that's steadily sinking. It's clever and spiteful and filled with opportunities for your own behaviour to unsettle things for you. But what I love most about it is that tin it comes in - I simply love the chummy rattle of cherished things inside a tin - and I love the four treasures you're after in the game, each of which are delivered as little chunks of plastic sculpture. Speak their names with me! The Earth Stone, the Crystal of Fire, the Statue of the Wind, and the Ocean Chalice.

Oh, the Chalice. Long story short, as I got the island back into the tin, I tracked down all the cards and counters and various bits of business, all of it except for one thing. The Ocean Chalice was missing. The Chalice! A lovely piece - a cool blue, a long stem, the whole thing perfectly proportioned. There's a little resting spot for it in the tin, and it felt rather sad looking in there and seeing four treasures spaces, one of them empty. My count of enchanted objects was literally diminished by one.

As this was Christmas - and as every Christmas I end up doing something like this - I raced through the house for hours looking for that chalice. Inevitably, it was under a sofa. As soon as I found it, though, I sort of wished I hadn't. The appeal of a game like Forbidden Island is ancient mystery, right? A wind through the chimes, a shudder disturbing matted veils of spider-webbing. The sense of dark absences down there in the murk. Maybe a box containing three of the four great treasures would be kind of perfect in its imperfection? Maybe there would be fun to be had from the Chalice's storied absence, just as Cluedo was always more fun when there was a single definite goody doing the rounds of the stricken manor house. I feared for Plum, locked in that house with a murderer.

What I'm getting at, I guess, is that I am starting to see unique opportunity in the fact that you can lose bits of board games. This opportunity is unique to board games, because it is unique to the physical world where board games live. I could play some digital version of Cluedo until the sun explodes and I would never be able to lose Professor Plum. I could play the iOS Forbidden Island and the Chalice would always be there for the taking each time.

I've always understood the idea of house rules with board games - this special kind of flexibility that games have when you're all sitting around, when there's no code acting as gatekeeper to the fun, and you can all, together, decide to store any forfeited money in the middle of the Monopoly board and give it to the first person to land on Free Parking. But it took me a lot longer to discover that lots of limitations in board games are there for a reason. It took until Pandemic, in fact, which was the first game where I realised - oh, I can just look at the remaining cards or cubes and literally see how much of a chance we have of winning. And then I went back to Monopoly and discovered that there are 32 houses and 12 hotels for a reason, and the reason is balance. The reason is that the designer wanted you to have to race to build, and wanted you to run out of chances to build if you weren't quick enough.

So what happens to games where the physical amounts of things take a beating? Where fate intervenes and things go missing? When nobody can buy Fenchurch Street, because Fenchurch Street the card went up the vacuum twelve years ago, although the spot on the board remains? What happens when one of the Risk objectives is lost for good but lingers on in the memory as a sort of phantom limb?

Legacy games do this to some degree. You play a game and follow the instruction and rip up a card or wipe something off the board for good when you're told to. The game ages over time in a way that has been entirely planned out. But I love the idea of letting entropy be the guide, too. Are there other versions of Cluedo waiting in there, waiting to be unlocked by certain pieces going under the sofa? Is there a best version of Scrabble where time has eaten away all but a handful of consonants?

And it makes me think. Every now and then I head to eBay and linger over HeroQuest, a game I loved as an eleven-year-old but never owned. For years I've assumed that I wanted a complete set, all the pieces and bits and bobs. But a complete set costs money. Maybe what I'm after is one of the incompletes. A unique HeroQuest! Maybe there is fun to be had in the restrictions that missing pieces bring. Maybe there is fun to be had in the empty spaces.